Hi readers,

Consumer startups have gone through many phases: Web 2.0, Facebook apps, Mobile (remember SoLoMo?), and in recent years, some of the best opportunities have been happening in the real world. In recent years, the Gig Economy has taken over. Startups like Uber, Airbnb, Instacart, and others have been able to find product/market fit and scale their businesses.

But what’s the next? The essay below argues: “The Passion Economy.” And my a16z colleague Li Jin unpacks this idea more thoroughly.

(And quick plug, if you want to read more essays like this — this article was originally posted on a16z.com and you can subscribe to the newsletter here)

The Passion Economy theme unifies a number of themes that we at a16z have been working on:

- Reinventing the service economy. We’ve written about this here. There will be many new software platforms that allow creators/influencers/service providers to work on what they love and earn income from that work

- Easy-to-use tools. Within the platform, there are deep SaaS tools that help people in the Passion Economy actually do their work — particularly key when the work is purely digital in nature, like video streaming or audio broadcasting

- Massive distribution. People need to get found — both by their customers and their audience — and we now can plug into platforms with billions of consumers. Platforms will need to provide marketplace-like features that lean transactional, or more like an ongoing subscription relationship

- Pragmatic education/training. College aren’t built to teach the skills for the Passion Economy, and people will instead turn to online schools/programs/training for lifelong learning in the ever-changing ecosystem

- Every startup is a Fintech. Fintech services that help facilitate both business and personal needs — whether that’s creative financing options, solopreneur banking services, or working capital

If this resonates, it’s because this is a list of the massive trends that are reinventing the way we work. As a society, we are right in the thick of this movement — but it’s helpful to give it a distinct name, although you might argue startups like Udemy, Patreon, Shopify, Substack, and many others have already been blazing this path.

I love this trend as someone who has worked deeply both in the passion economy — writing this blog combined with investing/advising startups — and also in a more traditional role in the gig economy at Uber. We’re seeing a lot of activity across the entire market and it feels like a meaningful addition to add both opportunities for Gig Economy and the Passion Economy together.

Thanks,

Andrew

The Passion Economy and the Future of Work, by Li Jin

The top-earning writer on the paid newsletter platform Substack earns more than $500,000 a year from reader subscriptions. The top content creator on Podia, a platform for video courses and digital memberships, makes more than $100,000 a month. And teachers across the US are bringing in thousands of dollars a month teaching live, virtual classes on Outschool and Juni Learning.

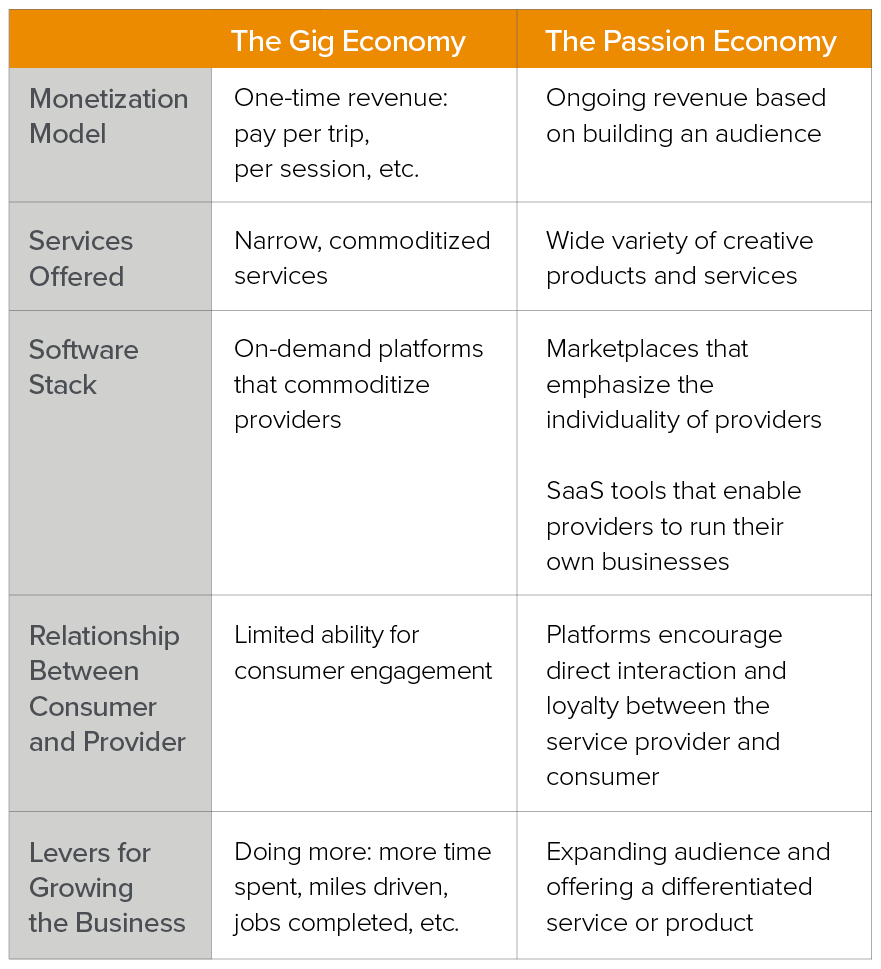

These stories are indicative of a larger trend: call it the “creator stack” or the “enterprization of consumer.” Whereas previously, the biggest online labor marketplaces flattened the individuality of workers, new platforms allow anyone to monetize unique skills. Gig work isn’t going anywhere—but there are now more ways to capitalize on creativity. Users can now build audiences at scale and turn their passions into livelihoods, whether that’s playing video games or producing video content. This has huge implications for entrepreneurship and what we’ll think of as a “job” in the future.

The Evolution of The Passion Economy

In the past decade, on-demand marketplaces in the “Uber for X” era established turnkey ways for people to make money. Workers could easily monetize their time in specific, narrow services like food delivery, parking, or transportation. These marketplaces automated the matching of supply and demand, as well as pricing, to enhance liquidity. The platforms were convenient for both the user and the provider: since they took care of traditional business hurdles like customer acquisition and pricing, they allowed the worker to focus solely on the service rendered.

But though these platforms provided a path to self-employment for millions of people, they also homogenized the variety between service workers, prioritizing consistency and efficiency. While the promise was “Be your own boss,” the work was often one-dimensional.

Monetizing Individuality

New digital platforms enable people to earn a livelihood in a way that highlights their individuality. These platforms give providers greater ability to build customer relationships, increased support in growing their businesses, and better tools for differentiating themselves from the competition. In the process, they’re fueling a new model of internet-powered entrepreneurship.

It’s akin to the dynamic between Amazon—the standardized, mass-produced monolith—and the indie-focused Shopify, which allows users to form direct relationships with customers. That shift is already evident in marketplaces for physical products; it’s now extending into services.

These new platforms share a few commonalities:

- They’re accessible to everyone, not only existing businesses and professionals

- They view individuality as a feature, not a bug

- They focus on digital products and virtual services

- They provide holistic tools to grow and operate a business

- They open doors to new forms of work

1. They’re accessible to everyone, not only existing businesses and professionals

New consumer products are making it easy for anyone to become an entrepreneur. In the mid-2010s, the rise of the influencer industry allowed top-tier creators to monetize through advertising. These platforms expanded to support a broader range of money-making activities, from manufacturing physical products (e.g. Vybes, Hipdot, Genflow) to creating personalized videos (Cameo, VIPVR, Celeb VM).

Now the ability to make a living off creative skills has trickled down to individuals at scale, helping everyday people to launch and grow businesses. Previously, only established businesses could access software engineering talent to build websites or apps; now, no-code website and app builders like Webflow and Glide have democratized that ability. Startups are also building mobile-first, lightweight versions of incumbent desktop software: Kapwing, for instance, is a web and mobile editor for videos, GIFs, and images that aims to displace legacy creative software.

Companies have the opportunity to engage entrepreneurs in the early stages, then capture economic value as they grow. They might start with a very basic offering and add product capabilities as their customers earn revenue and develop new needs.

2. They view individuality as a feature, not a bug

Whereas previous services marketplaces were rigidly built for standardized jobs, new platforms highlight variation among workers in categories that can benefit from more diversity in user choice.

Take Outschool, an online marketplace for live video classes in which teachers are predominantly former school teachers and stay-at-home parents. On the platform, instructors can develop their own curricula or browse lists of courses requested by users. Beyond the subject matter, the marketplace’s UI emphasizes each teacher’s background, experience, and self-description. Parents and students can message instructors directly.

Above: Outschool lets teachers sign up to teach engaging video sessions to kids

For new platforms, this model can pose a sizeable risk: once consumers are able to work directly with a preferred provider on an ongoing basis, they may take that relationship offline. Marketplaces can combat disintermediation by offering workflow tools, like scheduling and invoicing, and by building in additional incentives that make it worthwhile for providers and users to remain on-platform. Marketplaces that cultivate these direct relationships can also succeed by focusing on areas—like education and tutoring—in which consumers might have repeated matching needs with a variety of different providers over time.

3. They focus on digital products and virtual services

Whereas past generations of entrepreneurship-enabling platforms typically focused on selling physical products (e.g. Amazon, Etsy, Ebay, Shopify) or in-person services (e.g. Taskrabbit, Care.com, Uber), new creator platforms are focused on digital products. A platform built specifically for packaging and selling digital products looks different than a platform that is built for tangible goods.

Podia, Teachable, and Thinkific are all SaaS platforms that allow creators to make and sell video courses and digital memberships. Previously, these types of “knowledge influencers” had to either conduct classes in-person (restricting them to local customers); jerry-rig platforms meant for physical products, like Shopify; or customize sites like Wix and Squarespace. New platforms capitalize on the idea that expertise has economic value beyond a local, in-person audience.

Above: Thinkific lets you create, market, and sell online courses

On the interior design marketplace Havenly, designers work remotely and interact with clients entirely online. For designers, the benefit is a steady stream of clients without the heavy lifting—since Havenly takes care of marketing—and the flexibility to work whenever, wherever. For clients, the benefit is access to a service that would otherwise be expensive or inaccessible.

4. They provide holistic tools to grow and operate a business

Unlike discovery-focused marketplaces, which monetize through advertising, membership fees, or cost-per-lead, new platforms in the creator stack are often monetized through SaaS fees that increase as customers grow. Others take a percentage of the creator’s earnings. This means that platforms are incentivized to help creators succeed and grow, rather than driving discrete, one-time transactions.

Some platforms offer marketing tools like custom landing pages, coupons, and affiliate programs. Others provide behind-the-scenes support: Walden, for instance, connects new entrepreneurs with coaches for strategy and accountability.

Sometimes, support may be bundled into platforms that help providers start a business. For instance, Prenda—a managed marketplace of K-8 microschools—provides teachers (called Guides) with curricula, computers, software, supplies, and assistance in navigating the necessary regulatory requirements and insurance.

5. They open doors to new forms of work entirely

New digital platforms enable forms of work we’ve never seen before:

For a more extensive model of how human capital can give rise to new industries, look to China. On the microblogging site Weibo, for instance, users sell content such as Q&As, exclusive chat groups, and invite-only live streams through memberships or a la carte purchases. This has spawned a wave of non-traditional influencers—financial advisors, bloggers, and professors—beyond typical beauty and fashion tastemakers.

Factors to consider: Marketplaces vs. SaaS

When building a company in this space, it’s important to consider the needs of the creators you’re targeting, as well as their desired audience. There are tradeoffs between marketplaces and SaaS platforms. What’s the difference?

Marketplaces are entirely plug and play, meaning providers can sign up and start earning revenue with minimal set-up. The strength of a marketplace’s two-sided network effect is directly correlated to the value it provides as an intermediary between supply and demand. One example of this model is Medium, which charges readers a subscription fee to access stories across the entire platform. The amount of money a writer makes is proportionate to the amount of time readers spend engaging with their stories.

By contrast, SaaS platforms require creators to work independently to acquire customers. Such platforms might help with distribution—providing tools for marketing, managing customer relationships, and attribution—but users are largely responsible for growing their own businesses. On Substack, for example, features include a writer homepage, mailing list, payments, analytics, and a variety of different subscription offerings. Substack collects a portion of the creator’s subscription revenue.

In the marketplace model, writers count on Medium to drive reader traffic and subscriptions. On the SaaS platform (Substack), writers drive their own direct traffic and subscriptions; they can export their subscriber list at any time.

Marketplaces bring value for creators looking to be discovered and attract customers over time. SaaS tools often make sense for more established creators who already have a customer base. In response to this dynamic, many startups are building SaaS platforms that aim to poach large creators from existing marketplaces.

Looking Ahead

New integrated platforms empower entrepreneurs to monetize individuality and creativity. In the coming years, the passion economy will to continue to grow. We envision a future in which the value of unique skills and knowledge can be unlocked, augmented, and surfaced to consumers.

If you’re building a company in this space, we’d love to chat!

This was originally posted to the a16z blog, which you can subscribe to here.