Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Mobile app startups are failing like it’s 1999

Stop the madness

The long cycle times for developing mobile apps have led to startup failures that look more like 1999 – it’s like we’ve forgotten all the agile and rapid iteration stuff that we learned over the last 10 years. Stop the madness!

Today, seed stage startups can now get funded, release 1 or 2 versions of their app spread over 9 months, and then fail without making a peep. We learned the benefits of how to iterate fast on the web, and we can do better on mobile too.

How things worked in 1999

How’d we get here? Back in 1999, we did a similar thing:

- Raise millions in funding with an idea and impressive founders

- Spend 9 months building up a product

- Launch with much PR fanfare

- Fail to hit product/market fit

- Relaunch with version 2.0, 6 months later

- Repeat until you run out of money

This was Pets.com, Kozmo, and so on. Maybe you’d fire your VP Marketing in the process too, out of frustration.

Between 2002-2009, we learned a lot of great ways to work quickly, deploy code a few times a week, and get very iterative about proving out your product.

How things work today

Then, with the arrival of the big smartphone platforms, we’ve reverted. It looks like 1999 but instead of launching, we submit into the iOS App Store.

It looks like this instead:

- Raise funding with an idea and impressive founders

- Spend 6 months building up a product

- Submit to the app store and launch with much PR fanfare

- Fail to hit product/market fit

- Relaunch with version 2.0, 6 months later

- Add Facebook Open Graph

- Try buying installs with Tapjoy, FreeAppADay, etc.

- Repeat until you run out of money

Not much different, unfortunately.

The platform reflects its master

We’ve gotten here because the App Store reflects Apple’s DNA of great products plus big launches. They are a 1980s hardware company that’s mastered that strategy, and when developers build on their platform, they have no choice but to emulate the approach as well.

Worse yet, it lets people indulge in a little fantasy that they too are Steve Jobs, and once they launch a polished product after months of work, they’ll be a huge success too. The emphasis on highly polished design for mobile products reverts us back to a waterfall development mentality.

Don’t burn 1/2 of your funding to get to a v1

Startups today have a super high bar for initial quality in their version 1. They also want to make a big press release about it, to drive traffic, since there’s really no other approach to succeed in mobile. And so we see startups burn 1/3 to 1/2 of their seed round before they release anything, it becomes really dangerous when the initial launch inevitably fails to catch fire. Then the rest of the funding isn’t enough to do a substantive update.

What can we do?

How can we stop the madness? What can do we do to combine the agility we learned in the past decade with the requirements of the App Store?

If we can answer this question, we’ll be much better off as an industry.

Why companies should have Product Editors, not Product Managers

One of the most compelling organizational things I’ve read about lately is Square’s practice of referring to their product team as Product Editors and the product editorial team, rather than the traditional “Product Management” title. Wanted to share some quick thoughts below about it.

Product managers: One of the toughest and worst defined jobs in tech

The role of “product manager” “program manager” “project manager” is one of the toughest, and worst defined jobs in tech. And it often doesn’t lead to good products. The various PM roles often have no direct reports, but you have the responsibility of getting products out the door. It often becomes a detail-oriented role that are as much about hitting milestones and schedules as much as delivering a great product experience.

Thus PMs sometimes end up in the world of Gantt charts, 100-page spec documents, and spreadsheets rather than thinking about products. Now, all the scheduling and management tasks matter, but it’s too easy for PMs to lead with them rather than leading with products first.

Bad ideas are often good ideas that don’t fit

In the context of literature, books, and newspapers, it’s the job of the editor to pick the good stuff and weave it into a coherent story. You remove the bad stuff, but “bad” can mean it’s a good idea but just doesn’t fit into the story. It’s a compelling and important distinction for consumer internet.

Cohesion and consistency is difficult. When you have an organization with lots of very smart people all with their own good ideas, it’s difficult to decide which path to take. So often, products are compromised as the product “manager” doesn’t feel the responsibility to build up that cohesion as an ends in itself, and instead just tries to do as much as possible with the product given some set timeframe. Focus, people!

Jack Dorsey in his own words

In a recent talk at Stanford, Jack Dorsey describes his idea of editors:

“I’ve often spoken to the editorial nature of what I think my job is, I think I’m just an editor, and I think every CEO is an editor. I think every leader in any company is an editor. Taking all of these ideas and editing them down to one cohesive story, and in my case my job is to edit the team, so we have a great team that can produce the great work and that means bringing people on and in some cases having to let people go. That means editing the support for the company, which means having money in the bank, or making money, and that means editing what the vision and the communication of the company is, so that’s internal and external, what we’re saying internally and what we’re saying to the world – that’s my job. And that’s what every person in this company is also doing. We have all these inputs, we have all these places that we could go – all these things that we could do – but we need to present one cohesive story to the world.”

A video of Jack Dorsey talking about the concept can be seen here:

Lead with product

What’s compelling to me about this is that it really orients the role of product to be about cohesive experiences first and foremost. OK, yes, there’s still schedules first, but it doesn’t drive the thing- great products drive the process.

Similarly, you don’t just jam lots of characters and plot points in a story just because. Even if they are good characters, it can bloat the story. Same with features- sometimes you have many, many good ideas for your product, but if you come to do all of them, you ultimately make it a confusing mess. Instead, you have to “edit” down the feature list until you have a clean, tight experience.

Anyway, I hope to see this trend continue in the tech industry – it sets the right tone for where we should all be focused.

Don’t just design your product, design your community too

Design is in.

Consumer startups no longer need to argue about product quality – it’s a prerequisite to even an initial launch. This is a good thing, but this post isn’t about that.

For social apps, what you design directly is only half the user experience. The people are just as important! So if you build a really great linksharing site that’s extremely polished and full-featured, but the community consists of Nazis, it won’t work for people.

I’m often reminded of this fact when trying XBox Live, which consists of prepubescents killing you repeated on Halo while calling you gay. The Halo content is amazing, of course, but the community around it is… um… different than me.

Dribbble as an example

Similarly, you could build a product that was an exact replica of uber-design site Dribbble, yet still fail if you didn’t have their users. Half the work is the functionality, but the other half is “designing” the right users. If you haven’t seen the rules, a lot of things have to happen before you’re allowed to actually post content there:

- Why are players drafted? http://dribbble.com/site/faq#faq-why-drafted

- “Undrafted prospects” http://dribbble.com/designers/prospects

Basically, they have a long line of “prospects” which have to be nominated by the community in order to be able to post content. They limit membership like this so that all the content on the site will only be the very best.

Eventually, opening up is key

Perhaps naturally you eventually open up and evolve beyond this, but I think at the beginning you still need a lot of authenticity.

I think the reason why this whole concept feels unfamiliar to me is that for most consumer products, the problem is getting more people, not rejecting them :) Yet at the same time, I’ve learned through a lot of first-hand experience that if you don’t curate the initial community and scale your traffic as a function of this group, you can easily fall into the trap of “designed product, but undesigned community.” That’s no good either.

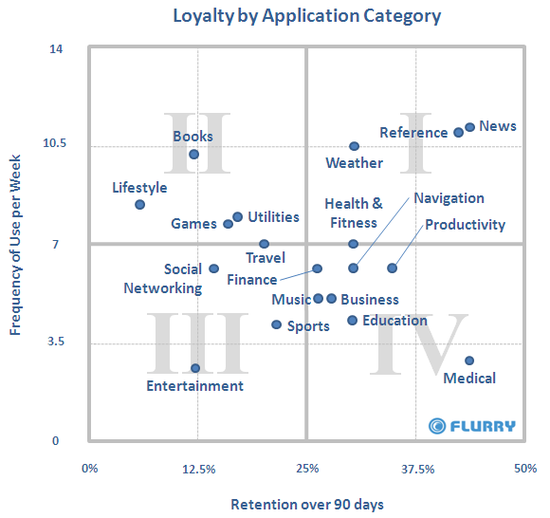

What factors influence DAU/MAU? Nature versus nurture

Surprisingly, it can be hard to figure out if you’re at Product/Market Fit or not, and one of the big reasons is that comparable numbers are difficult or impossible to come by. You have to look at comps for products in a similar or equal product category, and sometimes they just aren’t available.

Nature versus nurture

One way to think about this is that products have a nature/nurture element to their metrics. Some product categories, like chat or email, are naturally high-frequency. You use them a lot. Other products, like tax software, might give you value but you only use it once per year. A lot of ecommerce products are in-between, where you might buy gadgets every couple months but not every day. Just because people only use your product once a year doesn’t mean you don’t have product/market fit, as long as you’re building a tax product and not chat.

The two extremes are interesting:

- Medical apps: They may have high retention since if you have a chronic ailment, you may constantly be using an app relevant to your condition, but maybe not every day

- Books/Games: You read them nonstop for a few days or a week or two, and then once you’ve consumed the content, you never go back

The point I’ll make on this is that due to the nature of certain product categories, there’s a natural range of DAU/MAUs, +1 day and +1 week retention metrics. That’s the “nature” part of the product category. No matter how good your tax software is, you won’t get people to use it every day.

Based on your product execution though, you can maximize the the metrics within the natural range. A really good news product like Flipboard is able to drive 50%+ DAU/MAUs, which are fantastic.

Some product categories cannot get high DAU/MAUs

One key conclusion of this is that it doesn’t make sense to try to compare against Twitter or Facebook’s 50% DAU/MAU unless you are in the same category as them. A lot of social games target 30% DAU/MAU, but we can also see from the Flurry chart that social games are also amongst the highest DAU/MAU categories.

That said, if you are in the same category, then these rival products really tell you how good your metrics could really be, if you executed them in the right way.

Either way, don’t fight your nature :)

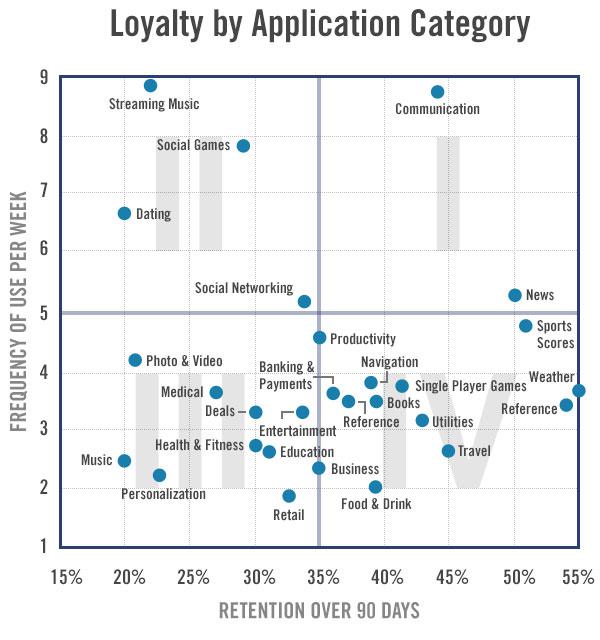

Update: New chart from Flurry

A while after I wrote this, Flurry released a new version of their chart, which you can see below. Full article here. It’s interesting to see which categories have shifted a bit, I imagine because the number of new apps in each category has changed a lot.

No, you don’t need a real-time data dashboard by Mike Greenfield

My friend Mike Greenfield recently started blogging, and I couldn’t recommend his blog Numerate Choir more. I also had him on my list of growth hackers from a month ago. Mike is (as of today) 500 Startups’s first “Growth Hacker in Residence” and before that, co-founded Circle of Moms (acquired by Sugar), and was a data geek at Linkedin and Paypal.

My friend Mike Greenfield recently started blogging, and I couldn’t recommend his blog Numerate Choir more. I also had him on my list of growth hackers from a month ago. Mike is (as of today) 500 Startups’s first “Growth Hacker in Residence” and before that, co-founded Circle of Moms (acquired by Sugar), and was a data geek at Linkedin and Paypal.

Some of his excellent recent blog posts:

- Why “A/B Testing vs. Holistic UX Design” Is a False Dichotomy

- Cutting the Facebook cord

- The Visionary and the Pivoter

And with his permission, I’ve cross-posted one of his recent essays below.

Enjoy!

No, you don’t need a real-time data dashboard*

By Mike Greenfield

Originally posted on Numerate Choir

When Circle of Friends started to grow really quickly in 2007, it was really tough for Ephraim and me to stay focused.

Many times over the course of a the day, Ephraim would turn and ask me how many signups we’d had in the last ten minutes. That might have been annoying, but for the fact that I was just as curious: I’d just run the query and had an immediate answer.

Rapid viral growth can be unbelievably addictive for the people who are working to propagate it. You tweaked a key part of your flow and you want to see what kind of impact it’s having — right now. You’ve added more users in the last hour than you’ve ever added in an hour before, and you wonder if the next hour will be even better.

That addictiveness can be a great asset to growth hackers; I’d argue that anyone who doesn’t have that sort of jittery restlessness probably wouldn’t be the right fit in a growth hacking role. Restlessness is a huge motivator: I want to grow the user base, so I’m going to implement this feature and push it out as quickly as possible just so I can see what impact it will have. And if this feature doesn’t work, I’m going to try and get something else out before I leave the office so I can see if I’ve uncovered something else before it’s time to go to bed.

One day, I came up with a feature idea as I was walking to the train station in the morning. I coded it up and pushed it out while on the 35 minute train ride. There was a ten minute walk from the train station to my office; by the time I got to the office I saw that my feature was increasing invitations by around 20%.

I loved telling that story to potential engineering hires.

Here’s the thing, though: if everyone in your company behaves like that, you may acquire a huge user base, but you’ll likely never build anything of long-term value. You’ll wind up optimizing purely for short-term performance, never moving toward a strong vision

Back during that Circle of Friends growth period, I decided to automate an hourly stats email to Ephraim and myself. It satisfied our curiosity about how things were growing right now, but it stopped me from running SQL queries every five minutes. At least in theory, that meant we were focused on real work for 58 minutes every hour. In retrospect, it seems ridiculous that we needed stats updates every sixty minutes, but that actually was an improvement.

My distracted experience is why I worry about the effect of analytics companies that now promote a real-time dashboard as an awesome new feature.

It’s technically impressive that they’ve implemented real-time functionality. And at first glance, it’s very cool that I as a user can log in mid-day and see how stats are trending.

But the key distinction — and about 60% of analytics questions I’ve seen people ask over the years are on the wrong side — is if you’re looking at stats now because you’re curious and impatient, or because those stats will actually drive business decisions.

I’m afraid that in most cases, real-time stats are being used by people who aren’t iterating as quickly as growth hackers. The “need” for stats is driven more by curiosity and impatience than by decision-making.

Execs who are making big picture decisions are probably better served by looking at data less frequently. Growth hackers and IT ops types can and should attack problems restlessly — a big part of their job is optimizing everything for the immediate future. But executives are best-served waiting (perhaps until the end of the week), so they can take a long, deep look at the data and think more strategically.

Pitch the future while building for now

On the eve of the 500 Startups demo day, I wanted to offer some thoughts on pitching versus product planning. In an effort to impress investors, we’ve all steered our products towards what we think is sexy or investable, versus what is most likely to work for consumers. I’ve come to believe that this is a kind of Silicon Valley disease, and we should try hard to avoid it.

The short-term/long-term dilemma

One of the hardest things for entrepreneurs is the struggle between two things:

- Having a really big, really abstract goal for the future (“Connect everyone in the world!”, “Sell all the things!”)

- Picking the headline on the landing page for current product you have (“Sign up for this college social network”, “Buy these books”)

It can be easy to confuse the role of the two.

Two failure cases:

If you let your big abstract goal take over day to day product development, then I’m convinced that you’ll end up building a really weird product. Consumers don’t care about your long-term strategy, they just want to scratch their itch now. They want to put you in a bucket with something else they recognize, and if they don’t get it, they’ll hit the back button in 5 seconds flat.

If you let your current product become the whole thing, then you’ll find it hard to recruit a team and find investors. They’ll think you’re just working on a toy, and especially if you don’t have breakout traction, you might get starved for money and talent.

So what’s the right balance?

I’ve come to believe that leading with the day-to-day product is definitely the way to go. Build a great product, even if it looks/sounds like a toy, and get the retention and engagement you need. Once you have that, make the big-picture story work.

That way, you’re focused on the most important thing- getting to product/market fit. That’s the hard part – making up a cool story is easy once you have some numbers.

So focus on the now, and build a great initial product for your customers. Then talk to someone who’s pitched to investors multiple times, and come up with a big, audacious story to wrap around that traction. I guarantee that’ll be easier than you think.

Strive for great products, whether by copying, inventing, or reinventing

This last weekend, I watched Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview (It’s available on iTunes for $3.99 rental). It’s great for many, many reasons, and I wanted to write an important point I seized upon during the talk. Here’s the link, if you want to watch it yourself.

Let’s start with an important quote:

“Insanely great”

That phrase is one of the most confusing things about the Apple philosophy, and I think it is commonly misinterpreted. Product designers often use it as an excuse to endlessly work on their product, with no release date or eye on costs. It becomes the reason why people want to focus on building completely new products and avoid copying competitors.

Apple has done a lot of stealing and reinventing

Yet in the interview, Steve Jobs has lots of interesting anecdotes:

- Apple copying the graphical user interface from Xerox PARC

- The famous quote, “Great artists steal.”

- How NeXT was building web products, same as everyone else

He says all of this, while at the same time criticizing others for lack of taste and insulting their product quality.

Great products, regardless of source

To me, the way to reconcile this is that Steve Jobs cares first and foremost about great products. Sometimes the way to get there was to steal. Sometimes you reinvent and reimagine. And sometimes, you have to invent.

The point is, building a great product is about curating from the entire space of possible features you could build. Shamelessly steal ideas when they are the best ones. Ignore bad ideas even if they’re commonplace. Don’t think you have to build something totally different to make a great product.

I think this has matched with Apple’s strategy towards their most recent generation of products – though they didn’t invent the GUI, the mouse, the MP3 player, downloadable music, the laptop, or the smartphone, they’ve build some of the best products out there. (I’ll give them a lot of great for the iPad though, which is truly a new invention)

The craving for novelty in Silicon Valley

So for all the product managers and designers out there – if you are finding yourself wanting to do it differently just because, or trying to find novel solutions just because, then maybe your priorities are not in order. The goal of building great products is for you to deliver something great to the customer, not to impress your designer friends on what new layout or interaction you’ve just developed.

Make it insanely great, even while you copy, steal, reinvent, or invent whatever you need to make that happen.

Anyway, it’s a great interview and I think everyone involved in tech products should watch it.

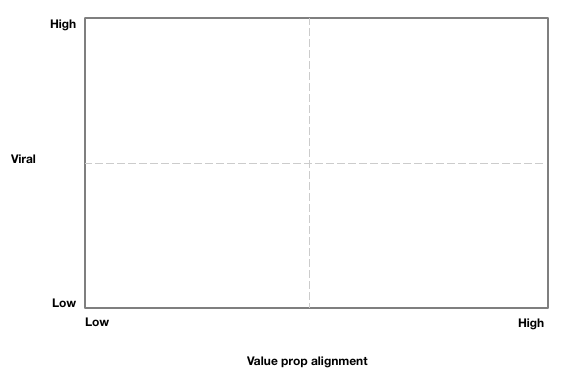

How do I balance user satisfaction versus virality?

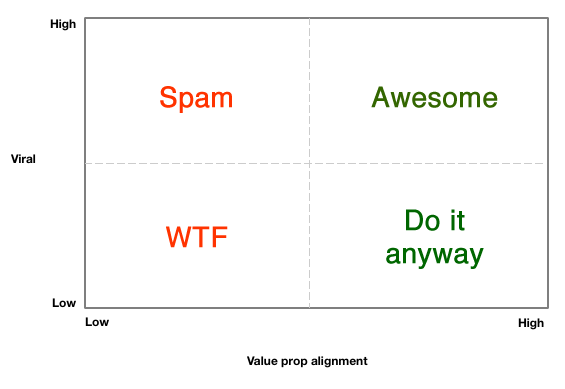

Originally asked on Quora. If you find yourself mostly thinking about balancing satisfaction versus virality, you’re probably doing it wrong. The Quora question is a false dilemma, because it asks you to choose between satisfaction and virality, and then quantifying the tradeoff. Most of the time, if you’re working on naturally viral products, you spend most of your time elsewhere. The world of product decisions is more like:

That is, you have features in your product that either drive growth or don’t, and you have features in your product that either really help the value proposition, or don’t. These are actually pretty independent factors and you can build product features that hit each different quadrant. For example, if you are building a product like Skype, finding your friends and sending invites is clearly a high value prop, high virality action. After all, you can’t use Skype by yourself. But if you take the exact same feature, and try to bolt it onto a non-viral product like, say, a travel search engine, then you’re just creating spam. There’s really no great reason to “find friends” in a travel product, though it might be useful to share your itinerary. A feature that’s high-value in one product is spam in the other. And if you think about each quadrant, you get something like this:  Let’s talk about each bucket:

Let’s talk about each bucket:

- Awesome features grow your product and also people love them. The Skype “find friends” feature is a great one, but so is Quora’s “share to Twitter” feature. After I write this post, I want people to comment and upvote, so something that lets me publish to my audience, which is both viral and part of the value prop is awesome.

- Do it anyway features are just the core of your UX. Writing on walls on Facebook may not be inherently viral in themselves, but it’s important to the product experience, keeps people coming back, and indirectly helps drive the virality of the product. The more people you have coming back, the more changes you have for them to create content or invite people

- Spam features are high virality actions that your users don’t really want to do, and don’t add to the product value prop. I think this is the bucket that the tradeoff lives of a question like, “should I be viral, or offer a great product?” If you are spending a lot of time in this quadrant, then you are shaky ground.

- WTF needs no explanation

Ideally, you want to pick a proven product category that’s naturally viral and high-retention, for instance communication, publishing, payments, photos, etc. – and then spend as much time building awesome features that both drive growth and also make your users happy. Stay away from spam features as much as you can, or use them sparingly lest your product becomes spam.

What does a growth team work on day-to-day?

[UPDATE: I have taken a much longer and more comprehensive whack at this problem in this deck:

How to build a growth team (50 slides)

Here, I answer a couple important questions:

- Why create a growth team?

- What’s the difference between a “growth hacker” and a growth team?

- What’s the difference between growth and marketing/product/whatever?

- Where should growth teams focus?

- I’m starting or joining a growth team! What should I expect?

Hope you enjoy it!

And for the previous answer, which I typed up on Quora some time ago, you can read below.]

So what does a growth team work on day to day? I would break down what a growth team does into two major buckets:

1) Planning/modeling

2) Growth tests.

Let’s dive in, but starting with the usual caveat – you need a killer product before you should start working on growth.

But first, you need a great product

Let me note that if people aren’t using your product, then you’re wasting your time spending too much time optimizing growth. You need a base of users who are happy and then your job is to scale it.

With that caveat in mind, let’s start with the planning activities:

Planning and model building

The planning/modeling side of things is really about understanding, “Why does growth happen?” Every product is different.

- You might find that people find you via SEO and then turn into users that are retained via emails

- You might find that people come to your site via web and then cross-pollinate to mobile, and that’s the key to your growth.

- You might find you need to get them to follow a certain # of people.

- You might realize they need to clip a certain # of links to get started.

These are all things that are product-specific, so I can’t give specific advice in this answer, but this is the foundation for understanding why your product grows. You can come up with a model by looking at your flows for how users come into the site, by talking to users, and by understanding similar products. You can look at successful users and unsuccessful ones.

Once you have a good model, you can create more specific criteria in evaluating the outcome of a good or bad growth project. Your mental model doesn’t have to be perfect at first- the goal is just to get started. As you execute your project successfully, if your growth goes up, then your confidence will grow. (Or you’ll have to revisit things if you keep improving that one metric significantly but overall signups doesn’t go up)

At a more tactical level, eventually this model gets more fine-grained and you can start thinking about individual things that you can change to increase overall growth. Ideally you can model a lot of this in a spreadsheet so you can do scenario-planning around what works and what doesn’t.

The goal is to create some kind of feedback loop that results in sustained growth. Maybe you buy ads, make money, and then reinvest even more in ads. Maybe you get people to create content, driving SEO, which brings in more people that create content. Or maybe you have something invitation based. The important part is to model this process and its component parts.

Project execution

Once you have a model for how to drive your growth, the next part is to actually come up with a bunch of project ideas that can make those numbers go up and to the right. Ideally you can do lots of A/B tests for pretty short ideas that prove out the concept. If it works out, then keep investing.

For something like this, you’ll need a bit of A/B testing infrastructure, a lot of creativity, and some dedicated engineers to get the tests out there.

Because the majority of A/B tests don’t do what you want (maybe the number is <30%) as a result, you’ll want to have many, many A/B tests going at the same time so that you get a couple winners every week. Sometimes people do 1-2 A/B tests per week and then complain that it doesn’t work for them – they probably need to 5-10X their A/B test output in order to get a win or two per week.

To execute each growth project, you may also need to develop some instrumentation around tracking where users come from, and what they do. This can be a bunch of SQL databases and reporting at first, but might move to something fancier later on.

Eventually, the results of these tactical projects feed back into the uber model – you have to constantly reevaluate your priorities and understand which places in the product are the most leveraged in driving growth. So there’s a feedback loop of jumping from the strategic to the tactical, and back.

Summary

To summarize the above:

- Have a solid product where your users are happy

- Coming up with a model for how your site grows

- Trying out ideas and deploying them as A/B tests

- If the site grows, then try out more ideas. If it doesn’t, rethink the model in step 1 because it might be broken

Hope that helps.

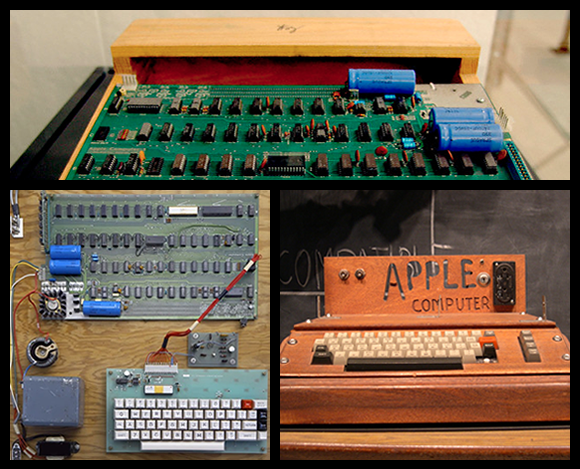

Apple’s Minimum Viable Product

I always hate when designers talk about how Steve Jobs is so amazing and how he’d never settle for anything but the best, blah blah blah. Yes, that’s true, but they’ve been a public company since 1980, they’ve had billions of dollars and 1000s of amazingly talented people on their team.

Before the IPO, at the very beginning when it was just the founders, their first product was the following:

The Apple I, Apple’s first product, was sold as an assembled circuit board and lacked basic features such as a keyboard, monitor, and case. The owner of this unit added a keyboard and a wooden case.

It was a motherboard. Not even a computer- just a motherboard.

I think it’s important to remember when we’re all trying to start something from scratch that you have to start at zero, and the first product will probably suck. It’ll be a motherboard, when what you really wanted to build was an all-aluminum Macbook Air with a Retina display.

But you gotta start somewhere.

Quora: When does high growth not imply product/market fit?

Answered originally on Quora here.

Question: For online/mobile consumer services, in what scenarios does high organic user growth not imply product-market fit?

There’s been a bunch of recent examples of products that grow quickly but have little to no retention/engagement.

The reason is that in this context, you can think of products as having 2 main components:

- Distribution tactics: This is the viral loop – the flow within the site that generates invites, embeds, links, or otherwise exposes new users to the product. Example, for Skype, you can through to a process of inviting and build your addressbook – this generates invites.

- Product experience: The actual usage patterns of the product. For Skype, that’s chatting or talking over VOIP.

In the case of Skype, the viral loop easily flows into the product experience – as a result, you have a nice product that’s both viral and engaging. This is the good case.

Let’s talk about the dysfunctional cases though:

Viral design patterns that don’t make sense for a product

Sometimes though, you end up with a viral loop that’s pretty different/weird compared to the core product experience. For example, there’s a few design patterns that have been viral in the past:

- Filling out a quiz and comparing yourself to others

- Sending a gift or a poke to a bunch of people and then asking the recipient to poke/gift back

- Finding friends and sending invites

- Getting a notification saying that someone has a crush on you and making you fill out email addresses to guess the crush – these emails then generate the next batch of notifications

- … and newer patterns like the Social Reader design pattern on Facebook, or something like spammy low-quality SEO content, which isn’t viral but is the same kind of idea.

(Note these are less effective these days since they’ve been played out – I write about the idea of people becoming desensitized to marketing here)

Because finding a really effective, working viral loop can be rare, sometimes people build a viral loop and then bolt a product onto it. This can be done in a haphazard way that shows a lot of top-line growth but fails on retention/engagement.

Disjointed viral + product experiences

The problem that sometimes, after completing the viral actions, the experience of then using the product is too disjointed, and users bounce right away. For example, you couldn’t put a “find your friends” invitation system in front of a search engine. It doesn’t make any sense. Search engines aren’t social.

The way you could validate this was happening is just to look at the underlying stats past the top-line growth:

- After signing up, how many users are active the next day? Or the next week?

- How many users bounce after the initial viral flow?

- How aggressive is the viral loop, and do you allow the user to understand and experience the underlying product?

- How well does the viral loop communicate that it’s part of a larger, deeper product?

- Does the viral loop makes sense within the context of the product? Does completing the viral loop make the resulting product experience better?

I would look at any new product and ask the above questions to understand what’s going on. In the success case, you have a lot of retention and engagement, and the more viral the product, the stickier it gets. And ideally the design of the viral loop is very “honest” as to how it fits into the rest of the products.

War of the platforms: Facebook, Apple, Android, Twitter.

For the first time in decades, the choice of what platform to build for is not obvious.

Back in the 80s and 90s, it was obvious: Build on Microsoft. Then from 2000 to 2008, the closest thing to a platform was Google, where developers would work with SEO and SEM tactics to get traffic. Then all of a sudden, the Facebook platform got big- really big. Then came mobile.

The last time this happened was in early 1980s

All of a sudden, you can actually pick and choose what platform to actually build upon. Weird. This is a historic event – the last time there were this many choices, we were choosing between Windows, OS/2, or the original Mac.

For those with deep pockets, of course you can build on all of them – yet if you’re an early startup, you really have to double down on one and go multi-platform as you pick up traction.

Evaluating platforms

To evalute which platform is best, here are some thoughts:

- Which offers access to the most relevant users?

- Which one is the most stable?

- Which platform is most unlikely to build a competing app and try to replace yours?

Apple

Ultimately, I think distribution is where platforms really help. As Apple’s demonstrated, you can make developers learn a whole new programming language, a new technology stack, if you can give them access to millions of users. Contrast that to many generates of Google and Yahoo APIs which allowed for data access, but not distribution – much less useful. The biggest problem with Apple is that their leaderboard system is rapidly filling up with winners and it’s harder to break in.

Facebook

Facebook is much more of a free-for-all, and new apps can break in, but they are pretty unstable and are constantly changing their platform. The plus side is that their constant changes introduce new windows of opportunity for an adventurous developer to jump in.

Twitter

Twitter as a consumer product is so simple, there aren’t many marketing channels to even take advantage of. They don’t have an app store, they don’t have an apps page, and it’s hard to discover. Right now, as a platform Twitter’s not that great.

Android

Android seems like a potentially great platform to develop for, but there’s so much opportunity in the iOS world that most developers have overlooked it. Perhaps it’ll turn into the contrarian bet and we’ll see some Android-first apps succeed. Of course, the fragmentation is a real problem, and there hasn’t been an existence proof of an Android-first app that’s had the same level of traction as, say, Rovio or Instagram.

More platforms upcoming?

Let’s also not count out Windows Mobile, or maybe even a resurgence in native applications as Microsoft and Apple build out their desktop app stores. There’s also interesting emerging companies like Pinterest or Dropbox, which may not be in the 100s of millions of users, but may quickly get there.

I predict that marketing channels will loosen up in the short-term

Lots of interesting choices here – there’s a ton of opportunity and I think we’ll see that the competition between platforms will lead to a loosening of distribution channels. Facebook will hopefully open up a bit more, and provide a bunch more traffic, rather than see all their social gaming developers sucked into mobile, for instance. Will be great to see.

Stop asking “But how will they make money?”

Business models are important, but today they’re commoditized

Let me first state: Business models are important. Of course businesses have to make money, that’s a given. But that’s not my point – my point is:

Business models are a commodity now, so “how will they make money?” isn’t an interesting question. The answers are all obvious.

So when you see the next consumer mobile/internet product with millions of engaged users, let’s stop asking about their business model expecting a clever answer – they’ll have dozens of off-the-shelf solutions to choose from – and instead, let’s start asking about the parts of their business that aren’t commoditized yet. (More on this later)

Outsource your monetization

Between the original dotcom bubble versus now, a lot has changed for consumer internet companies. Thankfully, monetization is now a boring problem to solve because there’s a ton of different options to collect revenue that didn’t exist before:

- There’s 200+ ad networks to plug into

- Payment providers like Paypal, Amazon, Stripe

- “Offer walls” like Trialpay

- Mobile payment solutions like Boku

- … and new services coming out all the time (Kickstarter)

Not only that, consumers know and expect to pay for services, something that was novel back in the late 90s. If you offer some sort of marketplace like Airbnb, they’ll expect a listing fee. If you are making a social game on Facebook, they’ll expect to be able to buy more virtual stuff. They’ll expect to pay $0.99 for an iPhone app.

Contrast this with the dotcom bubble, in which you were creating brand new user behavior as well as building these monetization services in-house. In eBay’s case, people just mailed each other (and eBay) money for their listings. Small websites had to build up ad sales teams in order to get advertising revenue, instead of plugging into ad networks. Building apps for phones involved months of negotiation with carriers to get “on deck.” At my last startup, an ad targeting technology company, we encountered companies like ESPN which had written their own ad servers because they didn’t have off-the-shelf solutions when they first started their website back in the late 1990s.

Let me repeat that: They wrote their own ad server as part of building their news site. And that means they had engineers writing lots of code to support their business model rather than making their product better.

Product experience renaissance

Let’s be thankful that we don’t all have to build an ad server every time our Ruby on Rails app is successful. This lets consumer product companies focus on what they’re best at. Also, building a new website doesn’t require $5M anymore. The number of risks in getting your company off the ground are vastly reduced when you combine cheap server hosting, an open source software stack, and multiple bolt-on revenue streams.

This frees us up to be able to work on what’s really important: Building and marketing great products.

These days, the primary cost for any pre-traction company is the apartment rent of the developers who are coding up the product. The profitability of any post-traction company is just based on how fast the team wants to ramp up headcount. If a team can hit product/market fit, a lot of other problems are taken care of.

The lesson behind Facebook’s $3.7B in revenue

Once upon a time, I was skeptical about Facebook’s business model because they received a mere 0.2 cents in advertising revenue per pageview they generated. In 2006, I calculated that maybe they could generate $15M in revenue per year maximum – a nice business, but not a world-changing one. I wrote about this topic here: Why I doubted Facebook could build a billion dollar business, and what I learned from being horribly wrong.

As I wrote in my post, it turns out I was wrong, and Facebook in fact generated $3.7B in 2011 and will generate more than $5B this year. I was wrong in an interesting way though – it turns out that they didn’t dramatically increase their revenue per pageview, but rather they just grew and grew and grew, to ~1 trillion pageviews/month. My mental model was all wrong.

In fact, we have a lot more experience with advertising and transaction based models. It’s pretty clear that an engaging social website will have 0.1% to 0.5% CTRs on their ads, and net an average $0.50 CPM. If you sell something, or have a freemium site, then you can expect 0.5% to 1% of your active users to convert. There’s lots of benchmarks out there, which I discuss in this older blog post. The point is, if you have the audience, you can find the revenue – it’s getting the big audience that’s the main problem.

The last dotcom bubble conditioned many of us to think about a different world than the one we face today. In 1997, there were a mere ~100M users on the internet, mostly on dialup modems. Let me repeat that: The entire dotcom bubble, with all of its bubbly goodness, was based off of 100M dialup users. Compare that to today, where we have 20X that number, over 2 billion users on broadband and mobile. The graph, courtesy World Bank via Google, is incredible.

The point is, the consumer market has grown by so much that the upside opportunity is tremendous if you get a product exactly right. Given all the growth opportunity, and given the plug-in revenue models, the main bottleneck for building a great company doesn’t seem to be the business model at all.

In fact, the business model seems like a second or third order problem. So again, I argue, let’s stop asking about it.

At over 450 million uniques per month, let’s stop wondering what Twitter’s revenue model will be. Obviously it will be some form of advertising, and maybe they’ll experiment with freemium or transaction fees somehow. You can debate if you think they will ultimately be a $100B company or a $10B one, but let’s skip the conversation on whether or not they’ll fail because they don’t have a business model.

The new question to ask

If you agree with me that business model is no longer a first-order question, then what’s the real question to ask? The thing that makes the business model work is really about getting to the scale where the business model becomes trivial.

Let’s ask a more important question:

Could this product engage and retain 100s of millions of active users?

For the first time ever, hitting 100+ million active users is actually realistic. First off, how incredible is that? In recent years, many startups have done it, such as: Zynga, Facebook, Twitter, Groupon, Linkedin, etc. I think we’ll also see Dropbox, Pandora, and others get there too.

For an early stage company, asking this question is really just a test of the team’s ambition, their initial market, and an evaluation of their product/market fit. Obviously if their product isn’t working, they won’t even be close.

Once a startup has product/market fit and is scaling, then the answer to this question revolves around marketing and technology competence. Also, the product might have to evolve as the initial market gets saturated- like Facebook with college and Twitter with their early adopter audience.

To sum this all up:

- Making money as a business is important, but commoditized

- You can plug into 100s of options for monetizing an audience, if you have one

- We’re working with 20X the internet audience compared to the dotcom bubble, and 1/10 the cost of starting a company

- Facebook is hitting $5B in revenue via sheer growth, not monetization innovation

- You should aim to hit 100 million active users, and get an off-the-shelf monetization solution later

- Evaluate new companies on market size and ability to grow to 100 million actives, rather than monetization methods

Know the difference between data-informed and versus data-driven

Metrics are merely a reflection of the product strategy that you have in place

Data is powerful because it is concrete. For many entrepreneurs, particularly with technical backgrounds, empirical data can trump everything else – best practices, guys with fancy educations and job titles – and for good reason. It’s really the skeptic’s best weapon, and it’s been an important tool in helping startups solve problems in new and innovative ways.

It’s easy to go too far – and that’s the distinction made between “data-informed” versus “data-driven,” which I originally heard at a Facebook talk in 2010 (included underneath the post). Ultimately, metrics are merely a reflection of the product strategy that you already have in place and are limited because they’re based on what you’ve already built, which is based on your current audience and how your current product behaves. Being data-informed means that you acknowledge the fact that you only have a small subset of the information that you need to build a successful product. After all, your product could target other audiences, or have a completely different set of features. Data is generated based on a snapshot based on what you’ve already built, and generally you can change a few variables at a time, but it’s limited.

This means you often know how to iterate towards the local maximum, but you don’t have enough data to understand how to get to the best outcome in the biggest market.

This is a messy problem, don’t let data falsely simplify it

So the difference between data-informed versus data-driven, in my mind, is that you weigh the data as one piece of a messy problem you’re solving with thousands of constantly changing variables. While data is concrete, it is often systematically biased. It’s also not the right tool, because not everything is an optimization problem. And delegating your decision-making to only what you can measure right now often de-prioritizes more important macro aspects of the problem.

Let’s examine a couple ways in which a data-driven approach can lead to weak decision-making.

Data is often systematically biased in ways that are too expensive to fix

The first problem with being data-driven is that the data you can collect is often systematically biased in unfixable ways.

It’s easy to collect data when the following conditions are met:

- You have a lot of traffic/users to collect the data

- You can collect the data quickly

- There are clear metrics for what’s good versus bad

- You can collect data with the product you have (not the one you wish you had)

- It doesn’t cost anything

This type of data is good for stuff like, say, signup %s on homepages. They are often the most trafficked parts of the site, and there’s a clear metric, so you can run an experiment in a few days and get your data back quickly.

In contrast, if you are looking to measure long-retention rates, that’s much more difficult. Or long-term perceptions of your user experience, or trying to measure the impact of an important but niche feature (like account deletion). These are all super difficult because they take a long time, or are expensive, or are impossible datapoints to collect – people don’t want to wait around for a month to see what their +1 month retention looks like.

And yet, oftentimes these metrics are exactly the most important ones to solve.

Worse yet, consider the cases where you take a “data-driven” mindset and try to trade off the metrics between concrete datapoints like signup %s versus long-term retention rates. It’s difficult for retention to ever win out, unless you take a more macro and enlightened perspective on the role of data. Short- vs long-term tradeoffs require deep thinking, not shallow data!

Not everything is an optimization problem

At a more macro level, it’s also important to note that the most important strategic issues are not optimization problems. Let’s start at the beginning, when you’re picking out your product. You could, for example, build a great business targeting consumers or enterprises or SMBs. Similarly, you can build businesses that are web-first (Pinterest!) or mobile-first (Instagram!) and both be successful. These are things where it might be nice to have a feel for some of the general parameters, like market size or mobile growth, but ultimately they are such large markets that it’s important to make the decision where you feel good about it. In these cases, you’re forced to be data-informed but it’s hard to be data-driven.

These types are strategy questions are especially important when the industry is undergoing a disruptive innovation, as discussed in Innovator’s Dilemma. In the book, Clayton Christensen discusses the pattern of companies who are successful and build a big revenue base in one area. They find that it’s almost always easier to increase their core business by 10% than it is to create a new business to do the same, but this thinking eventually leads to their demise. This happened in the tech industry from mainframes vs PCs, hardware vs software, desktop vs web, and web vs mobile now. The incumbents are doing what they think is right- listening to their current customer base, improving revenues from a % basis, and in general trying to do the most data-driven thing. But without a vision for how the industry will evolve and improve, the big guys are eventually disrupted.

Leverage data in the right way

It’s important to leverage data the same way, whether it’s a strategic or tactical issue: Have a vision for what you are trying to do. Use data to validate and help you navigate that vision, and map it down into small enough pieces where you can begin to execute in a data-informed way. Don’t let shallow analysis of data that happens to be cheap/easy/fast to collect nudge you off-course in your entrepreneurial pursuits.

Facebook on data-informed versus data-driven

I leave you with the Facebook video that inspired this post in the first place – presented by Adam Mosseri. He uses the example of multiple photo uploads, and how they use metrics to optimize the workflow. Watch the video embed below or go to YouTube.

What makes Sequoia Capital successful? “Target big markets”

Don Valentine, who founded Sequoia Capital, talks about what makes Sequoia Capital effective. It’s one of my favorite talks, and I find myself watching and re-watching it from time to time, and I’d encourage everyone to hear the wisdom themselves.

Markets, not team

In the beginning of the video, Don Valentine asks, why is Sequoia successful? He says that most VCs talk about how they finance the best and the brightest, but Sequoia focuses instead on the size of the market, the dynamics of the market, and the nature of the competition.

This is, of course, super interesting because in many ways it’s contrarian to the typical response that investing is all about “team.”

Creating markets versus exploiting markets

Another choice quote: “We’re never interested in creating markets – it’s too expensive. We’re interested in exploiting markets early.”

In consumer internet, when the divisions that separate product categories are so fuzzy, it can be hard to understand when you’re creating a market versus when you’re attacking an existing one. My rule of thumb is that:

If people know how to search for products in your category then you are in an existing market.

I’ve written more about this in posts here and here

Watch the video of Don Valentine of Sequoia capital on “Target Big Markets” on YouTube or in the embed below:

How to use Twitter to predict popular blog posts you should write

Using retweets to assess content virality

Recently I’ve been running an experiment:

- Tweet an insight, idea, or quote

- See how many people retweet it

- If it catches, then write a blog post elaborating on the topic

My recent Growth Hacker post was the result of one such tweet, which you can see above in my Crowdbooster dashboard. I wrote it on a whim, but after the retweets, I developed it into a longer and more comprehensive blog post. (Note that sometimes a tweet is not suitable to developed into a blog post, but most of the time this technique works)

Why this works

This works because the headline is key. It spreads the content behind it.

This is especially true on Twitter, but it’s also true for news sites that will pick up and syndicate your content. If that headline is viral and the content behind it is high quality, there’s a multiplier effect – sometimes a difference of 100X or more. Naturally, you want to optimize the flow of how people interact with your content, starting with what they see first: The title.

After all, what’s a better test for whether the following will be viral:

New blog post: Growth Hacker is the new VP Marketing [link]

than the tweet:

Growth Hacker is the new VP marketing

It’s a natural test.

I’ll also argue that if you can express the core of your idea in a short, pithy tweet, then that’s a good test for whether the underlying blog post will be interesting as well. Great tweets are often provocative insights or mesmerizing quotes, and there’s a lot to say by examining the issues more deeply. Contrast this to writing a long, unfocused, laundry-list essay examining a topic from all angles, taking no interesting positions or risks along the way – now that’s a recipe for boredom.

Combining virality with a high-quality product, of course, is the key to a lot of things – not just blogging :)

Don’t waste your time writing what people don’t want to read

Testing your ideas like this allows you to invest more time and effort into the content – a clear win.

Personally, I love writing long-form content that dives deep into an area, and also enjoy reading it as well. Unfortunately, writing a blog post often takes a long time – an hour or more. Use this technique to make it safer to spend more time, think more deeply, and research more broadly on you write. In my experience, writing a high-quality, highly retweetable blog post once per month is better than writing a daily stream of short, low-quality posts that no one will read. Plus, it takes less time.

As a smart guy once said: “Do less, but better.”

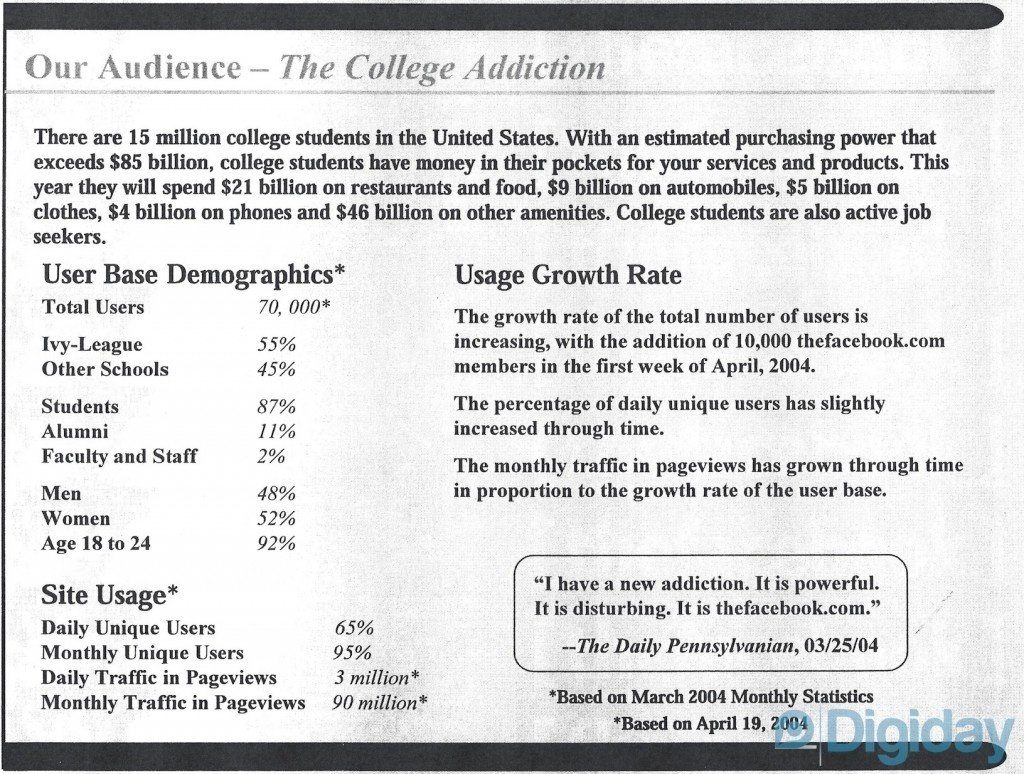

Quora: Has Facebook’s DAU/MAU always been ~50%?

I recently asked, and then answered my own question on Quora and wanted to share here as well.

Has Facebook’s DAU/MAU always been ~50%?

According to public info, Facebook’s DAU/MAU is 58% these days. Here’s a link.

It states:

- 901 million monthly active users at the end of March 2012

- 526 million daily active users on average in March 2012

Has Facebook’s DAU/MAU always been this good, as a consequence of its product category (communication/photo-sharing/etc.)? Or was it once a lot worse and was improved over time?

(UPDATE: Here’s a followup question I have about the same topic- Was Facebook’s DAU/MAU ~50% prior to launching the Newsfeed in 2009?)

Answer: Yes, Facebook’s DAU/MAU has been close to 50%, at least since 2004.

Based on their media kit from 2004, their DAU/MAU was already 75%.

Since this media kit, their DAU/MAU data has been included in their financials since 2009. However, I theorize that Facebook’s DAU/MAU has always been high as a natural outcome of the communication-oriented usage of the product. Contrast this to a product category like ecommerce which you are unlikely to use and purchase with every day.

In their recent financial filings, the following chart is shown for Facebook’s DAU and MAU since 2009:

If you do a graph of the DAU/MAU on this data, since 2009, you’ll see that it starts around 45-47% and goes up to a very impressive 58% recently.

(As an aside, another interesting aspect is that Facebook’s MAU growth looks pretty much like a straight line, and so the % growth has been slowing down as of late. The MAU growth was around 23% starting in 2009, but is now down to 6-7% in recent months. See below for a graph on MAU vs % MAU growth)

How do I learn to be a growth hacker? Work for one of these guys :)

After writing my recent article on Growth Hackers, I’ve been asked by quite a few folks on how to learn the discipline. The best answer is, learn from someone who’s already good at it – if you’re technical and creative, it’s well worth the time.

I would encourage everyone to also read Andy Johns’s Quora answers on What is Facebook’s User Growth team responsible for and what have they launched? and

What are some decisions taken by the “Growth team” at Facebook that helped Facebook reach 500 million users?– it lays out a lot of the key activities used in a well-run growth team.

The list below includes some of these folks I know personally, some just by reputation- but collectively they’ve grown products up to millions, 10s of millions, and in some cases, 100M+ users. Typically they use quantitatively-oriented techniques centered on virality across different channels such as iOS, Facebook, email, etc. There’s lots of iteration, A/B testing, and experimentation involved. There’s also really great growth hackers centered around SEO, SEM/ad arb, and other techniques, but for the most part I’m just listing out the folks around quant-based virality. The important thing about virality is, it’s free :) So it’s an important skill for startups.

Missing from this list are many unsung heroes over at Zynga, Dropbox, Branchout, Viddy/Socialcam, lots of ex-Paypal/Slide people, etc., etc. Also, all of these guys typically have co-founders or entire growth teams around them that are experts, even if I don’t know them by name.

If others in the community would like to make suggestions, tweet me at @andrewchen or just reply in the comments.

| Name | Background | |

| Noah Kagan | AppSumo, Mint, Facebook | noahkagan |

| David King | Blip.me, ex-Lil Green Patch | deekay |

| Mike Greenfield | Circle of Moms, ex LinkedIn | mike_greenfield |

| Ivan Kirigin | Dropbox, ex-Facebook | ikirigin |

| Michael Birch | ex-Bebo, BirthdayAlarm | mickbirch |

| Blake Commegere | ex-Causes/Many games | commagere |

| Ivko Maksimovic | ex-Chainn/Compare People | ivko |

| Dave Zohrob | ex-Hot or Not, MegaTasty | dzohrob |

| Jia Shen | ex-RockYou | metatek |

| James Currier | ex-Tickle | jamescurrier |

| Stan Chudnovsky | ex-Tickle | stan_chudnovsky |

| Siqi Chen | ex-Zynga | blader |

| Ed Baker | esbaker | |

| Alex Schultz | alexschultz | |

| Joe Greenstein | Flixster | joseph77b |

| Yee Lee | yeeguy | |

| Josh Elman | Greylock, ex-Twitter | joshelman |

| Jamie Quint | Lookcraft, ex-Swipely | jamiequint |

| Elliot Shmukler | eshmu | |

| Aatif Awan | aatif_awan | |

| Andy Johns | Quora, Twitter, Facebook | ibringtraffic |

| Robert Cezar Matei | Quora, ex-Zynga | rmatei |

| Nabeel Hyatt | Spark, ex-Zynga | nabeel |

| Paul McKellar | SV Angel, ex-Square | pm |

| Greg Tseng | Tagged | gregtseng |

| Othman Laraki | othman | |

| Akash Garg | Twitter, ex-Hi5 | akashgarg |

| Jonathan Katzman | Yahoo, ex-Xoopit | jkatzman |

| Gustaf Alstromer | Voxer | gustaf |

| Jon Tien | Zynga | jontien |

UPDATE: My friend Dan Martell’s new company, Clarity, provides a way to access experts like this via phone and email. Here’s the directory of folks with expertise on growth.

Growth Hacker is the new VP Marketing

The rise of the Growth Hacker

The new job title of “Growth Hacker” is integrating itself into Silicon Valley’s culture, emphasizing that coding and technical chops are now an essential part of being a great marketer. Growth hackers are a hybrid of marketer and coder, one who looks at the traditional question of “How do I get customers for my product?” and answers with A/B tests, landing pages, viral factor, email deliverability, and Open Graph. On top of this, they layer the discipline of direct marketing, with its emphasis on quantitative measurement, scenario modeling via spreadsheets, and a lot of database queries. If a startup is pre-product/market fit, growth hackers can make sure virality is embedded at the core of a product. After product/market fit, they can help run up the score on what’s already working.

This isn’t just a single role – the entire marketing team is being disrupted. Rather than a VP of Marketing with a bunch of non-technical marketers reporting to them, instead growth hackers are engineers leading teams of engineers. The process of integrating and optimizing your product to a big platform requires a blurring of lines between marketing, product, and engineering, so that they work together to make the product market itself. Projects like email deliverability, page-load times, and Facebook sign-in are no longer technical or design decisions – instead they are offensive weapons to win in the market.

Get updates to this essay, and new writing on growth hacking:

The stakes are huge because of “superplatforms” giving access to 100M+ consumers

These skills are invaluable and can change the trajectory of a new product. For the first time ever, it’s possible for new products to go from zero to 10s of millions users in just a few years. Great examples include Pinterest, Zynga, Groupon, Instagram, Dropbox. New products with incredible traction emerge every week. These products, with millions of users, are built on top of new, open platforms that in turn have hundreds of millions of users – Facebook and Apple in particular. Whereas the web in 1995 consisted of a mere 16 million users on dialup, today over 2 billion people access the internet. On top of these unprecedented numbers, consumers use super-viral communication platforms that rapidly speed up the proliferation of new products – not only is the market bigger, but it moves faster too.

Before this era, the discipline of marketing relied on the only communication channels that could reach 10s of millions of people – newspaper, TV, conferences, and channels like retail stores. To talk to these communication channels, you used people – advertising agencies, PR, keynote speeches, and business development. Today, the traditional communication channels are fragmented and passe. The fastest way to spread your product is by distributing it on a platform using APIs, not MBAs. Business development is now API-centric, not people-centric.

Whereas PR and press used to be the drivers of customer acquisition, instead it’s now a lagging indicator that your Facebook integration is working. The role of the VP of Marketing, long thought to be a non-technical role, is rapidly fading and in its place, a new breed of marketer/coder hybrids have emerged.

Airbnb, a case study

Let’s use case of Airbnb to illustrate this mindset. First, recall The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs:

Over time, all marketing strategies result in shitty clickthrough rates.

The converse of this law is that if you are first-to-market, or just as well, first-to-marketing-channel, you can get strong clickthrough and conversion rates because of novelty and lack of competition. This presents a compelling opportunity for a growth team that knows what they are doing – they can do a reasonably difficult integration into a big platform and expect to achieve an advantage early on.

Airbnb does just this, with a remarkable Craigslist integration. They’ve picked a platform with 10s of millions of users where relatively few automated tools exist, and have created a great experience to share your Airbnb listing. It’s integrated simply and deeply into the product, and is one of the most impressive ad-hoc integrations I’ve seen in years. Certainly a traditional marketer would not have come up with this, or known it was even possible – instead it’d take a marketing-minded engineer to dissect the product and build an integration this smooth.

Here’s how it works at a UI level, and then we’ll dissect the technology bits:

(This screenshots are courtesy of Luke Bornheimer and his wonderful answer on Quora)

Looks simple, right? The impressive part is that this is done with no public Craigslist API! It turns out, you have to look closely and carefully at Craigslist in order to accomplish an integration like this. Note that it’s 100X easier for me to reverse engineer something that’s already working versus coming up with the reference implementation – and for this reason, I’m super impressed with this integration.

Reverse-engineering “Post to Craigslist”

The first thing you have to do is to look at how Craigslist allows users to post to the site. Without an API, you have to write a script that can scrape Craigslist and interact with its forms, to pre-fill all the information you want.

The first thing you can notice from playing around with Craigslist is that when you go to post something, you get a unique URL where all your information is saved. So if you go to https://post.craigslist.org you’ll get redirected to a different URL that looks like https://post.craigslist.org/k/HLjRsQyQ4RGu6gFwMi3iXg/StmM3?s=type. It turns out that this URL is unique, and all information that goes into this listing is associated to this URL and not to your Craigslist cookie. This is different than the way that most sites do it, where a bunch of information is saved in a cookie and/or server-side and then pulled out. This unique way of associating your Craigslist data and the URL means that you can build a bot that visits Craigslist, gets a unique URL, fills in the listing info, and then passes the URL to the user to take the final step of publishing. That becomes the foundation for the integration.

At the same time, the bot needs to know information to deal with all the forms – beyond filling out the Craigslist category, which is simple, you also need to know which geographical region to select. For that, you’d have to visit every Craigslist in every market they serve, and scrape the names and codes for every region. Luckily, you can start with the links in the Craiglist sidepanel – there’s 100s of different versions of Craigslist, it turns out.

If you dig around a little bit you find that certain geographical markets are more detailed than others. In some, like the SF Bay Area, there’s subareas (south bay, peninsula, etc.) and neighborhoods (bernal, pacific heights) whereas in other markets there’s only subareas, or there’s just the market. So you’d have to incorporate all of that into your interface.

Then there’s the problem of the listing itself – by default, Craigslist works by giving you an anonymous email address which you use to communicate to potential customers. If you want to drive them to your site, you’d have to notice that you can turn off showing an email, and just provide the “Contact me here” link instead. Or, you could potentially fill a special email address like listing-29372@domain.com that automatically directs inquiries to the right person, which can be done using services like Mailgun or Sendgrid.

Finally, you’ll want the listing to look good – it turns out Craigslist only supports a limited amount of HTML, so you’ll need to work to make your listings work well within those constraints.

Completing the integration is only the beginning – once it’s up, you’d have to optimize it. What’s the completion % once sometime starts sharing their listing out to Craigslist? How can you change the flow, the call to action, the steps in the form, to increase this %? And similarly, when people land from Craigslist, how do you make sure they are likely to complete a transaction? Do they need special messaging?

Tracking all of this requires additional work with click-tracking with unique URLs, 1×1 GIFs on the Craigslist listing, and many more details.

Long story short, this kind of integration is not trivial. There’s many little details to notice, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the initial integration took some very smart people a lot of time to perfect.

No traditional marketer would have figured this out

Let’s be honest, a traditional marketer would not even be close to imagining the integration above – there’s too many technical details needed for it to happen. As a result, it could only have come out of the mind of an engineer tasked with the problem of acquiring more users from Craigslist. Who knows how much value Airbnb is getting from this integration, but in my book, it’s damn impressive. It taps into a low-competition, huge-volume marketing channel, and builds a marketing function deeply into the product. Best of all, it’s a win-win for everyone involved – both the people renting out their places by tapping into pre-built demand, and for renters, who see much nicer listings with better photos and descriptions.

This is just a case study, but with this type of integration, a new product is able to compete not just on features, but on distribution strategy as well. In this way, two identical products can have 100X different outcomes, just based on how well they integrate into Craigslist/Twitter/Facebook. It’s an amazing time, and a new breed of creative, technical marketers are emerging. Watch this trend.

So to summarize:

- For the first time ever, superplatforms like Facebook and Apple uniquely provide access to 10s of millions of customers

- The discipline of marketing is shifting from people-centric to API-centric activities

- Growth hackers embody the hybrid between marketer and coder needed to thrive in the age of platforms

- Airbnb has an amazing Craigslist integration

Good luck, growth hackers!

Google+ and the curse of instant distribution

I was reading today’s NYT article on Google+’s new redesign and found myself continually puzzled by the key metric Google continues to report as the success of their new social product: Registered Users.

In the very first sentence, Vic Gundotra writes:

More than 170 million people have upgraded to Google+, enjoying new ways to share in Search, Gmail, YouTube and lots of other places.

The use of registered users is a vanity metric, and reflects how easily Google can cross-sell any new product to their core base of 1 billion uniques per month. What it doesn’t reflect, however, is the actual health of the product.

Ultimately, this misalignment of metrics is due to the curse of instant distribution. Because Google can cross-sell whatever products they want against their billion unique users, it’s easy to grade on that effort. Plus it’s a big number, who doesn’t love a big number?

Google+ should be measured on per user metrics

Here’s what metrics are more important instead: Given the Google+ emphasis on Circles and Hangouts, you’d think that the best metrics to use would evaluate the extent to which these more personal and more authentic features are being used. These would include metrics like:

- Shares per user per day (especially utilizing the Circles feature)

- Friends manually added to circles per user per day (not automatically!)

- Minutes of engagement per user per day

Point is, the density and frequency of relationships within small circles ought to matter more than the aggregate counts on the network. As I’ve blogged about before, you use metrics to reflect the strategy you already have in place, and based on the Google+’s focus on authentic circles of friends, you’d think the metrics would focus on the density of friendships and activities, and not the aggregate numbers.

The curse of instant distribution

Every new product for a startup goes through a gauntlet to reach product/market fit, and then traction. In the real world, product quality and the ability to solve a real problem for people ends up correlating with your ability to distribute the product. Google+ is blessed, and cursed, with the ability to sidestep this completely. They are able to onboard hundreds of millions of users without having great product/market fit, and can claim positive metrics without going through the gauntlet of really making their product work.

Adam D’Angelo of Quora (and previously CTO of Facebook) wrote this insightful commentary regarding Google Buzz a while back:

Why have social networks tied to webmail clients failed to gain traction?

Personally I think this is mostly because the social networking products built by webmail teams haven’t been very good. Even Google Buzz, which is way ahead of the attempts built into Yahoo Mail and Hotmail, has serious problems: the connections inside it aren’t meaningful, profiles and photos are second class, comments bump items to the top of the feed meaning there’s old stuff endlessly getting recycled, and the whole product itself is a secondary feature accessible only through a click below the inbox, which hasn’t gotten it enough distribution to kick off and sustain conversations.I’m pretty sure that if Google, Microsoft, or Yahoo had cloned Facebook almost exactly (friends, profiles, news feed, photos) and integrated it well into their webmail product, that it could have taken off (before Facebook got to its current scale; at this point it will be hard for any competitor, even with a massive distribution channel pushing it).

So I think this question is really, why are social networks that webmail teams build always bad? Here’s my guess:

- The team building the social network knows that they’re going to get a huge amount of distribution via the integration and so they aren’t focused on growth and making a product that people will visit on their own.

- Integrating any two big products is really hard.

- Any big webmail provider is going to have a big organization behind it, and lots of politics and compromises probably make it difficult to execute well.

- Teams that work on webmail products have gotten good at building a webmail product, and haven’t selected for the skills and culture that a team that grows around building a social network will have.

(The bolding is from me). I couldn’t agree more with this answer. I think a key lesson behind the recent success of products like Instagram and Pinterest is that there’s still a lot of room in the market for great social products to take off- but the emphasis has to be on the product rather than the superficial act of onboarding a lot of new users into Google+.

Ultimately, it comes down to how realistic the Google+ folks are in looking at their metrics. If they drink their own kool-aid and think they have product/market fit when it’s in fact the traction is solely dependent on the power of their distribution channels, they may never get their product working.

On the other hand, if they have a balanced view on their metrics and know they don’t have product/market fit yet, then they have a fighting chance. Unfortunately, I think the changes they’ve made to the product recently are more efforts to optimize, rather than fundamental improvements to the product. I think Google+ needs much bigger changes to make it as engaging as the best social products.

The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs

The first banner ad ever, on HotWired in 1994, debuted with a clickthrough rate of 78% (thanks @ottotimmons)

First it works, and then it doesn’t

After months of iterating on different marketing strategies, you finally find something that works. However, the moment you start to scale it, the effectiveness of your marketing grinds to a halt. Sound familiar?

Welcome to the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs:

Over time, all marketing strategies result in shitty clickthrough rates.

Here’s a real example – let’s compare the average clickthrough rates of banner ads when debuted on HotWired in 1994 versus Facebook in 2011:

- HotWired CTR, 1994: 78%

- Facebook CTR, 2011: 0.05%

That’s a 1500X difference. While there are many factors that influence this difference, the basic premise is sound – the clickthrough rates of banner ads, email invites, and many other marketing channels on the web have decayed every year since they were invented.

Here’s another channel, which is email open rates over time, according to eMarketer:

While this graph shows a decline, the other graph (which I don’t have handy) is that the number of emails sent out has increased up to 30+ billion per day.

All these channels are decaying over time, and what’s saving us is the new marketing channels are constantly getting unveiled, too. These new channels offer high performance, because of a lack of competition, big opportunities for novel marketing techniques, and these days, the cutting edge is about optimizing your mobile notifications, not your banner placements.

There are a few drivers for the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs, and here’s a summary of the top ones:

- Customers respond to novelty, which inevitably fades

- First-to-market never lasts

- More scale means less qualified customers

Novelty

Without a doubt, one of the key drivers of engagement for marketing is that customers respond to novelty. When HotWired showed banner ads for the first time in history, people clicked just to check out the experience. Same for being the first web product to email people invites to a website – it works for a while, until your customers get used to the effect, and start ignoring it.