[The topic of setting goals, especially quantitative ones, is a really important topic for any team and any startup. A common format has been the OKR, or “Objectives and Key results” which is in use at Google, Zynga, and many other companies. It consists of setting an objective, and also a series of measurable results aligned with that objective. My good friend Kenton Kivestu, (now Flurry but previously Zynga and Google) has experienced this framework first hand and had a lot of insightful stuff to say about it. You can follow Kenton on Twitter and read his blog here. -Andrew]

Kenton Kivestu, Flurry:

How to set & achieve meaningful OKRs

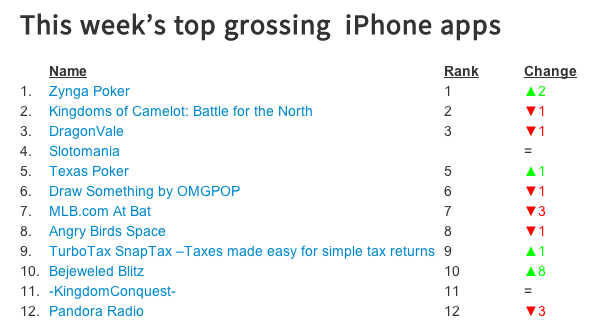

In 2011, when I joined Zynga to work on the mobile poker franchise, we were getting trounced by a competitor named Texas Poker. Their UX was better. They were smoking us on appstore top grossing rankings. And they had 5x the features (not to mention a “premium” pro version of the game they’d just launched). For a company who unequivocally dominated the poker space on FB, our position in the mobile poker market was borderline comical.

The team set an OKR to take the throne: become the #1 top grossing iOS poker game. And then something incredible happened, we did (~6 months later). In my career, I’ve seen many an OKR go haywire (both at Google and Zynga) so this post is my attempt to distill & isolate the common traits I’ve seen in good implementations of an OKR.

First, what is an OKR and why bother?

Google has used OKRs since 1999 at the urging of KPCB partner John Doerr and Rick Klau (former Googler, now Google Ventures partner) has a good post on what is an OKR is (and it’s history). And you can read up on them at Quora too. But the TL;DR is an OKR is a stated goal, known to the whole company and has a pre-defined rubric to measure your success in achieving it.

Whether your at a start-up or big co, the only thing in endless supply is constraints. Time, developer resources, energy and the list goes on. And in a resource constrained world, the best plan of attack is to marshall resources and focus efforts on the best leverage point.

Now the question is, how do you set good OKRs? Like all things, there are many ways to successfully skin a cat but the 3 most common traits I’ve seen in teams that have set and achieved awesome results with OKRs are these:

Measurable

Contrary to popular belief, this doesn’t mean the the OKR needs to be explicitly quantitative (eg drive X% increase in sign-ups or Y% year over year growth in recurring revenues), although it’s fine if that is the case. But it definitely needs to be measurable in the sense that the team can unequivocally evaluate their progress at the end of the OKR period.

For us, the iOS app store Top Grossing rankings were our measuring stick (for better or worse). There was no fudging the numbers and it was dead simple to measure, we were either ahead or behind.

Focused

OKRs are like money. Mo’ money, mo’ problems. The surest way to negate any positive impact from a good OKR is to set 10 good OKRs. It can seem alluring at first – “we’ll accomplish so many things this quarter/year!” – but it will backfire. There is little doubt that 10 good OKRs is worse than nothing. Your team will be torn between competing priorities – should John the engineer work on X or Y this sprint? One will get us closer to OKR A and the other toward OKR B. Inevitably this leads to prioritizing OKRs – this might work if you have 1 or 2 but anymore than that is going to be a recipe for a wasted quarter.

For us, we had 1. If a feature/chunk of work didn’t directly contribute to us climbing the iOS top grossing rankings, it was de-prioritized. As a result, we got a late start on expanding to other platforms (Android tablets, Kindle Fires). That was painful but the focus brought the right end result, since the iOS Top Grossing “pot o’ gold” was orders of magnitude more rewarding than early adoption of Fire or And tablets.

Worth doing

Again, this seems obvious but is worth stating. A good sanity test is ask yourself, “If the company were a person, would it put the successful completion of this OKR on its resume?” If the answer is no, boot it. All too often well-intentioned but “empty” OKRs end up dictating resource allocation. These culprit OKRs typically rise out of a discussion around some product tactics (eg let’s reduce friction in the sign-up flow by X%).

Ok, but OKRs stunt our creativity

An oft argued counterpoint is that OKRs will stunt creativity and the team’s ability to tinker and meander into some great discovery. Defenders of this theory highlight examples of accidental discoveries leading to huge innovations – but this is missing the point. OKRs don’t preclude accidental discoveries, they simply make sure that in absence of a brilliant accident the team is on track to do something else meaningful.

If you’re finding your team sets quarterly OKRs only to trash them each quarter given a brilliant mid-quarter discovery, you’re either:

- a 2-sigma team that repeatedly launches industry leading core features every quarter despite not initially planning them

- setting OKRs not “worth doing” as evidenced by repeated willingness to ditch them

- unfocused and need more operational discipline

In conclusion

OKRs are not a panacea. And they can lead a team astray if they don’t keep them focused, measurable and meaningful. But the flip side is that a well-set OKR can generate a 10x result. OKRs can drive focus and relentless execution, and in turn, those drive incredible results.