The life of a startup

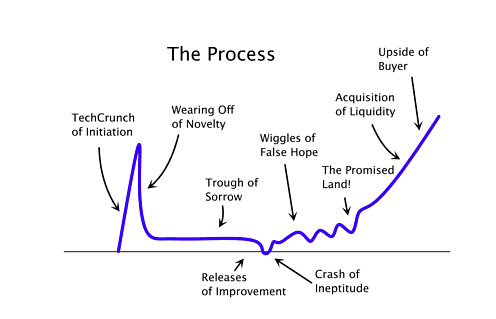

A few years back at a YCombinator dinner, Paul Graham and the other partners drew a great diagram depicting the life of a new product. The main discussion is here: http://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=173261. It captures a viscerally truthful thing about the life of a new company- first you’re excited, then you’re not, and if you stick with it, you just might make it work. It could take years. But you may fail too, you never know until you do it.

The Question

The big thing is, while you’re in the Trough of Sorrow is, what do you do? How do you beat it?

Traditional business literature won’t help you solve it- most of that stuff is focused on life after product/market fit, after the Trough of Sorrow. A lot of startup stuff is focused on the initial phases, when you don’t have a team, idea, or investors.

What happens when you have a team, an idea, and investors, but it’s not quite working yet? What do you do there?

How to beat the Trough of Sorrow

I have some notes from my personal experience, and from others who have beat the Trough of Sorrow, and wanted to share them. First off, there’s both an emotional component as well as an analytical one.

Dealing with the emotions

Let’s start with the emotional first. First, a couple important things to remember:

- Getting to product/market fit is hard, and even though you feel like you’re uniquely failing, you’re actually not. Turns out every startup has to go through this, but not every startup survives it. Entrepreneurs will blame themselves for failing, but it’s OK, this is hard and we all start the journey by failing a lot.

- A corollary to the above is, expect to face the Trough of Sorrow. It’s hard to avoid. Quitting, starting over, executing a “too big” pivot, and other avoidance strategies won’t keep you from hitting a difficult point again, it’ll just delay the inevitable. Instead, just figure out how to work through it.

- Expect to fight with your cofounders. When things are going great, cofounders tend to go along since the focus will be on keeping the momentum up. When things are mixed or going badly, there will be meaningful disagreements about what to do next

- Quitting is your decision. There’s a huge spectrum of tools you can use to fix up a broken thing. You can change the product, switch customer segments. You can recapitalize the company, reset the team, and fire your cofounders. You can (usually) find a way to keep going if you want to. Whether or not you want to quit, that’s up to you, but don’t think that quitting and starting a new thing will let you start something up without passing through this difficult phase

- Churning customers, employees, and cofounders isn’t failing. While you’re going from one iteration to the next, people will fall off the wagon. It just happens. That’s OK! That’s part of what happens, and even though it’ll feel like it’s a failure, don’t let it discourage you. The question is, does the new strategy make more sense than the old one? You only fail when you fail.

An additional thought on quitting: It’s ultimately the entrepreneur’s personal decision to quit, because there’s always some alternative scenario, as unpleasant as it might be. You can always dilute yourself more, raise more capital, or reduce the burn rate. It can add more time to the clock, which might be unpleasant, yet it might save the company. Is it always logical to do that? Maybe, and maybe not! But it’s worth considering that there’s always another move, and an entrepreneur shouldn’t ever feel like they’re somehow “forced” to quit.

A lot of entrepreneurs quit when they hit the Trough of Sorrow, struggle for 12-24 months, and face up to the reality that they’ll have to raise another dilutive round. Is this a good time to quit? Maybe. But given that the majority of startups go through this kind of stage, I’d actually argue that it’s just part of struggle to being successful. Sometimes it just takes 3 years to get through the Trough of Sorrow, but on the other side is something that might really be worth the pain. Maybe :)

I find that when I spend time with startups as an investor/advisor, a lot of my time ends up being about the above issues. Probably 80%, actually. If you can minimize the emotionality of feeling like you’re failing, you can try to keep the team together and get to the problem solving part.

Dealing with the problems

If you can hold everything together, and keep the team productive enough and the runway long enough to try to make a run at the problem, then here’s a few wild unfounded generalities on how to proceed. It’s super hard to generalize here but here’s an attempt.

- Identify the root problem. Is the product working? Does the onboarding suck? Or is execution on growth lacking? You can figure out the main bottleneck by trying to understand where it’s working and where it’s not. If the problem is high retention and high engagement, but not a lot of people are showing up, just focus on marketing. If the product is low retention and low engagement, you probably have to work on the product. More marketing and optimizing your notifications won’t help there

- I find that much of the time, startups take too much product risk, and that’s why they aren’t working. Most of the new products I run into aren’t at the phase of “we’re product/market fit, just add more users!” Instead, most of the time, the products are just fundamentally broken. They are asking users to do new things, they exist in new markets with no competitors, and as a result, it’s unclear if the customer behavior is there to support their product. Instead, try to take a known working category and try to invent 20% of it, rather than 90%. Apple didn’t invent the smartphone, the MP3 player, or the computer, and yet they are super innovative and successful. You don’t have to invent a new product category either, and it’s easier to get to product/market fit when you have a baseline competitor to compete against.

- Resist the urge to start over. There’s always a feeling that if you just rebooted, you’ll somehow avoid the Trough of Sorrow. Not true. Trust your initial instincts in your market and in your product, and figure out how to guide it into a similar place. If smart people invested in you and in the market, there’s probably something there, but you have to find it.

- Get your product to be stripped down, focused, and so easy to understand that it’s boring. Look, you’re not in this to impress your designery friends, you’re in this to communicate your product’s value prop in simple and focused terms. The closer you are to that, the more boring your product will sound- that’s a good thing!

- Money buys time, and time buys product iterations. This is why there’s a school of thought that says, raise as much money as you can at every point- before product/market fit, raise the max amount so that you have as many iterations as possible to ensure you get to P/M fit. After P/M fit, raise as much money to maximize the upside. Something a few steps back from that extreme is probably the right one :)

- Pick up small tactical wins. Even if you do something in the product that doesn’t scale at first, it can be worth it- like prepopulating content, inviting all your friends, doing PR, etc. These small wins build momentum, raise team morale, gets you incremental amounts of capital, and makes it so that you can keep going. Over time, to scale, you can figure out how to systematize these processes or they can end up bootstrapping bigger and more scalable ideas.

- Small teams are great. They move faster, way faster. If you plan to do lots of product iterations, you don’t need to communicate all the changes and get buy-in from everyone. Conversely big teams have lots of chaos every time there’s a bit pivot. Build out the team afterwards to create the complete featureset, but until then, consumer product teams can just be a few engineers/designers and the product leader. That’s <6 people.

I could write lots more here, but I’ll save some thoughts for next time :)

Finally, I wanted to quickly reference a step-by-step roadmap I wrote a year back with some more thoughts on getting to product/market fit, which you can see here: http://andrewchen.co/2011/05/22/2011-blogging-roadmap-zero-to-productmarket-fit/