[Andrew: Paid marketing remains an integral part of many products’ acquisition channels, and one of the key metrics is Cost of Customer Acquisition, which is a nuanced calculation with lots of gotchas. My good friend Brian Balfour (ex-vp growth at Hubspot) put together this incredible essays with details on how to think about it.]

Brian Balfour (ex-VP Growth at Hubspot):

Note: This is a big topic that’s best addressed with live examples and interactive frameworks. To that end, I’ve included a number of examples of real companies, plus interactive spreadsheets that you can access throughout the guide. To adapt any spreadsheet for your own calculations, click here, then go to File > Make a copy to create your own version.

Customer acquisition is not CPA – Three examples

To start off, let’s address a common myth. Customer acquisition cost (CAC) and cost per acquisition (CPA) are commonly conflated, and yet in reality they’re completely different metrics. Understanding the difference is the start to understanding CAC in depth.

CAC specifically measures the cost to acquire a customer. Conversely, CPA (Cost Per Acquisition) measures the cost to acquire something that is not a customer — for example, a registration, activated user, trial, or a lead. The two are related because CPA is usually used to measure the cost of things that are leading indicators to CAC.

Four examples of how CAC and CPA are different but related:

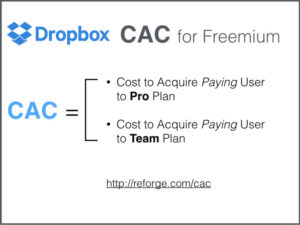

1. Dropbox

Since Dropbox is a freemium product, CAC would be the cost to acquire a paying user on either their pro or their team plan. CPA would be used for things such as the Cost Per Registration (of a free user), Cost Per Activated (free) User, and other important, but still non-paying, actions that signal that someone has moved from being a visitor to a user of the product.

2. HubSpot

Since HubSpot is a B2B SaaS product, CAC would equal the cost to acquire a new customer on one of their Basic, Pro, or Enterprise plans. CPA would be used for leading indicators to CAC, such as Cost Per Lead, Cost Per Sales Qualified Lead, Cost Per Trial or other points in the marketing and sales funnel.

3. Facebook

B2C companies supported by ad models are a little different. In Facebook’s case the paying customer are advertisers so CAC is the cost to acquire a new advertiser. However if you just look at users, users/customers are the same. CPA is most likely used for things like Cost Per Registration, Cost Per Activated User, etc.

The key point is the first thing you need to do to understand CAC is very simple:

Define who/what a customer is in your model.

Make that definition clear and simple and get the language between CAC and CPA consistent otherwise communication will be very confusing.

Get new updates, usually once a week – featuring long-form essays with what’s going on in tech.

The basic calculation of CAC and why it’s wrong

If you google ‘how to calculate cost of customer acquisition” you will get the basic formula below:

CAC = Total Marketing + Sales Expenses / # of New Customers Acquired

On the surface this is correct, but it is missing a lot of details and definitions around each variable in the equation to get it right. Even the best basic calculation can be very misleading. For example, using this formula you might look at the below spreadsheet and assume the following:

To adapt this spreadsheet for your own calculations, click here, then go to File > Make a copy to create your own version.

But what if I told you the following things:

- It takes on average for most customers 60 days from lead to become a customer.

- Not all customers are new customers, but some of them are returning.

- This is a freemium product and there are costs to supporting users while they are free before they become a paying user (customer).

These three tidbits of additional information should change how we look at the basic formula above. Instead of taking the equation at face value, we need to evaluate a few questions first.

How to really calculate CAC

There are three key questions we need to ask to define a more accurate calculation of CAC for a business. All of them dig into a level deeper around the variables in the equation.

Key Question #1: How long between your marketing/sales touch points and when someone becomes a customer?

The first issue with the basic calculation is that it doesn’t take into account the time period between when you spend the marketing/sales money and when you actually acquire a customer. Here are two examples:

Example 1: Freemium Product

Let’s look at Dropbox as an example. When you sign up for Dropbox you start using their free tier. You use Dropbox free for some time period until you hit your storage space limit, which you then might upgrade. For a lot of users that time period is months (and in some cases over a year). The story is the same with other freemium products such as Evernote, Buffer, etc.

Example 2: SaaS Company w/ Inside Sales

Most SaaS companies with inside sales models someone might become a lead this month (due to our marketing efforts this month) but will take 60+ days before they become an actual customer because they need to go through the sales process.

If you don’t take these time periods into account, you could be overestimating or underestimating CAC and as a result making some terrible operating decisions.

Here is an example of how you could overestimate.In the below example, CAC is being calculated by taking the month’s marketing costs and dividing it by new customers in the same month.

To adapt this spreadsheet for your own calculations, click here, then go to File > Make a copy to create your own version.

In March we try some new channels which causes a large increase in marketing costs. Under the simple calculation our CAC is $148. If our target CAC is $125, we would likely make the decision that March was unsuccessful and we would turn off those new channels.

But, let’s say it actually takes 2 months for someone to become a customer. Below is the same data but changing the calculation to account for this 2 month period.

To adapt this spreadsheet for your own calculations, click here, then go to File > Make a copy to create your own version.

This change tells a completely different story. In March we have a CAC of $84, and in April a CAC of $111. Instead of turning off the new channels we tried in March, we would probably make the decision to scale them.

The key question about time between marketing/sales expenses and acquiring a customer does not matter if you fall in one of two scenarios:

1. The time between marketing touch point and someone becoming a customer is very short. This is true for a lot of B2C companies that have very short decision funnels for users: Snapchat, Instagram, and others.

2. Your marketing/sales expenses are so consistent that it normalizes itself out over time. But even in this case it is best to be more accurate.

You need to figure out how the timing of the expenses correlate with the timing someone actually becomes a customer. Marketing expenses could correlate differently than sales expenses.

The simplest way to account for this is figure out your average marketing/sales cycle. In other words what is the average amount of time from first marketing touch point, to acquiring the customer?

Here’s an example. Let’s say we are a SaaS company where the average time is 60 days from lead to customer and we believe the sales expenses are spread evenly over that two month time period.

The CAC equation would be as follows:

CAC = (Marketing Expenses (n-60) + 1/2 Sales (n-30) + ½ Sales (n)) / New Customers (n)

n= Current Month

Here is an example model with that calculation built in:

To adapt this spreadsheet for your own calculations, click here, then go to File > Make a copy to create your own version.

Key Question #2: What expenses do you include in the Marketing + Sales?

The second question you need to answer to get an accurate CAC calculation is what expenses do you include in the numerator (marketing/sales)? Before we look at some examples of the answer to this question differs, here are the three most common mistakes I see:

Mistake #1: Not Including Salaries

You need to include the salaries of all people working on marketing and sales. We see CAC numbers a lot where they aren’t included. This includes not just the individual contributors who are 100% dedicated to marketing/sales, but also those (often times managers) who spend part of their time on marketing/sales. A CAC number with salaries included is often referred to as “Fully Loaded CAC.” There are some scenarios where it is useful to separate Fully Loaded from Non-Loaded CAC which we’ll explain later.

Mistake #2: Not Including Overhead

Similar to the mistake of not including salaries, you need to include the overhead (rent, equipment, etc) allocated to those employees working on marketing sales.

Mistake #3: Not Including Money Spent On Tools

The marketing and sales tool space has exploded. Most teams are using 10+ tools to operate their marketing and sales machine. These tools can add up in cost and need to be included in the expenses of your CAC calculation.

If you include those main things, the answer to this question starts to get a little more complicated and range from company to company. A couple of examples:

Spotify and the Case of Freemium – Does that Include Product/Engineering/Support?

Spotify is a freemium business. They have millions of users using the free version of their product which helps them acquire new users through sharing music and other viral channels.

In most companies, product, engineering, and support are not included in CAC (typically part of R&D). But if the free product is your primary method of customer acquisition, shouldn’t the expenses that support that free product be included in the expenses portion of your CAC calculation? There are different opinions to this question, but we fall on the side of yes.

If you had engineers, PMs, and other roles on the marketing or sales team for marketing/ops you would include those salaries and expenses in the CAC calculation. The engineers, PMs, or other roles might not technically be on the “marketing” or “sales” teams, but they are still expenses that are required to support new customer acquisition.

HubSpot and the Case of SaaS – Include Customer Success Costs?

Most SaaS companies like HubSpot have sizable Customer Success teams. The definition and roles of these teams can vary widely. Some Customer Success teams are purely devoted to churn prevention. Some are devoted to helping onboard a new customer. Some are devoted to winning previous lost customers back.

All this begs the question, should customer success costs be included in CAC? Some of these responsibilities touch acquiring new customers and therefore make the case that they should be allocated to CAC.

Dollar Shave Club and the Case of Subscription Ecommerce – Support, Shipping for Free Trial?

Dollar Shave Club is a subscription ecommerce business. They famously have a one month trial for $1. That one month trial has a number of expenses outside of marketing, including shipment costs for the initial package, support during the trial, and other costs. Should those costs be included in CAC? The answer to that depends how you define a new customer.

In Dollar Shave Club’s case, we would make an argument that someone on a $1 trial is not a customer yet. A new customer is someone that extends beyond the trial. Therefore all of those costs associated with supporting the free trial should be included in CAC. Those costs are partially offset by the $1 trial payment, but not fully offset.

A customer is a customer, right? Not necessarily. When it comes to calculating CAC, we need to distinguish between new and returning customers. In most organizations there are marketing and sales efforts focused on new customers, and there are marketing and sales efforts focused on retaining or getting customers back.

The mistake is only including marketing and sales expenses in the numerator for new customers, but including all customers (including returning customers) in the denominator. This will make your CAC look artificially low. You can solve this in one of two ways:

1. Include all marketing/sales expenses (including those focused on retention) and all customers.

2. Separate expenses for new customers from reactivating old customers and separate out new from reactivated customers in the denominator.

Recap

From the examples we’ve covered today, I hope it’s more clear that calculating true CAC involves a lot more than a simple, one-size-fits-all equation.

Instead, an honest assessment of customer acquisition cost looks at the length of your sales cycle, how many customers are truly new customers (as opposed to returning customers), and the total costs and resources required to support marketing efforts that lead to new customer acquisition.

Brian Balfour is CEO of Reforge, previously VP Growth @ HubSpot, EIR @ Trinity Ventures, Co-Founder of Boundless, Co-Founder of Viximo, Co-Founder reCatalyze & PopSignal.