Author Archive

The Adjacent User Theory

Guest Post by Bangaly Kaba (EIR @ Reforge, Former VP Growth @ Instacart, Instagram)

The following was written by Bangaly with contributions by other Reforge EIR’s Elena Verna (Miro, MongoDB, SurveyMonkey) and Fareed Mosavat (Slack, Instacart, Zynga). Reforge is a community for those leading and growing tech companies. To learn more from Bangaly, Elena, and Fareed check out the upcoming Career Accelerator Programs like Product Strategy, Marketing Strategy, and Retention + Engagement Deep Dive.

When I joined Instagram in 2016, the product had over 400 million users, but the growth rate had slowed. We were growing linearly, not exponentially. For many products that would be viewed as an amazing success, but for a viral social product like Instagram, linear growth doesn’t cut it. My job was to help the team accelerate and get back to exponential growth. Over the next 3 years, the growth team and I discovered why Instagram had slowed, developed a methodology to diagnose our issues, and solved a series of problems that reignited growth and helped us get to over a billion users by the time I left.

Our success was anchored on what I now call The Adjacent User Theory. The Adjacent Users are aware of a product and possibly tried using the it, but are not able to successfully become an engaged user. This is typically because the current product positioning or experience has too many barriers to adoption for them.

While Instagram had product-market fit for 400+ million people, we discovered new groups of users who didn’t quite understand Instagram and how it fit into their lives. Our insight was that it is critical for growth teams to be continually defining who the adjacent user is, to understand why they are struggling, to build empathy for the adjacent user, and ultimately to solve their problems. And Adjacent User Theory doesn’t just apply to hyper-growth machines like Instagram, I’ve seen the dynamic play out again and again at plenty of other product-driven companies.

The Importance Of The Adjacent User

Solving for the Adjacent user is critical for a few reasons.

Solving For The Adjacent User Captures The Potential Of Current Product Market Fit

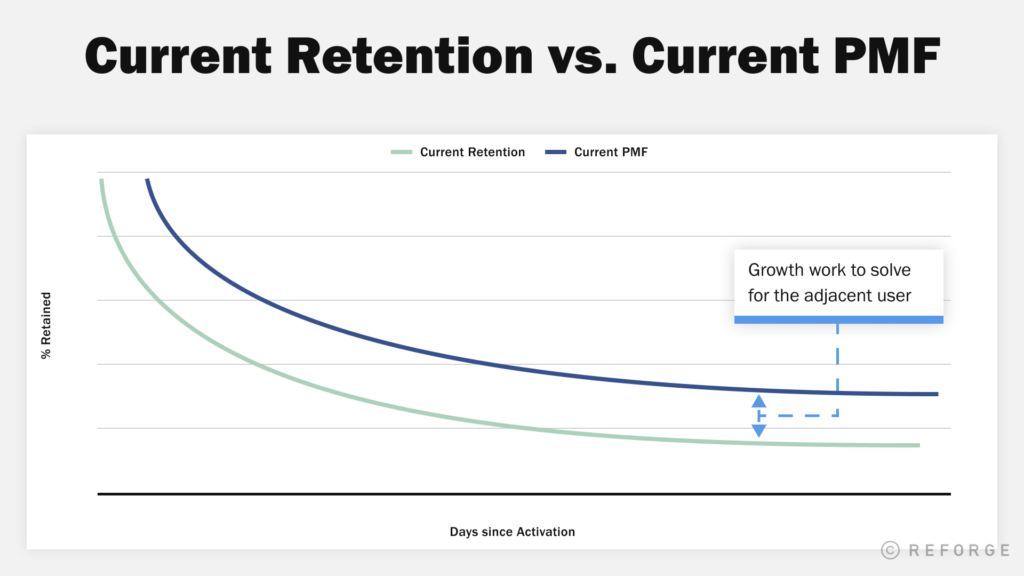

When you have Product-Market Fit, you have healthy retention curves (they flatten out). But this isn’t the end goal. Your current retention doesn’t represent the true potential of your current product-market fit. There is a hypothetical retention curve that sits above that represents this true potential.

What creates this gap? There are a set of users who show intent for your product but are not quite able to get over the hump. Those are your Adjacent Users. Solving for the Adjacent User through growth and scaling work helps your product realize its true product-market fit potential.

The Impact Of Solving For The Adjacent User Compounds Over time

Every year there are massive efforts to getting voters to register and get to the polls. Those voters not only impact the outcome of one election, but can change the engagement of future elections and generations of politics.

In a similar way, when you enable adjacent users to successfully experience the core value proposition, it not only changes the engagement of near term cohorts but flows through to creating impact for all future cohorts of users. This doesn’t just impact retention, but flows through your growth loops to impact acquisition and monetization as well.

The Adjacent User Is A Different Way To Focus Product Efforts

Most product teams know their existing users pretty well. But your future audience is always evolving. The challenges that these potential users face in adopting the product increase over time. Without a team dedicated to understanding, advocating, and building for your next set of users, you end up never expanding your audience. This stalls growth, and the product never reaches the level you aspire it to.

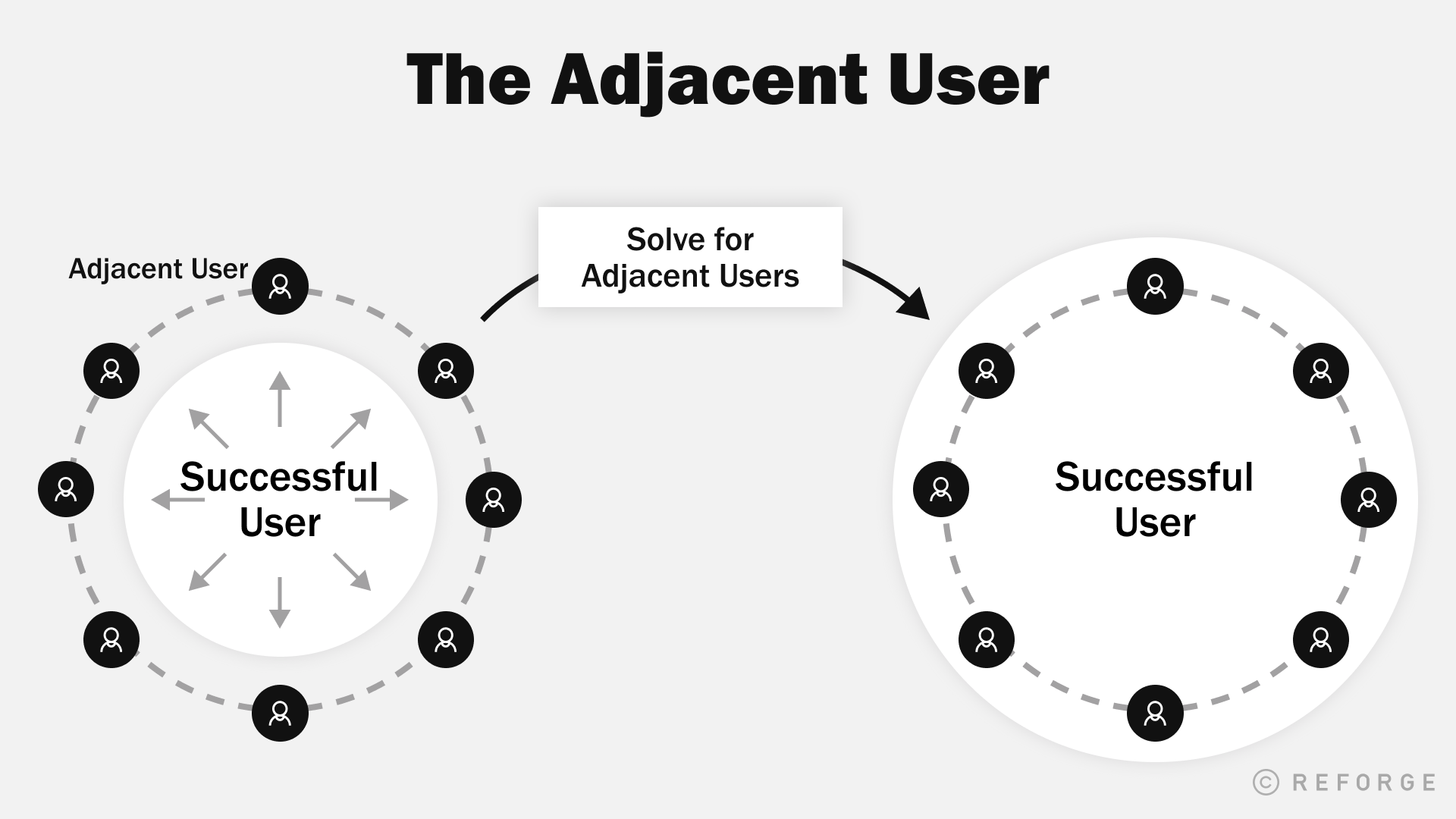

Going Deeper On The Adjacent User

You can think about your product as a series of circles. Each of these circles is defined by the primary user states that someone could be in. For example Power, Core, Casual, Signed Up, Visitor. Each one of these circles have users that are “in orbit” around it. These users have an equal or greater chance they drift off into space rather than crossing the threshold to the next state. There is something preventing them from getting over the hump and transitioning into the next state. These are your adjacent users and the goal is to identify who they are and understand their reasons struggling to adopt. As you solve for them, you push the edge of the circle out to capture more of that audience and grow.

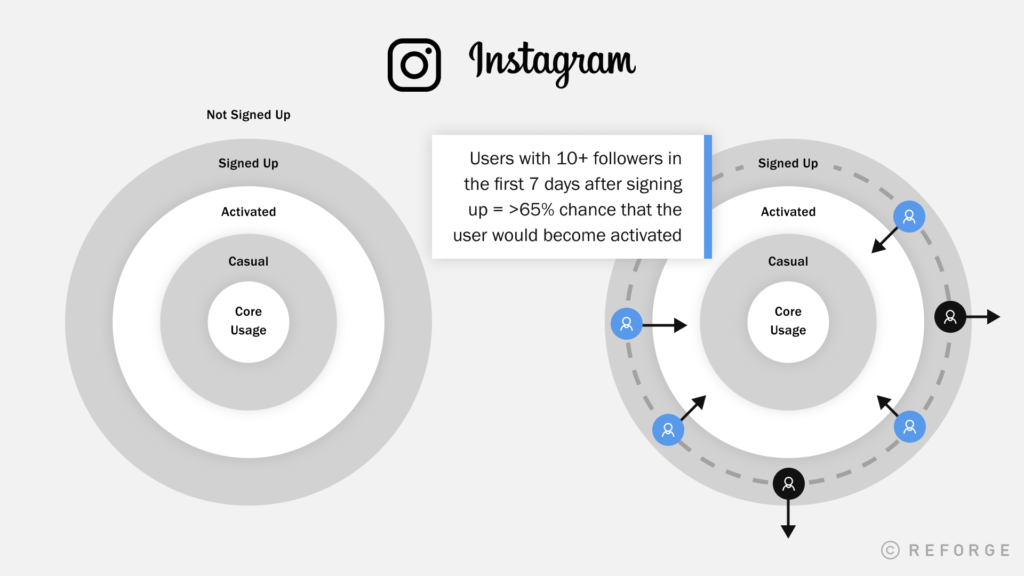

Instagram Example Of The Adjacent User

Lets go through a couple of examples, starting with Instagram. The primary thresholds that a user has to cross to becoming a core user:

- Not Signed Up → Signed Up

- Signed Up → Activated

- Casual → Core Usage

At each one of these thresholds, there are users that are circling around them, that have an equal or greater chance of not crossing the threshold.

Bangaly: “At Instagram, if a user had more than 10 followers in the first 7 days after signing up there was over a 65% chance that the user would become activated. There was always a group of users on that margin that would struggle to build their audience. But the reasons they struggled varied across different sets of user and changed over time.”

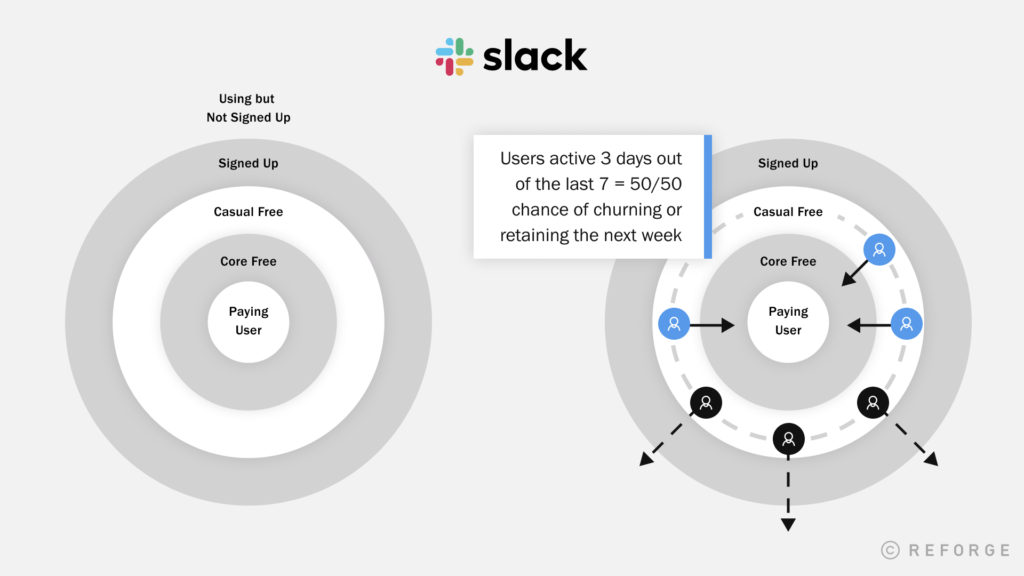

Slack Example Of The Adjacent User

Lets go through an example for Slack. The primary thresholds that user has to cross through are:

- Not Signed Up → Signed Up (Acquisition Teams)

- Signed Up → Casual (Activation Teams)

- Casual → Core Free (Engagement Teams)

- Core Free → Monetized (Monetization Teams)

At each one of these thresholds, there are users that are circling around them, that once again have an equal or greater chance of just drifting off into space.

Fareed: “At Slack, we found that if a user was active 3 days out of the last 7 (3d7), they were right on the edge and had a roughly 50/50 chance of churning or retaining the next week.”

Why Teams Don’t Focus On The Adjacent User

There are a few things that tend to lead teams away from focusing on the adjacent user:

- Focusing On The Power User

- Personas Are The Wrong Tool

- Trying To Hit A Home Run On Every Swing

The Gravity Of The Power User

Product teams by nature are power users of their own product. The parts of the product that the product team uses, tend to automatically get improved as the pain is right in front of them. But this leads to building for yourself (or your friends). While that can feed the ego, if you are only building for yourself or power users, you won’t grow. You need to constantly be building for that next user that doesn’t have the same level of knowledge, intent, or needs that you, your team, and your power users already have.

Working on the adjacent user requires you to cross a cognitive threshold. You have to specifically seek out the definition to “see” them and understand their experience, which is likely to be dramatically different from what you see as an employee. Once you see them, you can build empathy for them and their struggles, which in turn informs what you build.

Andrew: “At Uber, a lot of employees were power users of the Uber product. This led to a lot of voices thinking they knew what we needed to grow just because they used the product a lot. But these were rarely the things that pushed growth of Uber into new audiences.”

Personas Tend To Be The Wrong Tool

When trying to answer the question of who they are trying to solve for, product teams often use their stated personas as the answer. But personas, as they are typically defined, have one or more of the following issues:

- Current User vs Next User – Product personas tend to describe who your current users are. The adjacent user is a forecast of who your next user is so that you can enable the things to make them successful.

- Too Static – A company will often come up with their personas and anchor on them for years, never evolving and updating them. The definition of your adjacent user should be evolving and changing more frequently as you solve for one and move to another.

- Too Broad – Personas tend to be too broad to be actionable. Living beneath a lot of persona definitions are many sub-segments. The adjacent user is about having a view on those sub-segments living at the edge of who the product is working for today.

- Not Based on Usage – Companies often build personas based on demographic factors and emotional needs. While these are valuable for many applications, they won’t help you solve adoption issues for adjacent users unless you also include their usage barriers in your definitions.

Trying To Hit A Home Run Every Time

Product teams overvalue hitting home runs vs hitting 100 singles back to back. This leads them to take bigger swings by going after bigger markets of new users. They get bogged down by trying to establish product-market fit for a new set of users and never fulfill the potential of their current product-market fit.

Remember, adjacent users are the users who are struggling to adopt your product today. Non-adjacent users could literally be everyone else in the entire world. Sure, non-adjacent users might be a larger market, but the barriers to their adoption are also dramatically higher. Companies that try to go too big too soon and often, skip the next obvious steps and fail to solve their current adoption problems.

Solving for the adjacent user is often seen as “optimization”, which in some organizations is viewed poorly because they represent short-term thinking. Solving for your adjacent user is not short term thinking; it is this disciplined sequential execution that will enable your longer-term roadmap and faster growth. It is short turns on a longer term path, not short term.

How To Know The Adjacent User Is Here

Until you recognize that they are adjacent users and commit to helping them, they will remain adjacent. They aren’t going to get there on their own. You have to be passionate about them and learn to view the product from their eyes. If you don’t focus on them, growth slows and your cohorts decay.

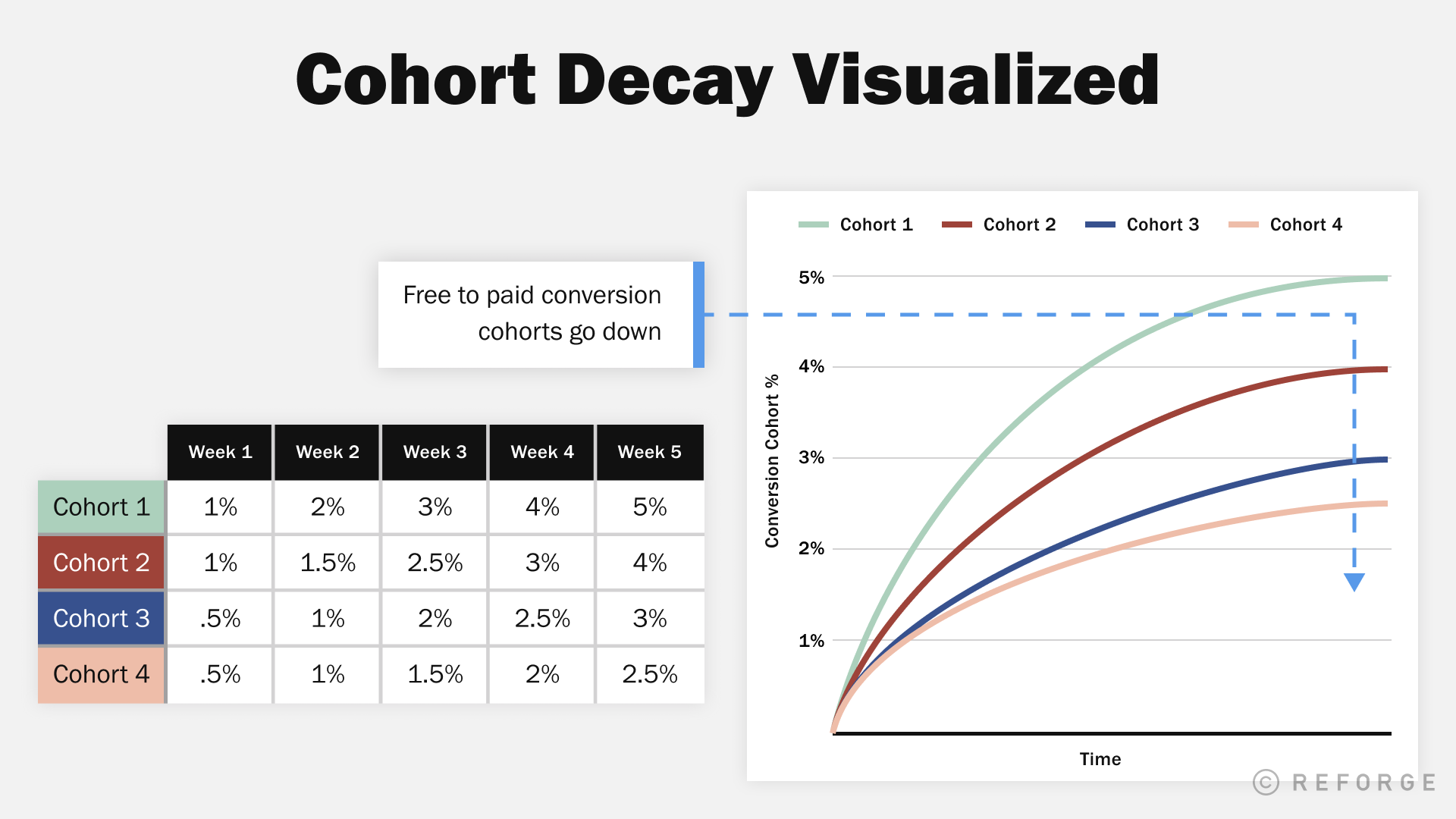

Cohort Decay Is Your Signal

At a high enough volume of users, you will start to see the effect of the adjacent user show up in your cohorts. Sitting at the edge of each user state is a quantitative metric that indicates conversion from one state to the next. For example, free to paid conversion or signed up to activated.

When you look at these variables on a cohorted basis, you will almost always see a decline from cohort to cohort over time. This is because there is some segment of adjacent users that are entering that state and struggling to convert to the next.

Elena: “When you start investing into new channels (especially paid) it is typically a signal to the product org that adjacent users are coming. New channels bring in users that will be different on some vector. Lower intent, less solution aware, less brand aware, pain point not completely formulated, or something else.”

Slack Example of Cohort Decay

Fareed: “A common thing I see across freemium SaaS companies I advise, is free to paid conversion decline from cohort to cohort. This is your signal that there are a set of adjacent users on the edge of this state that you need to start solving for.”

What Fareed’s story is pointing out is that at the edge of Core Free → Paying User, the metric that monitors that edge is free to paid conversion. Over time, if you look at that metric on a cohorted basis, you will start to see the metric go down from cohort to cohort. This can happen at the edge of any user state (signup to activated, activated to core, etc).

Discovering and Defining Your Adjacent Users

The first step to seeing the product through the eyes of the Adjacent User is to build a hypothesis of who they are and why they are struggling. How do we do that?

The Goal Is To Get Visibility, But Not Perfect Visibility

The goal of defining your adjacent users is to get visibility, but not perfect visibility. You need to define the landscape in front of you to understand all your options and figure out which type of adjacent user to focus on. Knowing just one adjacent user segment isn’t enough because you often have several to choose from.

But there are equal problems trying to get perfect visibility. You will never have perfect visibility and perfect definitions. If you seek out understanding perfect visibility you will never get started.

The process is to lay out multiple hypotheses of who the adjacent users are, choose which one to focus on strategically, force your team to look at the product through their lens, experiment and talk to customers to validate and learn, then update the landscape to make your next choice. I like to think about it as a snowball. You know very little at first, but as the snowball turns you collect more information about the adjacent user, which helps you collect more snow (users).

Knowing Who Is Successful Today and Why

To understand your adjacent users, it is helpful to understand the attributes of who is successful today and why they are successful. The reason this is helpful is that your adjacent user is different on one or more of these attributes (but not all). These attributes create vectors of expansion. Lets go through an example.

At Instacart, we knew that over 75% of our core, healthy users were:

- Women

- Urban

- Located In Certain Cities

- Head of Household

- Had one or more kids

- Were more affluent and less price sensitive

- Willing to spend an hour filling up their Instacart Order

Some of these things we knew from data. Some of these thing we knew from customer conversations. Some of them we knew by inference. Each one of these attributes creates vectors of expansion

- Women → Men

- Urban → Suburban

- Cities → Other Cities

- Head of Household → Members of households

- 1 Kid → Smaller Families, Couples, Singles

- More Affluent + Less Price Sensitive → More Price Sensitive

- Willingness to put effort in the cart → Less willingness to spend that time

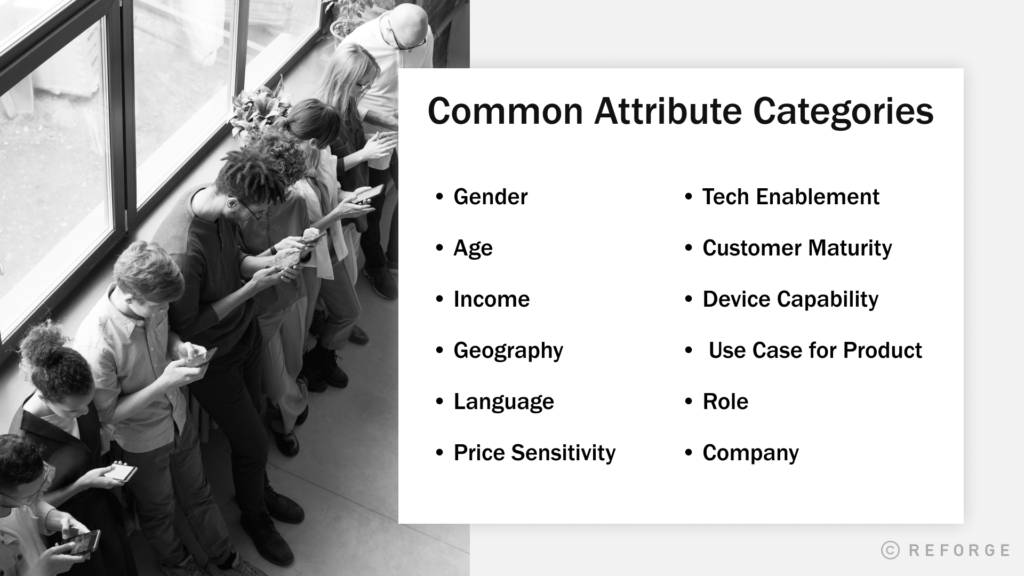

The more granular you can get, typically the better. But there are a set of common categories for attributes. Which categories are relevant and most impactful depend on the product:

- Gender

- Age

- Income

- Geo

- Language

- Price Sensitivity

- Tech Enablement

- Customer Maturity

- Device Capability

- Use Case for The Product

- Role

- Company

Who Is The Adjacent User?

Once you have hypotheses for who is successful and why they are successful, you can hypothesize possible adjacent users segments. This will involve changing one or more of the vectors that you identified.

I typically recommend starting with a bottoms-up analysis of your data. You do not need to spend weeks talking to users to get a sense for who your adjacent user is. Look at what is happening on the edges of these states in the data. The data will help you identify places in the product that people are dropping off. This is the starting point to help you develop hypotheses about why different segments of users are dropping off.

At Instacart, when we initially looked at the data, we found that it took a really long time for current successful users to create their first order. As we looked through that flow, it became an understandable problem. For someone that had never placed an order, there were tens of thousands of products, and this person wanted to find a specific product quickly. Our hypothesis was that current users were very high intent users who were willing to spend an hour filling up their cart versus driving to the store. It led us to start focusing on the discoverability of products within first use to capture users with less intent.

At Instagram, when we first looked at the data, we started to see an enormous amount of organic web traffic showing up, but they weren’t converting to sign-ups and healthy users. We didn’t have any idea why. But through a lot of data exploration, we started to figure out where those users were coming from, why they were coming via web traffic, and other reasons that helped us define the adjacent user.

When you have an early hypothesis of who the adjacent user is from the data, use that to inform who you recruit for user research. Those customer conversations help you do two things: One, validate and fill in your hypotheses on who the adjacent user is; and two, start to build empathy for the adjacent user and understand why they are struggling.

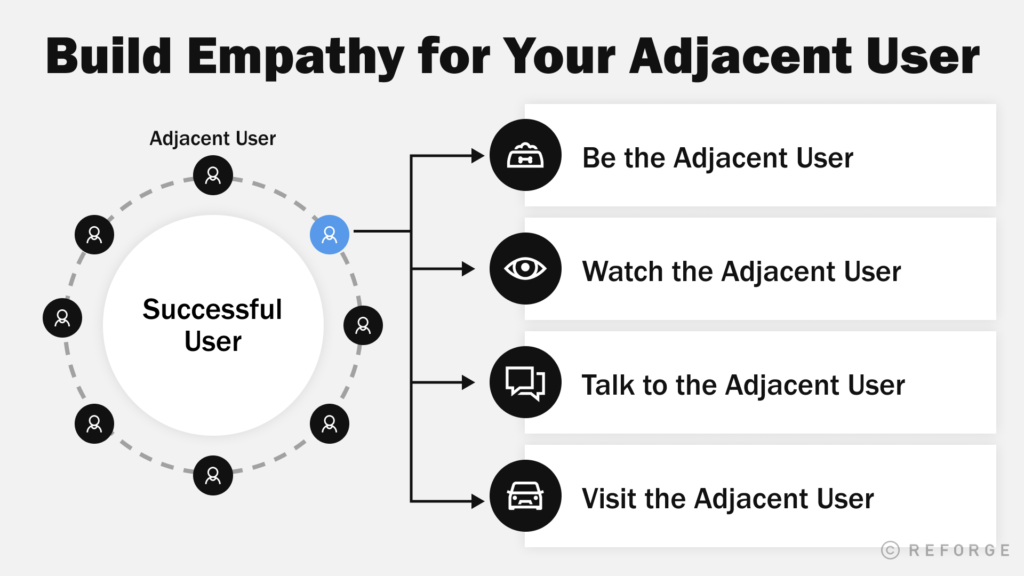

Why Are They The Adjacent User?

It is not enough to know who the adjacent user is, but you need to know why they are struggling. To do that, you have to build empathy with the adjacent user. This is the most important part.

Building empathy for the adjacent user is hard because by definition your team is not living the experience of the adjacent user. Your team are power users of the product. They know the product in and out. To build empathy with the adjacent user and create hypotheses of why they are struggling, I recommend four techniques:

- Be The Adjacent User

- Watch The Adjacent User

- Talk To The Adjacent User

- Visit The Adjacent User

Lets talk about each of these individually.

Be The Adjacent User

You need to force the team to be the adjacent user by experiencing the product in the conditions and settings that the adjacent user is experiencing. This is commonly referred to as dog-fooding. This starts by making sure the team is constantly experiencing new user flows, empty states, and product states that require a certain amount of usage before they become valuable.

This eventually progresses to building tools to be able to simulate the experience of your adjacent users. For example, at Instagram as our adjacent users increasingly became more international, we needed to find a way to experience the product across many permutations of devices, network speeds, languages, and much more. Facebook built something called Air Traffic Control, which simulated elements of these permutations like network speed so the team could experience the product through the eyes of the adjacent user.

At Instacart, we had to find ways to experience the product through the eyes of someone in an expansion market like Overland, Kansas. There the store options, delivery windows, and other factors were completely different than what a PM or engineer on the team in San Francisco would be experiencing.

Living every day as the adjacent user uncovers hidden connections and dependencies in the product that impact the experience for the adjacent user that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

Watch The Adjacent User

The second technique is to watch the adjacent user using your product through usability tests. Ideally this is done with trained researchers when possible. Watch the adjacent user try to sign up, activate, see what they struggle on, have them talk about why they are having challenges and what their expectations of the experience are.

Do not help them until they get stuck so you can observer what kind of workarounds and hacks people create to get the outcomes they want. This is how you start uncovering behavior that explains aberrant data, or behavior for which data doesn’t exist.

Talk To The Adjacent User

The third technique is to talk to the adjacent user about why they are trying to use your product, what jobs they are trying to solve, and which alternatives they are considering or have already tried. Surveys are fastest to deploy to get signal on where you should spend more time and focus. But surveys alone are not sufficient. You need to talk to users in person to go deeper.

At the beginning of the post I talked about the example at Instagram where we started to see a large increase in access churn (users logging out, then failing to log back in successfully). Two directions emerged. We could either make it harder for people to log out, or easier to log back in. But to determine which path was best, we needed to understand why people were logging out in increasing volumes.

We decided to talk to a lot of users who were intentionally logging out. What we found were two things:

- People had a real use case for logging out. They logged out either because they had a prepaid phone plan and were worried about background data usage, or they were sharing the phone with a family member.

- These users also commonly used fake email addresses. Email addresses are more of a western paradigm, and new people to the internet internationally don’t use email, they just text.

Once we understood these two things, it was clear the right strategic direction was to work on making it easier to log back in vs harder to log out and we were able to come up with some creative solutions for the use cases.

Visit The Adjacent User

The last technique is to visit the adjacent user in their environment. Seeing how your adjacent user uses a product in their environment expands your understanding of their workflow, constraints, and needs. Are B2B customers constantly sharing screens with colleagues for a product that you previously thought of as a personal tool? Are users having performance or usability issues in the real world that you otherwise wouldn’t have considered? Users tend to employ their authentic workarounds and habits in their own environment, which you won’t see in a lab or other manufactured setting.

Sequencing Your Adjacent Users

One of the biggest failure points is sequencing your adjacent users incorrectly. You want to pick the right adjacent users to go after so that you are building towards longer term value over time.

If you are familiar with Geoffrey Moore Crossing The Chasm, he referred to something similar called the bowling alley strategy. Find one niche audience that if you solve for them, helps you get to the next audience.

The center of Moore’s framework was Customer Maturity: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards. Moore theorized that by solving for the problems of next set of likely adopters you enable the following segments. Adjacent User theory is similar. By enabling your immediate next set of adjacent users, you create the conditions that enable future segments. You can push the boundaries of the core user outcomes down to a lot of vectors, customer maturity being just one.

How To Think About Sequencing

There are a few keys to sequencing segments of Adjacent Users.

1. Adjacent User Should Only Be Different On One or Two Attributes

Let’s say you have 5 different vectors you can expand on. If your adjacent user definition is different on all 5 of those vectors, or even the majority, choosing that segment is a bad choice. That is like trying to hit a home run on every swing. It is probably going to take too many changes that are too large to enable that segment.

You need the conviction that you can build something to validate or invalidate the adjacent user definition pretty quickly. The adjacent user is not about capturing one large definition at once, it is about layering on micro definition after micro definition.

Elena: “A segment that is different on multiple attributes typically requires enabling a new value prop to bring them into the product. That’s a very big swing. But it’s not an “if” you should be going after them, it’s a question of “when.” If you can first add smaller features for adjacent users that only differ on one attribute you can maintain momentum and growth velocity while working up to a new value prop for those multi-attribute users.”

2. Not All Adjacent Users Are Opportunities

As you explore your adjacent users, you are going to find a lot of possible segments. But just because they exist, does not mean you should choose to serve them. The key here is that the segment still needs to align with the strategic direction of where the product is going.

Sometimes you will have a lot of insight that an adjacent user exists, but you are unsure if serving them is meaningful and aligns with the strategic direction. This happened while working on Instagram. As we solved access churn (people churning because they had trouble logging back in) we noticed feed posts were going up. At first, we didn’t know why, but we eventually discovered people had 2nd and 3rd accounts that they were logging back into. One account was public-facing, and one was more private for friends. So the question came up, should we be more intentional about making it easier to create and navigate across multiple accounts? Is that meaningful? Does it align with the strategic direction of the product? We didn’t have a clear answer and therefore punted on that adjacent user until we had further validation that the 2nd account was an additive opportunity within our strategic direction.

3. Solve In-House Problems First

When choosing your adjacent users, it is typically better to solve “in-house” problems first. These are users that are already showing up in your funnel and product vs brand new users who aren’t there yet. Those that are already showing up are displaying intent, but having trouble finishing. Solving for them typically creates more short term impact.

Elena: *”For B2B products, the way I like to think about sequencing is:

- First solve for those in the existing user base that can drive additional monetization.

- Second, solve for those in the existing user base that drive additional value in indirect ways. For example, a user might not monetize well but drive tons of viral contribution.

- Third, solve for the brand new adjacent user. These are people not showing up in the user base, but still share traits with the existing user base.”*

Part of the prioritization should be the impact that you think the adjacent user segment can drive if solved for. The impact is partially driven by the size of the segment today. But one mistake when thinking about impact is to not think about the impact on a longer time horizon. Often times one segment might be larger but not growing, while another could be smaller but have a much larger growth trajectory. When taking that trajectory into account, the second segment may be the better choice.

Fareed: “When we were looking at international growth opportunities at Slack, we found that both users in France and India had far worse monetization. A lot of teams would have probably chosen to solve for French users since they are a higher income audience.

But users in France weren’t growing and we didn’t have a clear hypothesis of why they weren’t monetizing. On the other hand, India was growing way faster and had a clear hypothesis as to why they weren’t paying. When looking at it on a slightly longer term horizon, solving for users in India was clearly the higher ROI opportunity.”

The Evolving Adjacent User Landscape

The landscape and understanding of your adjacent users are always evolving. When I started at Instagram, the Adjacent User was women 35 – 45 in the US who had a Facebook account but didn’t see the value of Instagram. By the time I left Instagram, the Adjacent User was women in Jakarta, on an older 3G Android phone with a prepaid mobile plan. There were probably 8 different types of Adjacent Users that we solved for in-between those two points.

Your Adjacent User is constantly changing for a few different reasons:

- New InformationAs you experiment and solve for one adjacent user, you are constantly gaining new information. This can happen in a few ways:

- Unexpected Result – You run an experiment and get a result you did not expect.

- New Instrumentation – New data instrumentation creates visibility into what is happening in areas you didn’t have visibility before.

- New Research – Through the course of user research to validate hypotheses, you uncover new hypotheses you hadn’t thought about before.

This new information informs updates to your current adjacent user hypotheses and possibly creates entirely new adjacent user segments.

- New Users Showing UpAs you unlock value for one type of adjacent user, they often start bringing in a new type of adjacent user into your orbit. All healthy products have some acquisition through word of mouth. So when you solve for one adjacent user, their word of mouth brings in their friends who just might be your next type of adjacent user.Unlocking the 35-45yo women in US and Europe on IG brought WOM growth through families. This is an important age group for mothers who would create private IG accounts to share family and kid photos. This influenced their friends to do the same, inspired other relatives to sign up just to see these photos, and their partners ended up joining as well

- New Value PropsAs the product team enables new value props in the product, it can fundamentally change what the experience needs to be at the edges of user states for adjacent users to experience the product.At Instagram, this occurred when we launched Stories. Stories didn’t help activate new users. It actually made it harder. It was hard for new users to have available Stories content because it disappeared after 24hours. Users needed to follow a lot more accounts to have enough content on any given day. The bar was higher and it changed the experience of how we created activation and engagement.

Knowing that the adjacent user is constantly changing, we would reevaluate our understanding of the adjacent user every quarterly planning cycle based on learnings from experimentation and research. In addition, we would tend to have one off insights a couple of times per year from various events like unexplainable experiment results, press, surveys, or something else. This evolving landscapes highlights the importance of a few different things:

- Taking Time To Understand The WhyToo often teams move on from the positive/negative result of an experiment without understanding why the experiment generated that result. You must take the time to understand “the why’ behind your experimental results. The why helps you understand the next adjacent user. If you don’t do this you can miss incredibly important shifts in user mindsets as you move from adjacent segment to segment. If you don’t take the time to understand the why behind your results, you miss the opportunity to build empathy and solve your adjacent user’s real problems.

- Constantly Working On the Fundamentals Of Registration, Activation, Engagement and MonetizationToo often teams treat key flows in their product as projects. But the adjacent user highlights why you need to be constantly working on the fundamentals of registration, activation, engagement, and monetization. It’s a continuously evolving user challenge that you need to be constantly re-evaluating. The work never stops.Fareed: “In the early days of Instacart, the best performing landing page was an all white page, that said “Instacart, Groceries delivered to your door, put your zip code in”. Nothing else performed better. The user at that time was very high intent, tech savvy, urban millennial who knew what Instacart was because they heard about it from a friend through the press. As Instacart grew over time, you had to explain what Instacart was, why does it matter, who it is for, what stores we have. The same experiment on the white page a year later had dramatically different results because the adjacent user had changed.”

- Continually Cross The Cognitive Threshold Of Your Adjacent UserAt the beginning of this post, we talked about how working on the adjacent user requires you cross a cognitive threshold of seeing the product experience through their eyes. As the landscape of the adjacent user evolves, you and the team need cross this threshold over and over. It is easy to get sucked back into the gravity of your existing user base. But your job is to constantly expand the definition of who is successful with your product.

All successful products must eventually shift their focus from core to adjacent users in order to maintain growth rates. Rapid success in your first audience will inherently lead to saturation and declining growth in that segment. While this is certainly an enviable problem to have, solving it is one of the most complex challenges in technology. The most successful companies are the ones that can continuously evolve to serve more adjacent users. The art is selecting the right groups of adjacent users to go after next. If you try to solve all problems for everyone, you’ll drown across too many issues and waste time acquiring users who have no chance of being successful today.

Adjacent User Theory demands an entirely different approach to being ‘user centric’. Static personas are OUT. Dynamic evolving personas that incorporate product adoption behavior are the standard to strive for. Every 3-6 months during hyper growth, you have to reorient your team around the next adjacent user, what they care about, and what problems you are solving for them.

As you are succeed, you’ll see improving cohort retention, engagement, and monetization in your target adjacent users. You’ll maintain your growth rate on larger and larger install bases. And you’ll continuously discover the next adjacent user who could use your product with just a little more help.

—

If you want to learn more from Bangaly and other leaders from top tech companies, check out Reforge’s upcoming Career Accelerator Programs such as Growth Series, Experimentation and Testing, and Monetization Deep Dive. Reforge programs distill invaluable knowledge from top leaders and deliver decades of career experience in an intensive 6-week part-time format.