I’ve been listening to the excellent Season 2 of the podcast Startup, which gives an inside look at YCombinator startup The Dating Ring (NYT coverage here). The episodes are all great. They talk about many important topics, but I had some specific comments on fundraising for dating products.

Here’s a simple fact: It’s super hard to get a dating product funded by mainstream Silicon Valley investors, even though it’s a favorite startup category from 20-something entrepreneurs. There’s a large swath of angels/funds who categorically refuse to invest in the dating category in the same way that many refuse to invest in games, hardware, gambling, etc. Perhaps they’d make an exception for a breakout like CoffeeMeetsBagel (I’m an advisor) or Tinder, but in the main, it’s an uphill battle for dating apps to attract interest. Here’s some data on the few dating cos that have raised.

Obviously, anyone starting a new company in dating should try to understand investor biases in this sector. This essay also compliments a previous one on operating, from HowAboutWe co-founder Aaron Schildkrout, now at Uber, who also wrote about his experiences.

Here are the reasons usually given for why investors don’t do dating:

- Built-in churn

- Dating has a shelf-life

- Paid acquisition channels are expensive

- City-by-city expansion sucks

- Hard to exit

- Demographic mismatch with investors

Let’s break it down.

Built-in churn

Churn sucks, and the better your dating product works, the more your customers will churn*. Every churned customer is a new customer you’ll have to acquire just to get back to even. When you look at a successful subscription service like Netflix or Hulu, you might find a churn rate of 2-5% per month, and you can calculate the annual churn through the following:

Annual Churn = 1-(1-churn_rate)^12

2% monthly churn = 1-(1-0.02)^12 = 21% annual churn

10% monthly churn = 1-(1-0.1)^12 = 70% annual churn

If you have an 70% annual churn rate, you have to have a strategy to replace almost your entire customer base each year, plus a bunch of percentage points to drive topline growth. You can imagine why successful public SaaS companies try to keep their monthly churn under 2%.

So what do the churn rates look like for a dating product? I’ve heard numbers as high as 20-30% monthly. Let’s calculate that:

20% monthly churn = 1-(1-0.2)^12 = 93% annual churn

You read that right. And that means at 20% monthly churn, it gets very hard to retain what you have, much less fill the top-of-funnel with enough new customers to grow the business. Scary.

With most subscription products, the more you improve your product, the lower your churn. With dating products, the better you are at delivering dates and matches, the more they churn! As you might imagine, that creates the wrong incentives. A product focused on casual dating, like Tinder, might escape this dilemma, but dating products generally have built-in churn that’s unavoidable.

Dating is niche and has a shelf-life

All this churn is especially complicated by the fact that the dating market at any given time is pretty niche. Similar to buying a car, refinancing your student loans, or moving into a new house, the reality is that being “in the market” as a single person looking to meet others has a limited time window. Another way to say this is the dating has “intent” the same way that shopping might, especially when you are talking about a paid subscription service. This limits the market size as well as restricting the types of marketing channels you can use to read those consumers.

A similar challenge is that these products aren’t “social” in the same way that Skype or Facebook might be. Although the stigma is quickly passing, it’s not like consumers want to sign up for a dating site and then invite their friends+family to join them on the site. In that way, it’s more similar to a financial or health product, where some privacy is required.

Again, one of the ways that the new generation of mobile dating products solve this is that they are free plus focus more on casual dating. Both factors open up the market to a wider audience, reduce churn, and create opportunities for viral growth.

Paid acquisition channels are expensive

Dating products have historically depended on paid acquisition channels to build their customer base, and other subscription products have generally done the same. In order to make the ROI work, you have to calculate your customer acquisition cost (CAC) versus your lifetime value (LTV) and make sure you are making enough money to support both the marketing as well as operations. In SaaS, you’d try to get a 3X ratio for CAC:LTV but that’s building in some profit for the company – a dating startup might be able to run it closer to the metal to get their initial growth.

Here’s a couple scenarios for products that buy their customers:

- Make a ton of money all at once (example: car/insurance/loan/mortgage leadgen)

- Make a little bit of money over a long period of time (storage, streaming music, etc.)

- Make a little money at first, then grow the revenue over a long period of time (SaaS)

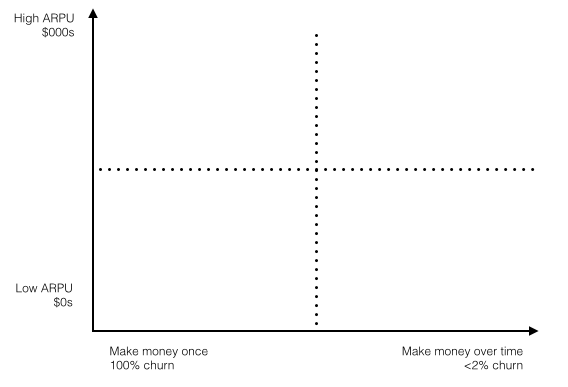

Here’s a visualization of this:

When you start to fill in this chart, you can see a couple things:

First, you’ll observe that of course the “ideal” case might look like a super low churn business that also generates a ton of revenue from each customer. However, the market size might be much smaller than the others. Christoph Janz, a venture capitalist and initial investor in Zendesk wrote a great essay on this topic, called Five ways to build a $100M business that talks about market size as an issue for this.

But back to dating- where does it go? The trouble is, it has some of the same economics for consumer subscription products priced at <$50/month, but at the same time, super high churn that looks like a one-time product. It’s hard to build a high LTV off of that, and so paid channels turn tricky.

Again, this is an area where the new mobile dating apps excel. They have the ability to tap into organic viral/word-of-mouth installs, are super sticky due to their messaging features, and free installs mean infinity return on ad spend (ROAS). At the same time, their focus on casual dating lowers churn and they can monetize via microtransactions. It’s a different model that’s more attractive.

City-by-city expansion sucks

Dating products inherently rely on a local marketplace, and bootstrapping a series of marketplaces is very hard, and expensive. People are willing to travel to meet each other, but only so much. And there needs to be the right mix of male/female participants (or whatever permutation makes sense). To make this work, each city needs to get spun up the same way that on-demand services are spun up, which is one of the reasons why local expansion has remained expensive and unscalable.

This is why we often see dating products continually hold a series of unscalable events/parties/etc in a city to get things going. Until there’s word-of-mouth, and enough people to generate a quality experience, the marketplace will suck. But it’s slow going.

Demographic mismatch with older, married investors

Dating solves a problem that’s most universal and acute for unmarried 18-35yos. Most investors who can write checks (as opposed to associates) are older, married, with kids. Oftentimes they haven’t had to date anyone in decades, unless you’re talking about Ashley Madison. Given this demographic mismatch, it’s a lot harder to get investors to put in the time to really understand the nuances of how one dating product is superior to another. This isn’t just a problem for dating, but also for women’s fashion or startups targeting international markets. It’s tricky, and investors would often rather sit back and wait for traction rather than investing on the merits of a product, something they’re willing to do in other categories. (Thanks to my friend Jason Crawford for adding this point)

Hard to exit

In the end, we’ve seen that dating products often end up being owned by IAC. They own Match, OKCupid, Tinder, HowAboutWe, and others. They have deep experience in local and dating, and the deep pockets to squeeze profit from the category. In contrast, we’ve seen recent dating cos like Zoosk withdraw their IPO plans. I don’t have any inside info, but I’m sure it’s because the churn was high, the channels were degraded, and it was hard to replace lost customers.

In the end, the lack of exits might be more the result, not the cause, of investor disinterest in dating. After all, given the challenges above, it’s very hard to maintain a steady customer base much less grow it consistently year-after-year.

A final note on this: Investor pattern-matching is lazy and often sucks. Google wasn’t the 1st search engine and it wasn’t clear the category was a good investment. Lots of failures. Same with Facebook or Whatsapp. But the investors who won were able to look at the specific characteristics of some of these new companies, rather than looking at the category, and bet that they’d figure it out. Very possible within dating as well, and I wish everyone who’s working in the category that they will be the ones to figure it out.

UPDATE: Fixed some math, thanks Hacker News commenters.