Ada Lovelace, an early computing pioneer, featured prominently in Walter Isaacson’s book The Innovators

Innovation is messy, and too easy to oversimplify

After finishing Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, I eagerly devoured his followup book, The Innovators. This book zooms out to focus not on an individual, but on the teams of collaborators and competitors who’ve driven technology forward, and the messiness of innovation. The stars of the story turn out to be the often unappreciated women who contributed to computing at key moments, and the book fittingly begins and ends with Ada Lovelace, an 19th century mathematician who defined the first algorithm and loops. I recommend the book, and here are the NYT and NPR write-ups which you can check out as well.

Isaacson’s book resonated with me because once you know how messy the success stories are, it’s obvious why the media always chooses to simplify things down to just a few characters with simple motivations. As a result, we know what kind of shoes that Steve Jobs wears, but forget the names of the people around him who worked for years to make the products we love.

The stories from the book have been floating around in my brain for a few months now, and coincided with two other pieces that went viral on Twitter/Facebook. First, there’s been some great photos of Margaret Hamilton who led the software development for Apollo 11 mission. Second, there was a discussion on Charlie Rose on the women who worked on the original Macintosh. I did some research and put together a few photos of these key pioneers from computing history. Seeing their faces and names help make them more real, and I wanted to share the photos along with some blurbs for context.

If you have more photos to send me, just tweet them at @andrewchen and I’ll continue to update this article.

Women of ENIAC

One of the most interesting backstories in Isaacson’s book is the fact that women mostly dominated software in the early years of computing. Programming seemed close to typing or clerical work, and so it was mostly driven by women:

Bartik was one of six female mathematicians who created programs for one of the world’s first fully electronic general-purpose computers. Isaacson says the men didn’t think it was an important job.

“Men were interested in building, the hardware,” says Isaacson, “doing the circuits, figuring out the machinery. And women were very good mathematicians back then.”

In the earliest days of computing, the US Army built the ENIAC, the first electronic general purpose computer in 1946. And women programmed it – but not the way we do now – it was driven by connecting electrical wires and using punch cards for data.

Left: Patsy Simmers, holding ENIAC board Next: Mrs. Gail Taylor, holding EDVAC board Next: Mrs. Milly Beck, holding ORDVAC board Right: Mrs. Norma Stec, holding BRLESC I board.

Left: Betty Jennings. Right: Frances Bilas

Jean Jennings (left), Marlyn Wescoff (center), and Ruth Lichterman program ENIAC at the University of Pennsylvania, circa 1946.

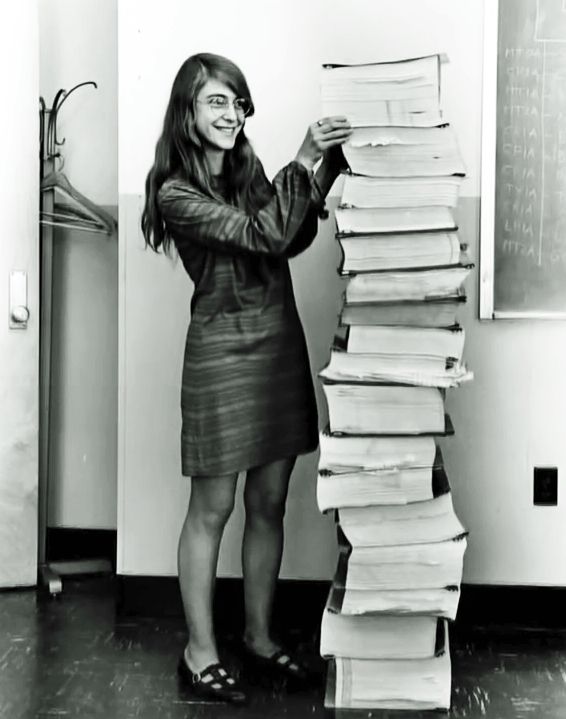

Margaret Hamilton and Apollo 11

Twitter has been circulating this amazing photo of Margaret Hamilton and printouts of the Apollo Guidance Computer source code. This is the code that was used in the Apollo 11 mission, you know, the one that took humankind to the moon. This is how Margaret describes it:

In this picture, I am standing next to listings of the actual Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) source code. To clarify, there are no other kinds of printouts, like debugging printouts, or logs, or what have you, in the picture.

There are some nice articles about this photo on both Vox and Medium, which are worth reading.

Here it is, along with a few other photos of her during this time:

A side note to this that I found pretty nerdtastic is that the the guidance computer used something called “core rope memory” which was weaved together by an army of “little old ladies” in order to resist the harsh environment of space.

To resist the harsh rigors of space, NASA used something called core rope memory in the Apollo and Gemini missions of the 1960s and 70s. The memory consisted of ferrite cores connected together by wire. The cores were used as transformers, and acted as either a binary one or zero. The software was created by weaving together sequences of one and zero cores by hand. According to the documentary Moon Machines, engineers at the time nicknamed it LOL memory, an acronym for “little old lady,” after the women on the factory floor that wove the memory together.

Here’s what it looked like:

Susan Kare, Joanna Hoffman and the Mac

Megan Smith, the new chief technology officer of the United States, was on Charlie Rose recently and referenced the fact that the women who worked on the Macintosh were unfairly written out of the Steve Jobs movie – you can see the video excerpt of her speaking about it here. I tracked down the photo she was referring to, and wanted to share it below.

Macintosh team members: Row 1 (top): Rony Sebok, Susan Kare; Row 2: Andy Hertzfeld, Bill Atkinson, Owen Densmore; Row 3: Jerome Coonen, Bruce Horn, Steve Capps, Larry Kenyon; Row 4: Donn Denman, Tracy Kenyon, Patti Kenyon

On the top of the pyramid photo is Susan Kare, who was a designer on the original Mac and did all the typefaces and icons. Some of the most famous visuals, such as the happy mac, watch, etc., are all from her.

One cool thing to add to your office: Some signed/numbered prints of Susan’s most famous work. I have a couple – here’s the link to get your own.

Here’s a May 2014 talk. Susan Kare, Iconographer (EG8) from EG Conference on Vimeo.

Another key member of the original Mac team, Joanna Hoffman, isn’t in the pyramid photo but I was able to find a video of her talking about the Mac on YouTube, and embedded it below. Here’s the link if you can’t see the embed. She wasn’t in the Steve Jobs movie from Ashton Kutcher, but it looks like she will be played by Kate Winslet in the new Aaron Sorkin film coming out.

Here’s the video:

Bonus graph: Women majoring in Computer Science

Hope you enjoyed the photos. If you have more links/photos to include, please send them to me at @andrewchen.

As a final note, one of the most surprising facts from Isaacson’s book is that early computing had a high level of participation from women, but dropped off over time. I was curious when/why this happened, and later found an interesting article from NPR which includes a graph visualizing the % of computer science majors who are women over the last few decades.

The graph below is from the NPR article called When Women Stopped Coding – it’s worth reading. It speculates that women stopped majoring in Computer Science around the time that computers hit the home, in the early 80s. That’s when male college students often showed up with years of experience working with computers, and intro classes came with much higher expectations on experience with computers.