The Podcast Ecosystem in 2019 – a16z’s 68 page analysis

Dear readers,

Podcasting has been a slow burn, and has turned into a movement. 90 million Americans now listen to podcasts, and if your behavior is anything like mine, it’s turned into a multi-hour per week habit. I reach for my podcasts whenever I’m commuting, whenever I’m doing a long walk between offices, or if I’m doing random stuff around the house. No wonder the consumer investment team ended up digging into this trend by doing a market map report — the analysis led by Li Jin, Avery Segal and Bennett Carroccio, including work from myself, Connie Chan, and others.

See below for a long-form analysis everything we’ve observed in the podcasting industry. It was originally published on a16z.com. There’s a lot to read here, but I wanted to highlight a couple of my takeaways and what I’m looking for now:

- Podcasting is big, mainstream, but severely undermonetized — and some of the biggest opportunities in the podcasting space lay in pivoting the business model from ads into some kind of direct payment. I’m looking for startups that can change the game there.

- The bigger idea is actually “audio”, not specifically podcasting. And in fact, the combined revenue of Headspace and Calm are more than half of the entire podcasting market. Whoa! I’d be interested in other products that tap into the trends around AirPods, Alexa, voice assistants, etc., but may not directly sound like podcasting

- After this analysis, I’m looking for really differentiated verticals of audio. Meditation is one, but what about something that’s at a much higher price point? For example, something that’s very business-focused and can be put on a corporate credit card? It could create a strong advantage around paid marketing if a product has high subscription retention or ARPU, allowing them to make higher bids in the various ad networks.

The report covers things in more detail at the end, but that’s the tldr; from an investment standpoint.

The other quick plug I want to give — get a copy of the PDF version of the deck by joining the a16z newsletter:

Subscribe to the a16z newsletter here.

The a16z team uses the newsletter to circulate resources, including podcasts, op-eds, presentations, and more. You can subscribe to get more updates.

Without further adieu, here’s the a16z consumer team’s definitive analysis of the podcast ecosystem in 2019. Enjoy!

Thanks,

Andrew

The Podcast Ecosystem in 2019

By Li Jin, Avery Segal, and Bennett Carroccio

In the world of podcasting, the flywheel is spinning: new technologies including AirPods, connected cars, and smart speakers have made it much easier for consumers to listen to audio content, which in turn creates more revenue and financial opportunity for creators, which further encourages high-quality audio content to flow into the space. There are now over 700K free podcasts available and thousands more launching each week.

As new tech platforms hit scale, we on the consumer team have been closely watching the future of media and the technology driving it — in all forms. We’re interested in investing in the next wave of consumer products and startups coming into the ecosystem, and that includes the audio ecosystem.

Our investment philosophy is to not be too prescriptive, so we do the kind of “market map” overview below to help us have a “prepared mind” when we see new startups in the space. The below deck and commentary (with some sections redacted, of course) was presented to the extended consumer team, including general partners Connie Chan and Andrew Chen, who are investing in this space. If you’re working on anything interesting in this area, we’d love to hear from you!

From niche internet community to one-third of Americans

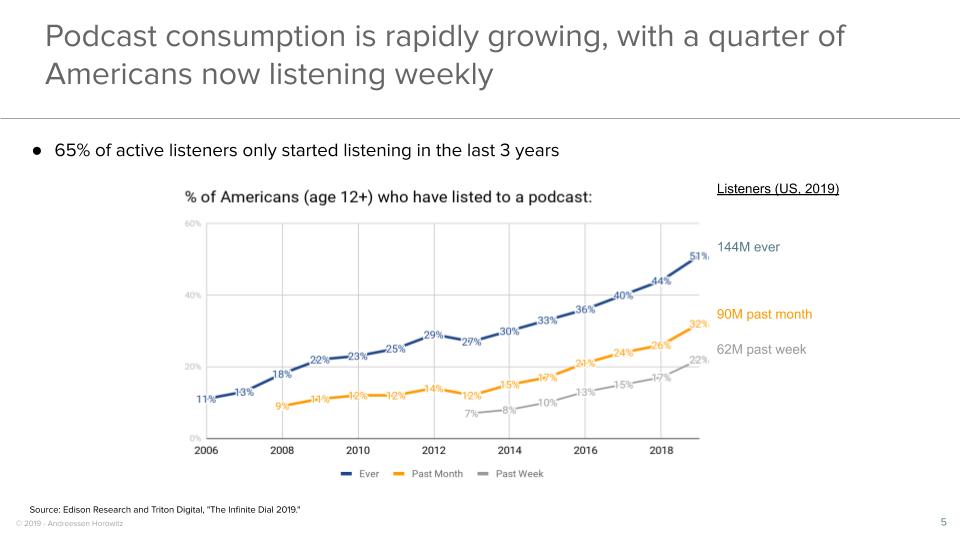

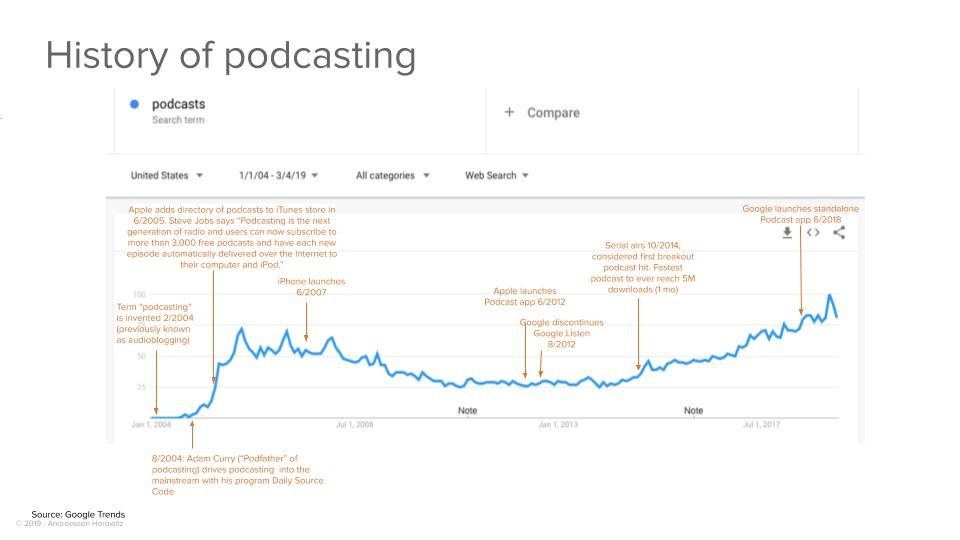

Over the course of the last 10 years, podcasts have steadily grown from a niche community of audiobloggers distributing files over the internet, to one-third of Americans now listening monthly and a quarter listening weekly.

Americans listening weekly to podcasts grew from 7% in 2013 to 22% in 2019. 65% of monthly podcast listeners have been listening for less than 3 years.

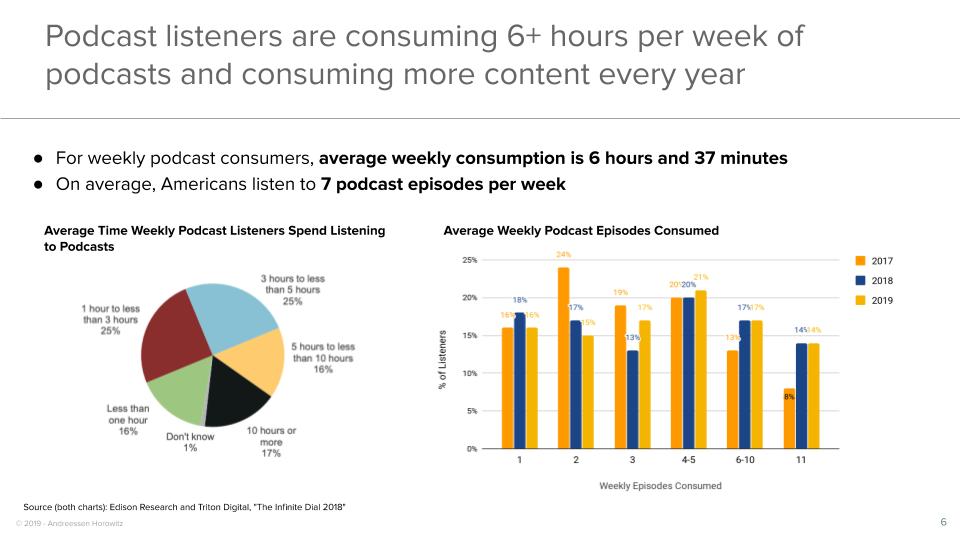

People are already spending a lot of time on podcasts, and it’s growing: listeners are consuming 6+ hours per week and consuming more content every year.

Among weekly podcast listeners, there’s high consumption: 7 episodes per week and nearly 1 hour per day.

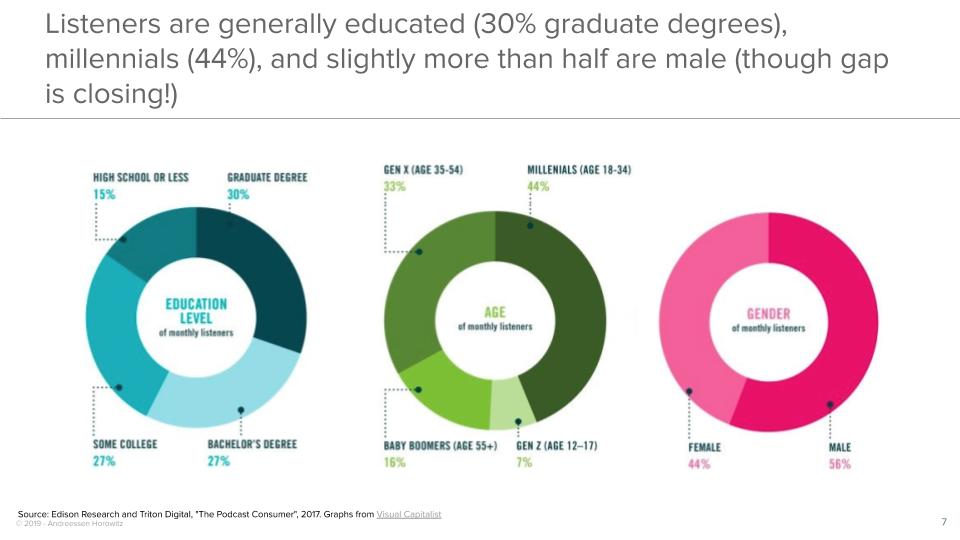

The demographic of podcast listeners is not your average American. Roughly half of podcast listeners make $75,000 or more in annual income; a majority have a post-secondary degree; and almost one-third have a graduate degree [source]. There’s also a gender gap with podcast listeners skewing mostly male, mirroring the gap among podcast creators as well. However, the gender gap has narrowed from a 25% gap in 2008 to 9% today.

Podcast listeners are not your typical American: they’re affluent, highly educated, and skew male.

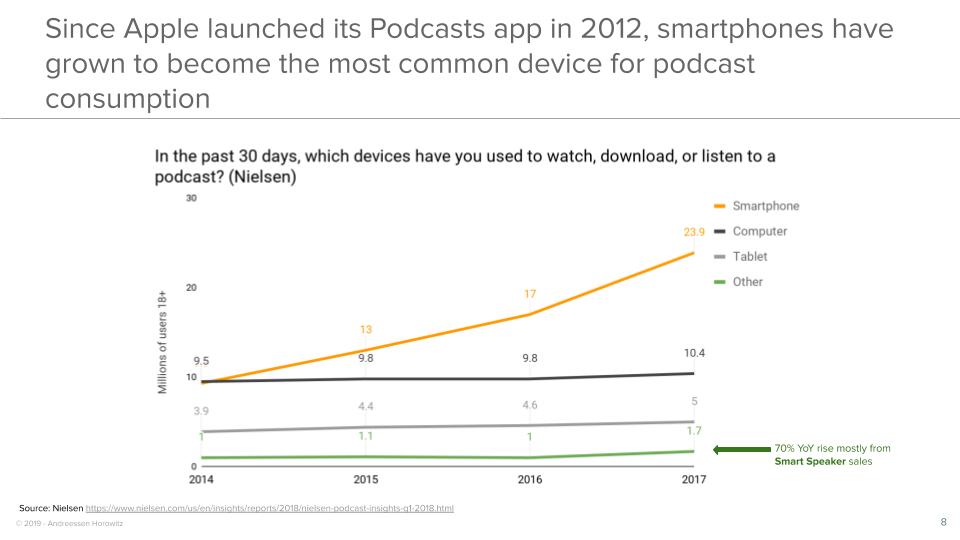

In the years following the release of Apple’s podcast app in 2012, smartphones pulled ahead of computers for podcast consumption and have grown to become the dominant way that consumers listen to podcasts. The green line includes smart speakers, which have grown 70% year over year in terms of listening.

Since Apple launched its Podcasts app in 2012, smartphones have quickly grown to become the most common device for podcast consumption.

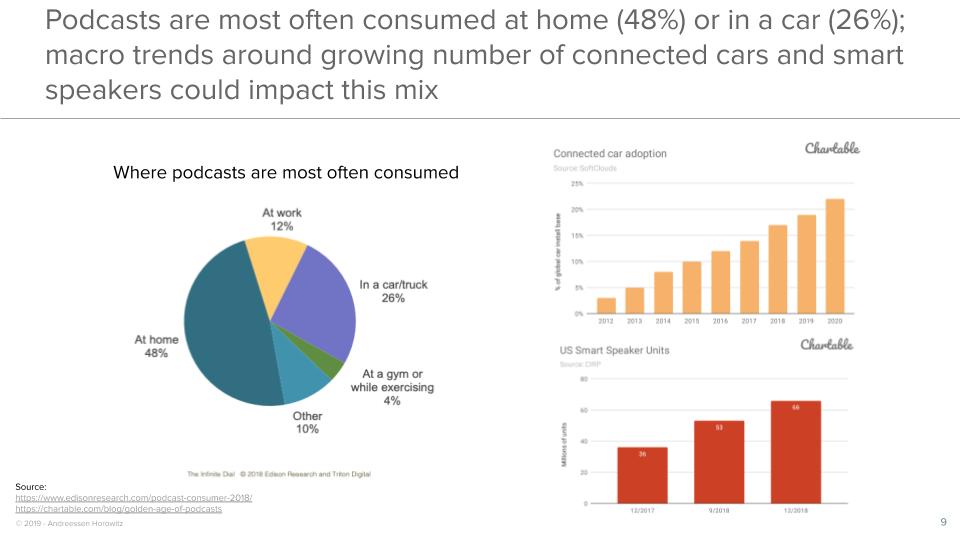

What may surprise people living in heavy commuter markets is that listening primarily happens at home, which represents almost half of all podcast consumption.

We would also anticipate that more recent technologies like Bluetooth-enabled cars and smart speakers — now owned by 53M Americans or 21% of the population — could change the mix of where podcast listening happens.

The lion’s share of podcast listening happens at home, followed by taking place in a vehicle.

A brief history of podcasting

Simply put, podcasts are digital audio files that users can download — or in some applications, stream — and listen to. While podcasts differ widely in terms of content, format, production value, style, and length, they’re all distributed through RSS, or Really Simple Syndication, a standardized web feed format that is used to publish content. For podcasts, the RSS feed contains all the metadata, artwork, and content of a show.

To listen to a podcast, a user adds the RSS feed to their podcast client (such as Apple Podcasts, Spotify, etc.), and the client then accesses this feed, checks for updates, and downloads any new files. Podcasts can be accessed from computers, mobile apps, or other media players. On the podcast creator side, creators host the RSS feed as well as the show’s content and media on a hosting provider, and submit the shows to various directories, such as Apple’s podcast directory.

Podcast content is typically available for free, though creators can choose to set up private RSS feeds that require payment to access.

Current headlines about podcasts today hail them as the next major content medium, describing them as “suddenly hot”, as the next battlefield for content, and as an “antidote” for our current news environment:

How did this “suddenly” happen? As with all tech trends, it had a longer and slower start before going more mainstream. Let’s time travel back 15 years ago, when there were no smartphones and the internet was accessed only through desktop computers.

In February 2004, journalist Ben Hammersley wrote about the emergent behavior of automatically downloading audio content in a February article in The Guardian:

“MP3 players, like Apple’s iPod, in many pockets, audio production software cheap or free, and weblogging an established part of the internet; all the ingredients are there for a new boom in amateur radio. But what to call it? Audioblogging? Podcasting? GuerillaMedia?”

In doing so, Hammersley accidentally invented the term we still use today, “podcasting” — a portmanteau of “iPod” and “broadcast” — for this kind of content. The word was added to the Oxford English Library later that year.

In 2005, podcasts were added to the iTunes store, with Steve Jobs saying, “Podcasting is the next generation of radio, and users can now subscribe to over 3,000 free Podcasts and have each new episode automatically delivered over the Internet to their computer and iPod.”

In 2007, the first iPhone was introduced, but it wouldn’t be until 2012 that Apple created the Podcasts app. The release of this app is widely considered an inflection point for the industry, as it put podcasts a single tap away for hundreds of millions of users around the world. Ironically, a few months later, Google discontinued its own podcast app called Google Listen.

In 2014, the first season of Serial aired, considered to be the first breakout podcast, with its narrative audio journalism drawing in 5M downloads in the first month.

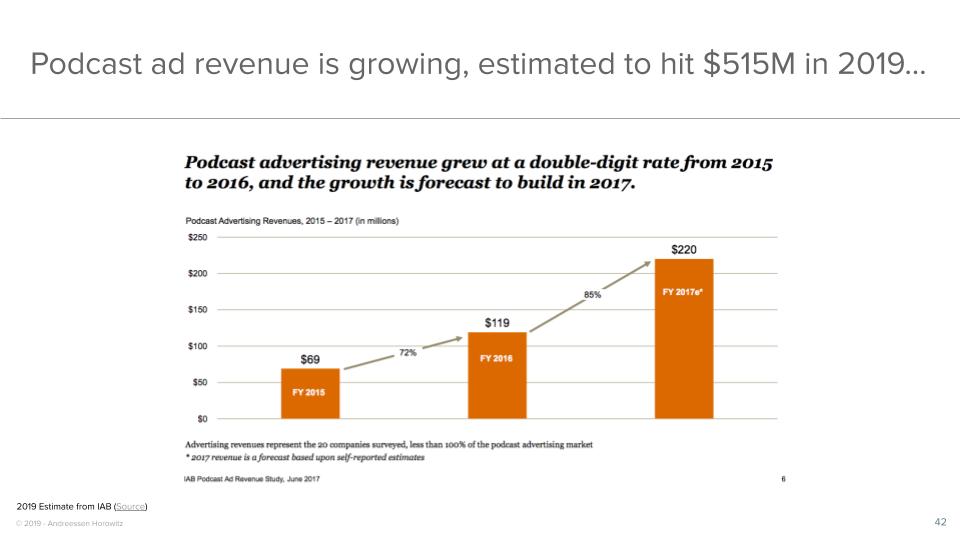

In the past 5 years, there’s been an explosion of listening behavior and innovative content. New devices made it easier to listen: Alexa launched in 2015, Google Home and AirPods in 2016. And an explosion of new content — ranging from daily news to narrative to talks shows — met the growing listener appetite. In tandem, ad spend has been growing steadily each year, from $69 to $220M in 2017 [source].

The app landscape

Many apps for listening to podcasts, but little differentiation or loyalty

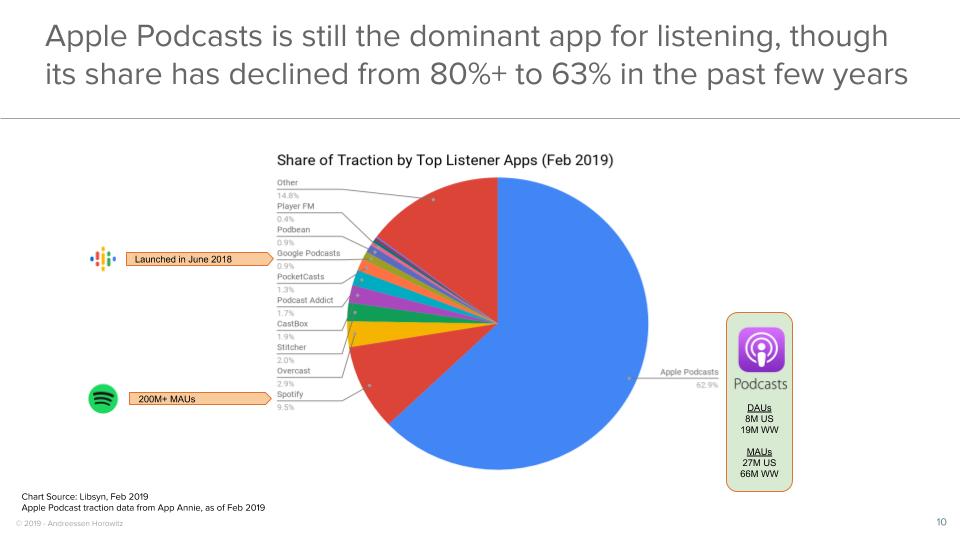

Apple Podcasts played a pivotal role in the development of the industry and remains the dominant app for listening. However, its market share has fallen in the last few years, from over 80% to 63%. The corollary to this stat is that historically, podcasting has been predominantly an iOS user behavior, given that Google didn’t have its own native application, something that changed last summer with the launch of Google Podcasts.

Apple’s share of the podcasting market has slipped from over 80% to 63%, while Spotify has quickly grown to almost 10% of the market.

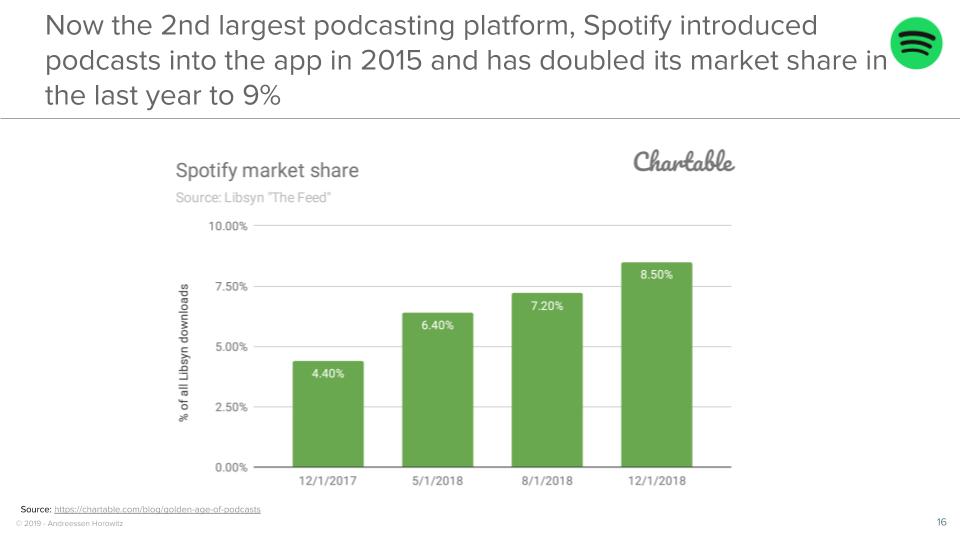

Spotify — which has made a big push into podcasts in just the past couple years — now accounts for almost 10% of listening.

Beyond these two large companies, there’s a long tail of listening apps from smaller companies. Most of these apps all have roughly the same content, given widely open directories of podcast RSS feeds. And there’s hundreds more listening apps out there. The barriers to entry for creating a new podcast app are quite low, since content is all distributed via RSS feeds and anyone can access them. There are also tools for creators to create their own podcast app from their own RSS feed.

A note on comparing listening apps: metrics between apps are not entirely an apples-to-apple comparison, as some apps (like Apple Podcasts, Overcast, and Stitcher) auto-download shows that users subscribe to, whereas others (e.g. Spotify, Castbox) don’t continuously download new episodes. This affects comparisons between apps and may overstate the traction of listening apps that auto-download shows. The industry has not standardized around what defines a download or listen.

A taxonomy of consumer podcast apps

From our research, users seldom feel passionately — either positively or negatively — about the podcast app they’re using. This suggests that the audio content itself is the core element users are engaging with, and since the content is the same on all apps, users don’t feel particular affinity to any one listening app.

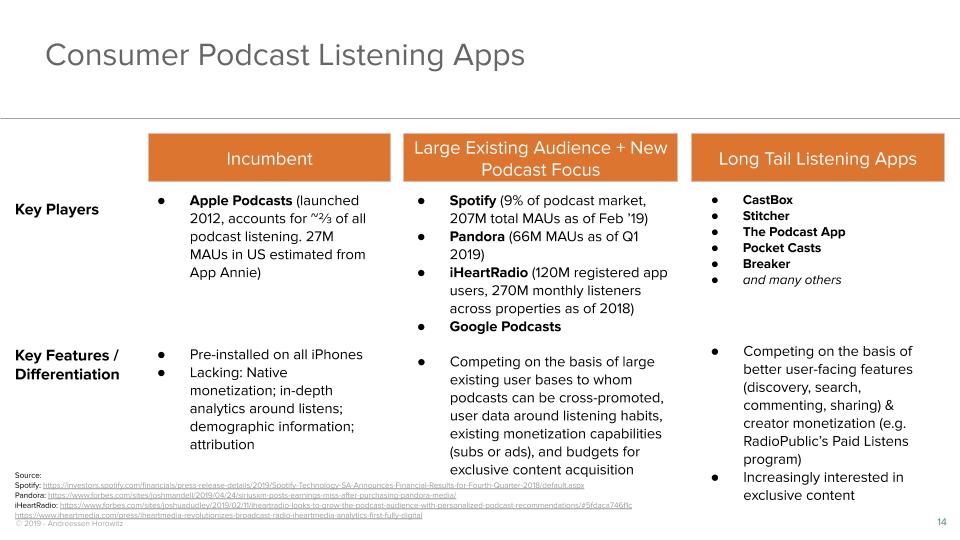

Three major categories of consumer podcast listening apps: the incumbent, large existing audience and new podcast focus, and long tail listening apps.

I categorized consumer podcast listening apps into three major categories:

- The incumbent: Apple Podcasts

- Companies with large, existing audiences who are newly focusing on podcasts

- Long-tail listening apps

The major feature of Apple Podcasts is that — despite its shortcomings in user-facing features and monetization — it’s pre-installed on all iPhones, making it a tap away for 900M people worldwide. We estimate that Apple Podcasts has 27M monthly active users in the U.S., based on App Annie, so a sizeable absolute number but relatively small compared to the total install base. Though Apple accounts for the majority of podcast listening, the company currently doesn’t monetize podcasting at all — all ads that you hear on podcasts are a result of advertisers and podcasters connecting off-platform.

For some users, the app is a basic, functional listening app, as compared to other media apps and products, with rudimentary categorization and discovery features. For some creators, the features it currently lacks include native monetization capabilities, in-depth analytics, demographic information for listeners, or any attribution for where listeners come from. Since Apple Podcasts launched in 2012, the app itself has changed very little. The New York Times wrote in 2016 that “the iTunes podcasting hub that Mr. Jobs introduced remains strikingly unchanged,” and beyond adding more analytics features in 2017, the same still holds true today.

In the second category, there’s a number of media and technology companies that have large existing audiences making a big push into podcasts, including Spotify, Pandora, and iHeartRadio. The strategies for these companies are mostly centered around leveraging their existing audiences to cross-promote podcasts; using listener data to personalize listening experiences or to help surface relevant podcasts; and leveraging their reach and existing monetization mechanisms to help creators earn more revenue. Google, which launched a standalone Podcasts app last year, has talked about making podcasts a first-class citizen in terms of surfacing podcast content in search results, as well as the growth opportunity that Google users worldwide represent in terms of potential podcast listeners.

Finally, there’s the long tail of podcast apps. These are comprised of startups and a fair number of non-VC funded companies. These apps are predominantly competing on the basis of better user-facing features such as improved discovery, search, and social capabilities, as well as creator monetization including their own ad networks or direct user monetization features. Increasingly, startups in this last category are also looking for other ways to distinguish themselves outside of listening experience — including experiments with exclusive, sometimes paid, content.

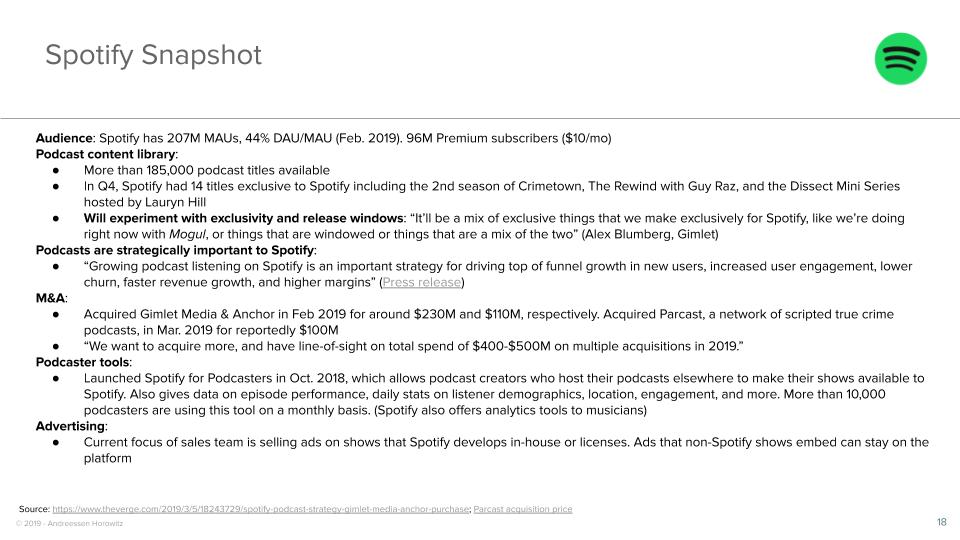

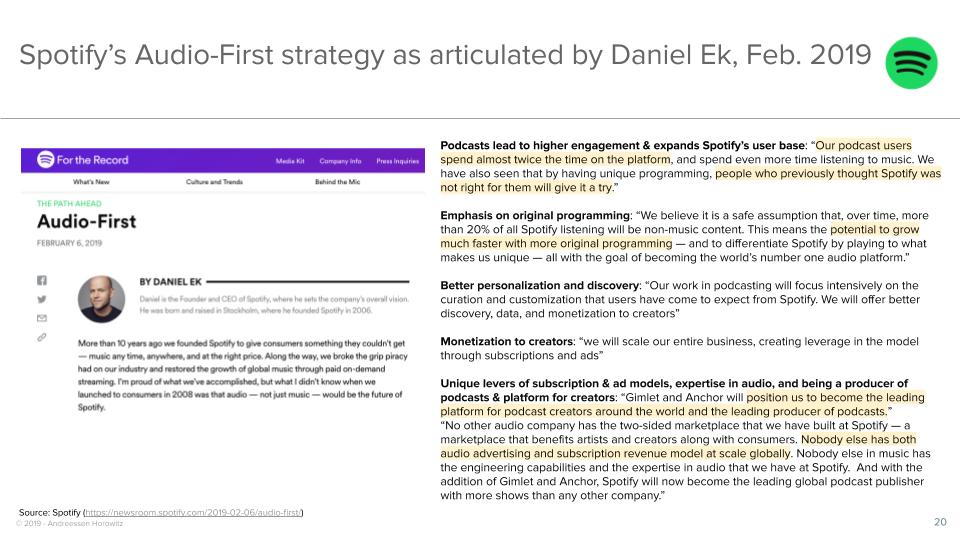

A discussion about shifting user behavior around consuming podcasts would be incomplete without calling out Spotify. In just the past few years, Spotify has burst onto the podcast landscape, moving from being music-centered to “audio-first”, and becoming the second largest platform for listening after Apple Podcasts.

Spotify’s market share in podcasting has grown to 9% in a few short years based on data from Libsyn, a podcast hosting provider, and the company has laid out plans to become a destination for all types of audio content.

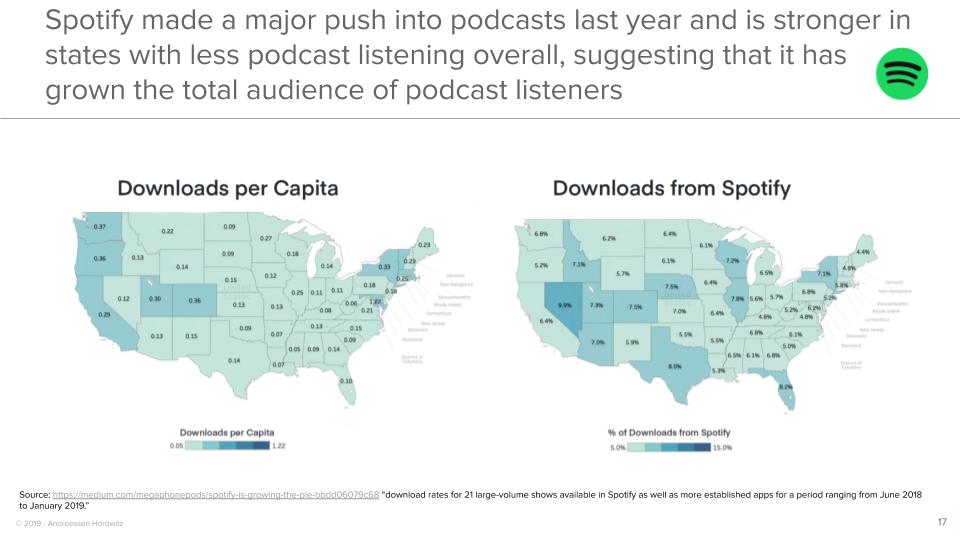

Interestingly, Spotify may be growing the market of podcast listeners: the data below from Megaphone (formerly Panoply Media) shows that downloads of podcasts from Spotify happen in geographies that historically had fewer podcast downloads.

Downloads data suggests that Spotify is growing the audience of podcasting.

Spotify also accounts for two of the largest podcast acquisitions in industry history — Gimlet and Anchor — which occurred earlier this year. The company has committed to spending hundreds of millions of dollars more on acquisitions, and has also stated that podcasts are strategically important for driving increased user engagement, lower churn, faster revenue growth, and higher margins than the core music business.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek’s letter about their “audio-first” strategy is worth a read. He predicts that over time, more than 20% of listening on Spotify will be non-music content, and that the Anchor and Gimlet acquisitions position Spotify to be a leading platform for creators, as well as the leading producer of podcasts.

Podcast creator and listener activity

Extreme power curve among podcast creators

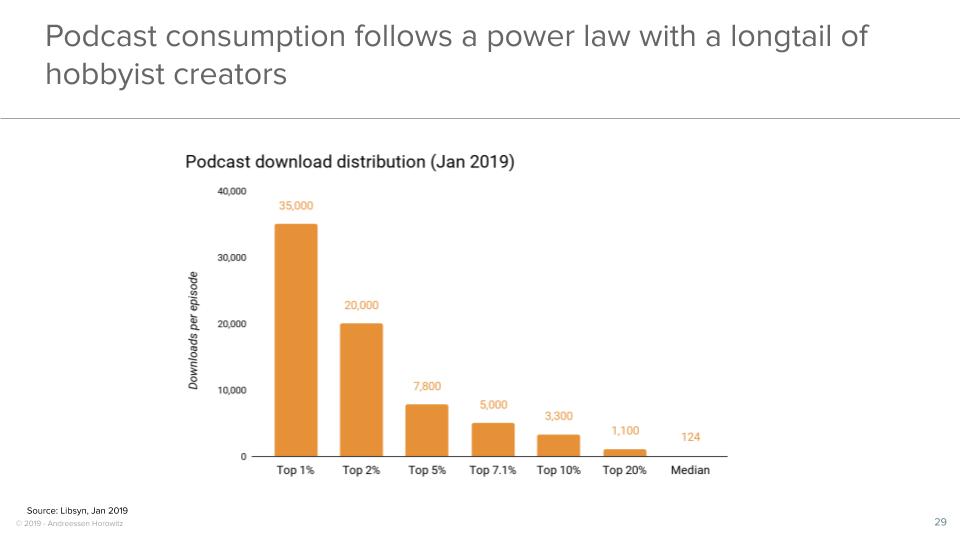

If traction among consumer listening apps appears highly concentrated among a small number of apps, the same can be said of podcast creators. The creator landscape reflects a power-law type curve, with most of the podcasts consumed in the top 1% of all content.

According to Libsyn, one of the oldest podcast hosting providers, the median podcast only has 124 downloads per episode — but the top 1% has 35K downloads per episode.

A taxonomy of podcast creators

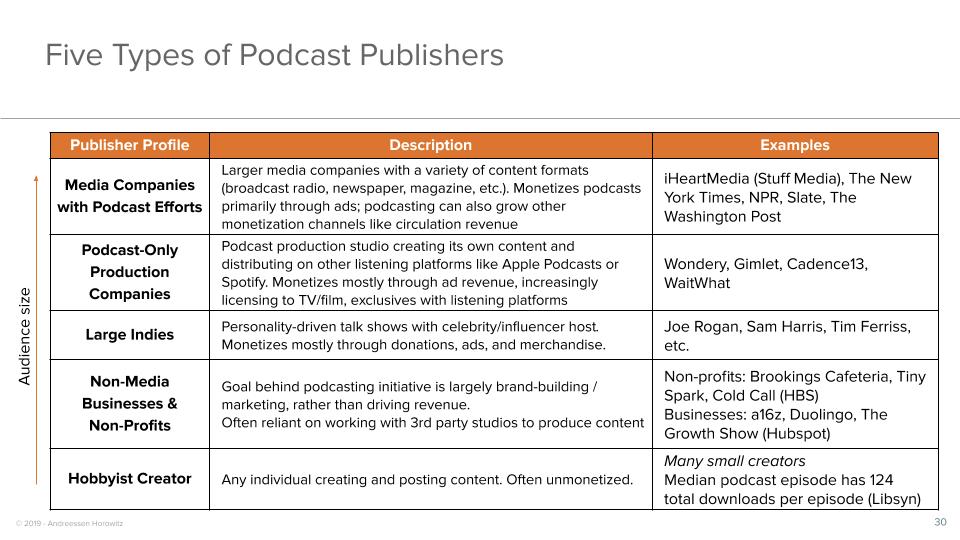

I created a taxonomy of the podcast creator ecosystem as a rough framework for thinking about the various types of creators, roughly split across five categories: media companies with internal podcast efforts; standalone podcast-only studios; large indies (including what our editor-in-chief Sonal Chokshi calls “cult-of-personality” shows); non-media businesses and nonprofits; and the long tail of hobbyist creators.

In order of descending audience sizes, these categories are:

- Media companies that have internal podcast departments, whose goals in podcasting can range from audience development to diversifying revenue. Examples of companies in this category include traditional media companies like the New York Times, where audio was treated as an experiment before The Daily became a major hit in 2017; radio platforms like iHeartRadio, which bought Stuff Media to double down on podcasting; and digital media companies like Barstool Sports, a sports and pop culture blog which produces a number of podcasts. These companies can leverage their existing user base to drive listenership for the podcast — and if the podcast becomes popular, vice versa.

- Podcast production companies focused mainly — if not exclusively — on podcasting, which necessitates building a viable business from podcasting alone. Their revenue primarily comes from advertising, which means those podcasts need to amass large, repeatedly engaged listener bases. Examples include Gimlet (the creator of Reply All, StartUp, Crimetown, and others), acquired by Spotify in early 2019; and Wondery (Over My Dead Body, Generation Why, Dr. Death).

- Large indies and personality-driven talk shows primarily hosted by one or two personalities. These podcasts monetize mostly through ads, donations, and sometimes merchandise or live events. Examples include Tim Ferriss, Sam Harris, Rachel Hollis, Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark (My Favorite Murder), Roman Mars (99% Invisible), Joe Rogan, and many others.

- Non-media businesses and nonprofits that also produce podcasts. The primary goal behind these podcasting initiatives is mostly brand-building and marketing, rather than driving revenue. Mailchimp and HBS podcasts fall into this category.

- Lastly, there are the individual hobbyists creating and posting content — often un-monetized and with very limited audiences. Podcasting tools like Anchor and others are democratizing the ability to launch a podcast, which will lead to more and more hobbyist creators.

Note that these categories serve as a rough segmentation of the creator landscape, because there is a lot of overlap and blurriness between some of them.

For instance, NPR — the #1 podcast publisher in terms of downloads — produces many hit podcasts including Hidden Brain, How I Built This, Planet Money, and others, and is considered by some as having raised the profile of the medium overall. NPR sells ads on its podcasts and has teams of designers, planners, and strategists, but is technically a non-profit media organization. While podcasting has deep roots in public radio — This American Life, for instance, launched in 1995 under WBEZ (Chicago Public Radio) — the non-profit aspect of these organizations has implications on the business. Alex Blumberg, the CEO of Gimlet and a cofounder and producer of Planet Money, was reportedly frustrated with NPR’s slow decision-making and strict rules around advertising, which led him to found Gimlet: “‘We should be making more; people want more… There should be the Planet Money of technology! Of cars!’”

Rich variety of content

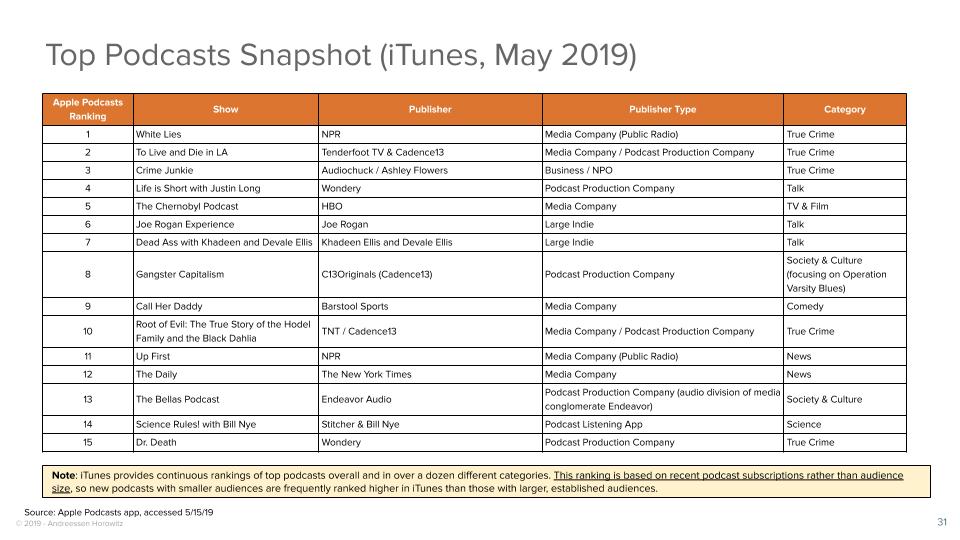

The top iTunes podcasts chart from May 2019 is interesting for its glimpse into the tastes of Americans who have iPhones. A small number of publishers account for multiple top shows, including Wondery and NPR. We can also see how much Americans love crime/mystery content, as well as talk shows!

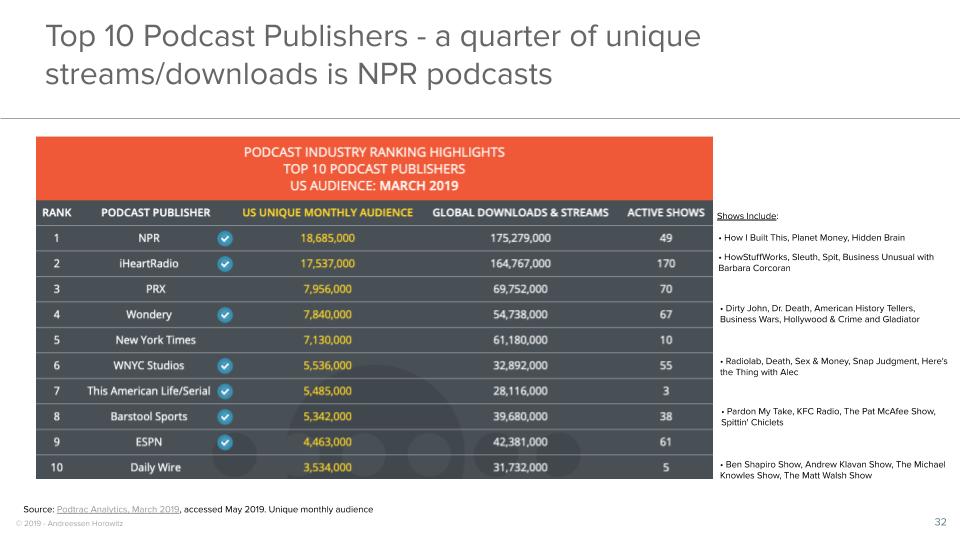

While NPR and iHeartRadio have roughly the same number of monthly downloads, NPR is able to accomplish this with just 48 shows vs. iHeartRadio’s 170. (Shows with blue check marks have gone through Podtrac’s podcast measurement verification process.)

Making money from podcasting

The current state of monetization in podcasting mirrors the early internet: revenue lags behind attention. Despite double-digit percent growth in podcast advertising over the last few years, podcasts are still in a very nascent, disjointed stage of monetization today.

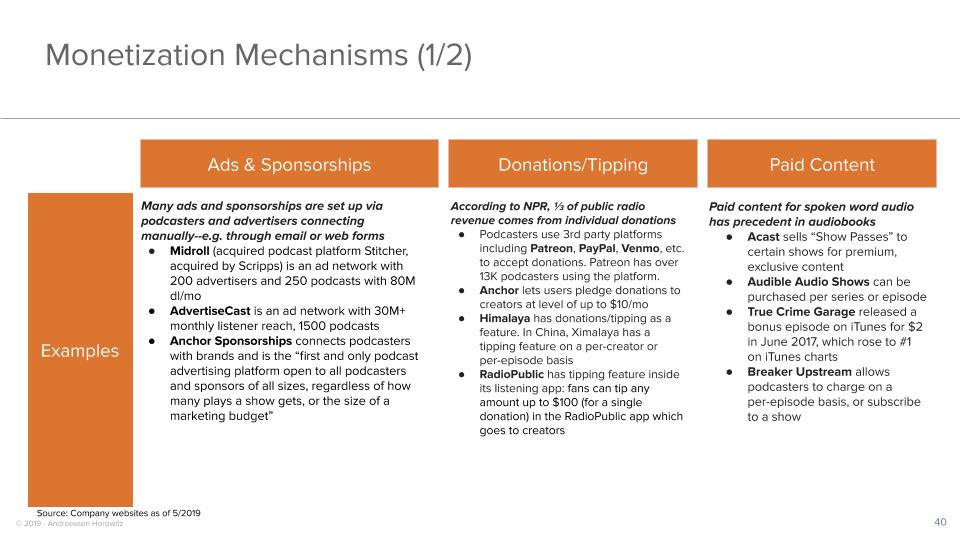

Today, podcasts primarily monetize via ads and listener donations. Though we’ve heard anecdotally from advertisers that podcast ads are effective — and are unique in their ability to reach a hard-to-access, attractive demographic — the ad buying experience is manual and tedious. Especially compared to purchasing other forms of digital advertising, since the dominant listening platform (Apple) doesn’t offer a way for hosts and brands to connect.

As a result, you’ll see price sheets floating around online for major shows, with set rates to sponsor episodes, based on historic downloads figures. Ad networks in the podcasting space like Midroll Media and AdvertiseCast aim to make this process easier, while more new listening platforms are also enabling easier advertising, for instance by selling ads on behalf of shows in its network.

But advertising doesn’t always cover the entire cost of producing a show, even for hit shows. Serial is one of the most successful podcasts ever — and the first ever podcast to reach 5 million downloads — and asked for donations in order to fund the production of the second season. This American Life also publishes requests for donations, including these blogposts detailing the high costs of producing the show, with Ira Glass writing, “People sometimes ask me if it’s frustrating, having to request donations directly from listeners. It’s not. It’s the fairest way to fund anything: the people who like these stories and want them to exist, we pitch in a few bucks.”

Donations to podcasters primarily happen off-platform today, via third-party tools such as Patreon, PayPal, and Venmo. The top podcaster on Patreon, Chapo Trap House, a political humor podcast, earns over $131K per month from almost 30K patrons (link). Himalaya, the U.S. podcasting app backed by the Chinese company Ximalaya, has a donations feature. And some other listening apps also have introduced one-off tipping capability or patronage features.

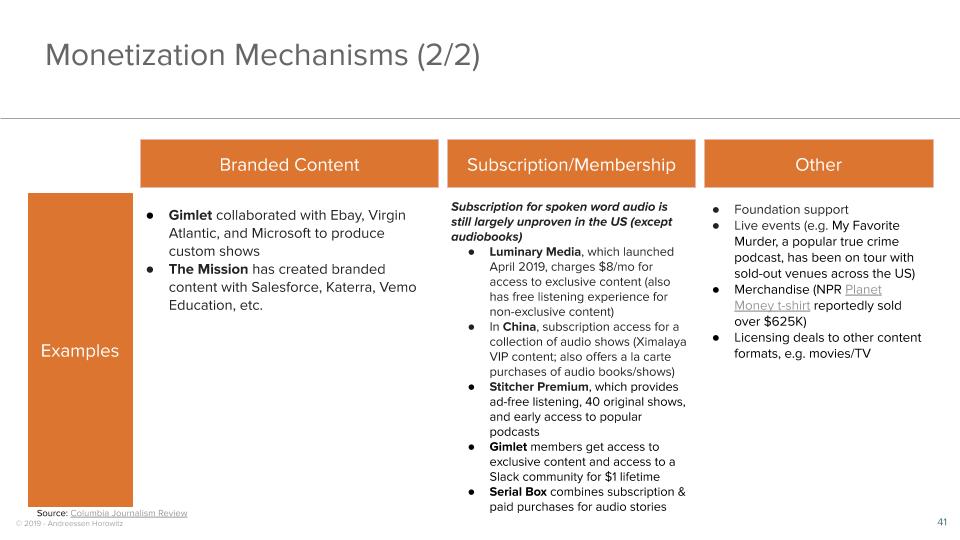

Another monetization mechanism that companies are experimenting with is branded content. As opposed to advertising — which first start with the content and then sell ads to monetize — branded shows create a podcast in collaboration with a company, for a fee. Examples include The Mission, which is selling to enterprises to create branded podcasts — for instance, a podcast called The Future of Cities, sponsored by Katerra; and Gimlet, which has collaborated on shows like The Venture with Virgin Atlantic. By removing dependence on ads for monetization, branded shows like these are able to go deeper into a subject matter and create more niche content that doesn’t rely on listening volume to generate revenue.

There’s also a lot of activity happening right now in the subscription and membership space. Recently-launched podcasting app Luminary Media (which bills itself as the “Netflix for podcasts”) charges $8 a month for access to a slate of more than 40 exclusive podcasts, and the app also has a free listening experience. The launch has been bumpy, with issues ranging from podcasters taking offense at their tweet that “Podcasters don’t need ads”; to controversy about removing links in show notes, including donation and affiliate links that help podcasters monetize; to using a proxy server to serve podcasts, which made it challenging for podcasters to receive accurate analytics. Luminary’s launch serves to signal a few things — that the golden age of investing in podcasting is underway in terms of dollars flowing in, but also that getting the buy-in of creators is just as important as winning over consumers in building a new platform.

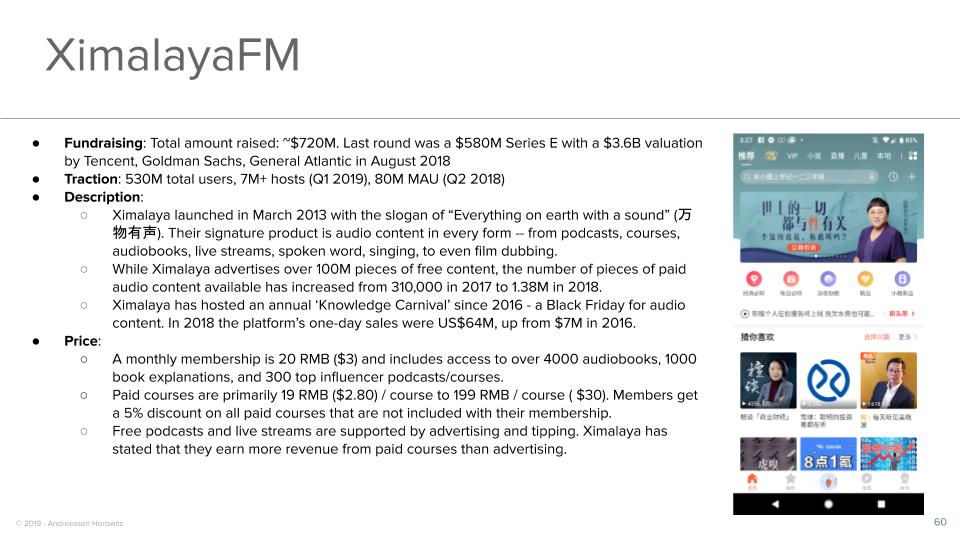

The model of subscription premium audio content is popular in China, where Ximalaya, a unicorn consumer audio platform, has a subscription feature for $3 monthly that enables users to access over 4000 e-books and over 300 premium audio courses or podcasts. Audio content is also available a la carte starting at $0.03 per short, serialized book chapter, or anywhere from $10 to $45 for paid audio courses.

Other monetization models we’ve seen include grants or foundation support, ticket sales for live events, and merchandise sales. There’s also licensing deals happening with the likes of HBO, Amazon, Fox, and other content companies who view podcasts as a source of intellectual property and want to adapt them into movies and TV shows. For instance, Gimlet’s scripted podcast Homecoming debuted as an Amazon Original Series in November 2018. The directionality of influence goes both ways: some podcasts are offshoots of other content — such as HBO’s Chernobyl podcast which discusses each episode of the mini-series — or written content — like Binge Mode’s deep dive into Harry Potter.

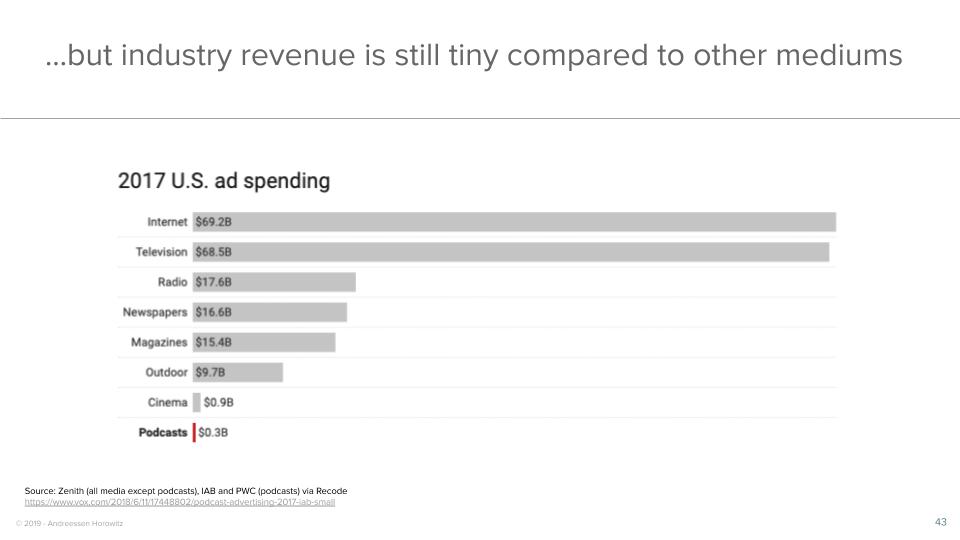

Podcast ad revenue is growing but is still tiny compared to other content formats

In 2019, the podcast industry ad revenue is estimated to hit over $500 million dollars, having doubled each year for the past few years. However, overall industry revenue is still tiny compared to that of other content mediums.

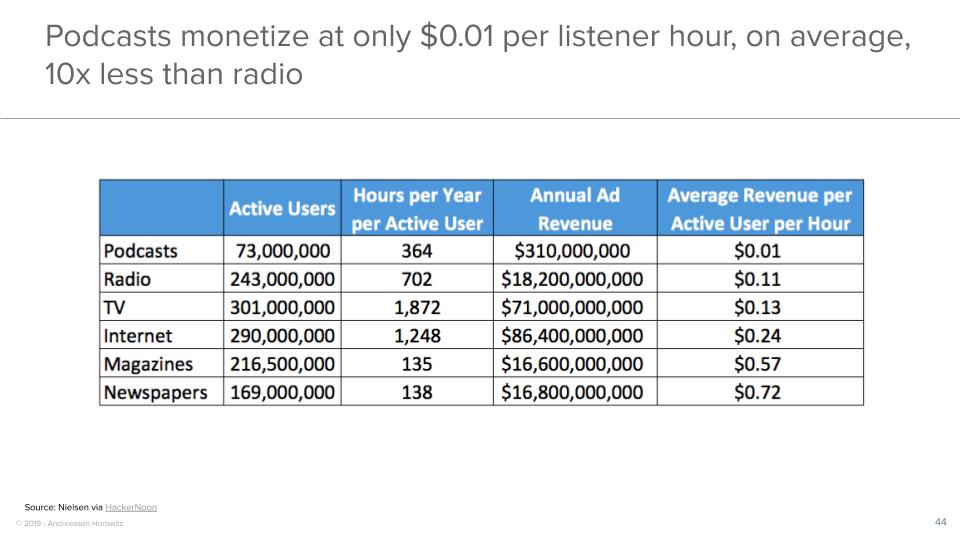

In particular, based on average revenue per active user per hour, podcasts monetize at a fraction of other content types.

Though podcast ad revenue is growing, the medium monetizes at a fraction of the rates of other content types (source: Nielsen via Hacker Noon)

Limitations of podcast advertising

Based on our conversations, lag in monetization isn’t due to lack of efficacy of ads. Various studies, including by Nielsen and Midroll Media, have found that podcast ads meaningfully increase purchase intent.

Why is podcasting monetization so low? Reasons include:

- Inability to monetize directly on the dominant platform, Apple Podcasts.

- The long tail of podcasters not being able to monetize because advertisers only want to work with podcasts that have a high level of listenership. Given the lack of advertising inside major listening apps, advertisers need to connect off-platform with podcasters — whether directly or through an ad network. This manual process means that for most advertisers, the long tail of podcasts requires too much time and effort to find and work with.

- Lack of clarity around actual listens. For a long time, downloads were used to proxy delivered ads, but a “download” doesn’t necessarily mean a “play”.

- Detailed listener data is also not available. There’s also a lack of sophisticated targeting tools on par with what Facebook and other digital platforms offer advertisers.

Today, podcast ads are primarily direct response, with ads read by hosts. You’re probably familiar with ads on podcasts with hosts talking about a product and verbally sharing a discount code. Podcast ad attribution is very rudimentary: the common methods of attribution are vanity URLs (for instance, http://www.ecommercewebsite.com/<podcastname>); promo codes entered at checkout; and surveys asking users, “How did you hear about us?”

Despite all these issues and barriers to monetization, podcasts are still able to command a premium CPM of $25 to $50, based on downloads, due to their efficacy. And the highest performing shows can cost even more.

How much are podcasters making?

While the majority of shows don’t monetize at all, the most successful ones can earn substantial revenue through advertising. A couple of data points: in July 2018, The New York Times’ The Daily podcast was projected to book in the low eight-figures revenue in 2018 from ads, and had 5 million listeners monthly and 1 million listeners daily, or about $2 to $10 revenue per monthly listener. For context, The Daily was only started in January 2017. For comparison, in 2018, Spotify earned $605M from 111M monthly ad-supported listeners, or $5.45 per free listener.

The New York Times as a whole had $709 million in digital revenue in 2018, so podcasting is still small relative to their entire business, but has an outsized impact on brand awareness. Michael Barbaro, the host of The Daily, shared in Vanity Fair that “When we started the show, we had many goals. We didn’t realize we were going to make money that was actually going to get pumped back into the company.”

Blogger and podcaster Tim Ferriss has written that if he wanted to fully monetize the show at his current rates, he could make between $2-$4 million per year depending on how many episodes and spots he offers.

Some back-of-the-envelope calculations around how much podcasters are making: Assuming CPMs of $25-50, if a podcast is in the top 1% in terms of downloads episode, or has 35,000 downloads per episode, each episode could generate about $4,000 per episode with two ad slots.

Audio trends and lessons from China

Over the past five years, dedicated audio apps in China have been growing quickly. In fact, online audio market users grew by over 22% in China in 2018, a faster rate than either mobile video or reading. Looking at China can illustrate potential business models — partly through adopting an audio-centric approach rather than adhering to a strict definition of podcasting.

Ximalaya FM, which last raised $580 million in August 2018 with a $3.6 billion valuation, is an audio platform with over 530 million total users and 80 million monthly active users. Ximalaya’s product is audio content in every form — from podcasts and audiobooks to courses, live audio streaming, singing, and even film dubbing. The monetization models are just as diverse: there’s advertising, subscriptions, a la carte purchases, and donations / tipping. Interestingly, not all paid content is included in their subscription membership (similar to Amazon Prime Video’s mix of free and paid content), but members get an additional 5% discount on any exclusive content.

China’s unicorn audio platform Ximalaya helps illustrates creativity in product and business models.

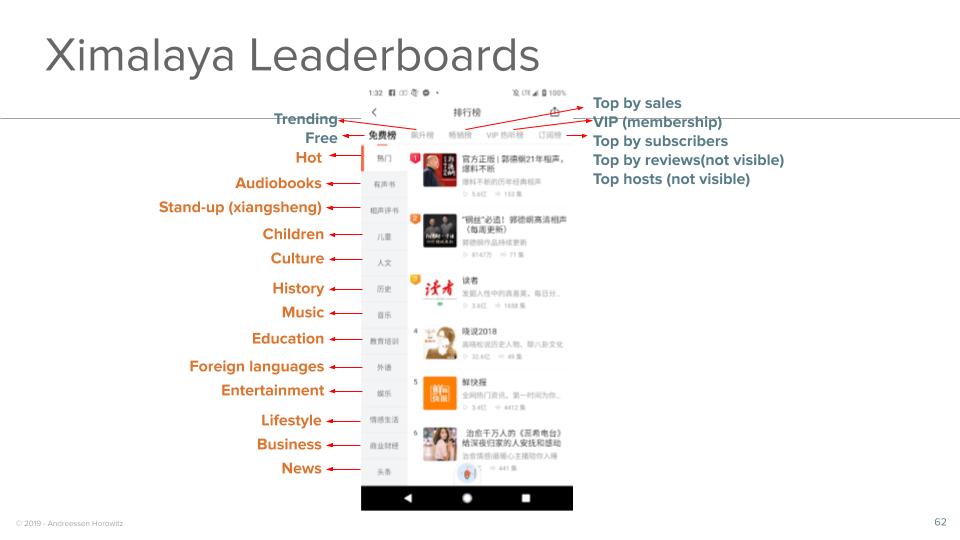

As a result of the platform’s diverse purchasing models, the discover leaderboard filters not only by content category, but also according to monetization method, top hosts, most subscribers, and what’s trending on that very day.

Ximalaya leaderboards can be sorted by top grossing content, top hosts, highest number of subscribers, and also by category of content.

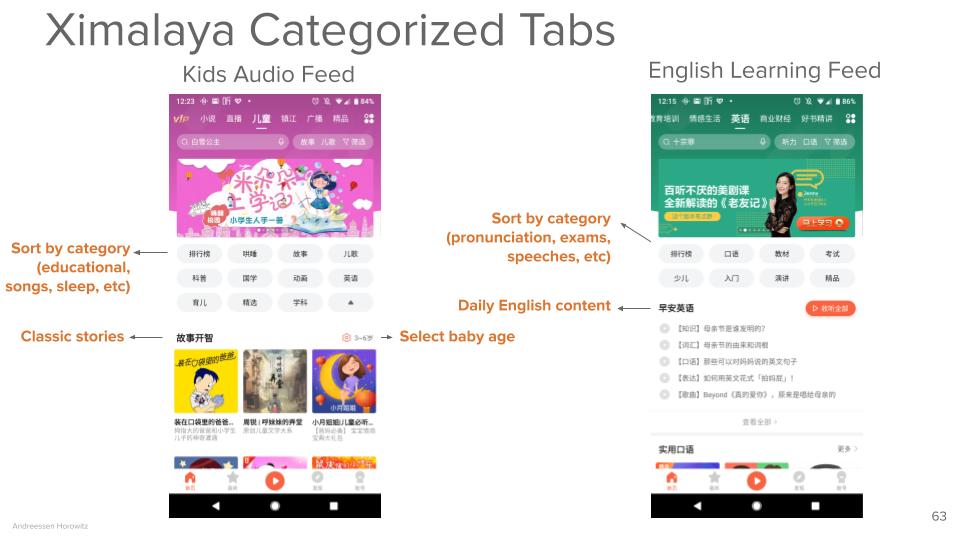

The app contains many different tabs with categorized content to allow users to optimize their listening experience. As the below screenshots indicate, users with children can get their feeds custom-curated for family-friendly listening; and users interested in learning English can get daily custom curated playlists with lessons, techniques, or even testing advice. In total, there are over 50 interest-based feeds available for users to choose from.

Ximalaya features customizable feeds of audio content.

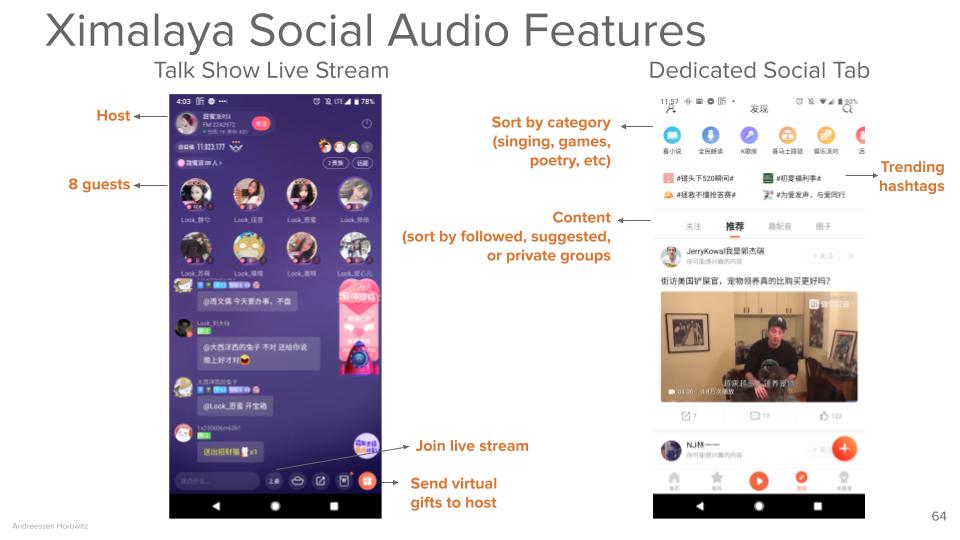

Ximalaya places a large emphasis on social interaction and community, which also has its own monetization model. One of the app’s most popular features is live audio broadcasting — which resembles live video, but through voice only — where users can host their own channel, invite other broadcasters, and earn money through virtual gifts from their listeners. Popular live streaming categories include music (singing songs or talking with music in the background); chatting about relationships; or discussing anime. Meanwhile, the Discover tab curates audio content into a custom social network so users can see not just the most popular content, but also what people are saying about it.

Ximalaya social features include live audio broadcasting — monetized via virtual gifting — and a social feed of other users’ activity.

Ximalaya illustrates a potential path for the development of audio platforms in the U.S., through its wide range of content types, monetization strategies, and interactivity. Examining the product may also hint at experiments it could run with Himalaya, its U.S. podcasting startup.

Beyond Ximalaya, social audio is a growing category in China, with apps like Hello (live audio broadcasting); KilaKila (an anime community with live audio and video broadcasting); and WeSing (a social karaoke app), all of which monetize through virtual gifts. Other apps such as Soul, Zhiya, and Bixin leverage audio for making friends, dating, and even video game companionship. These apps showcase the potential of audio to serve as a platform for social interactivity — voices act as a core component of users’ identity and are the medium through which individuals interact.

Startup trends, challenges, and opportunities

Biggest outcomes: no large standalone companies yet

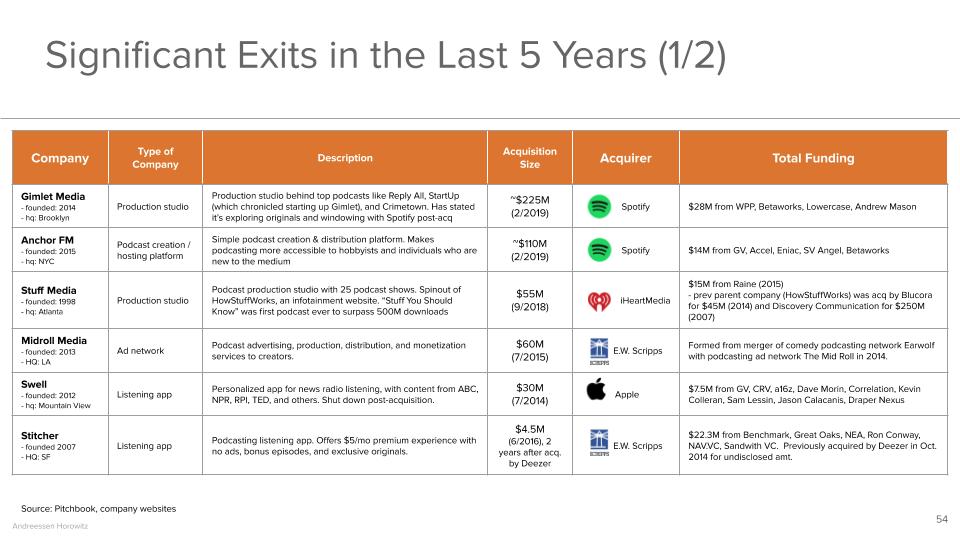

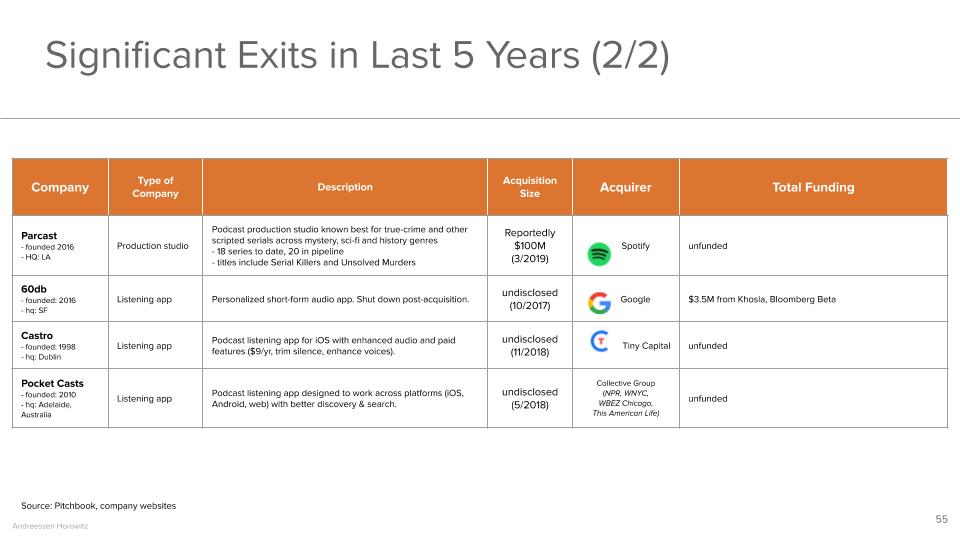

Early 2019 saw the two largest ever exits in the podcasting industry — but against the larger backdrop of venture-backed companies, the exits were still small. The industry hasn’t yet seen a “Facebook buys Instagram” moment — or a large independent company emerge.

Most acquisitions have been for listening apps or podcast production studios. Early 2019 saw the two largest exits ever for the podcasting industry, which were both to Spotify.

In early 2019, Spotify acquired Gimlet Media, the studio behind top podcasts including Startup, Crime Town, and Reply All, for over $200 million; and Anchor FM, a podcast creation and distribution platform that aims to make podcasting extremely simple and enable anyone to start a podcast using only their smartphone, for about $100M.

Beyond these two companies, there have been a number of smaller acquisitions in the space. Most of these exits have been “acquihires” of small listening apps that were subsequently shut down post-acquisition. More recently, podcast studios with expertise producing popular content have also been a target of acquisition, including Stuff Media (to iHeartRadio) and Parcast (to Spotify).

Startup trends: new apps, monetization experiments, production experiments

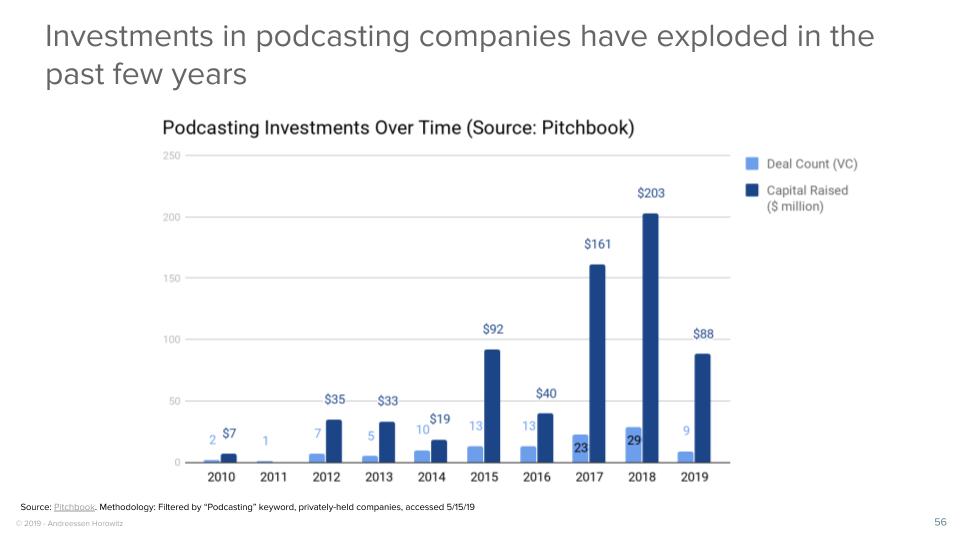

There’s been a flurry of funding activity in podcasting — so much so that some publications are wondering if we are in a “podcast bubble” (see for example this, this, and this). Here are some of the major trends we’ve seen.

2018 saw a record number of venture capital investments and capital raised for podcasting startups.

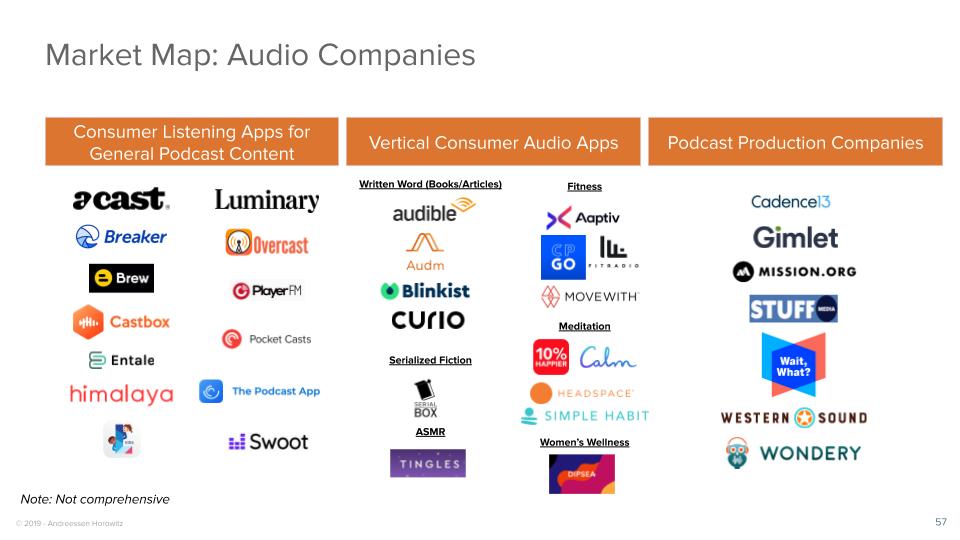

Startups are building new listening apps, verticalized audio platforms, and producing podcast content.

1. Consumer listening apps for general podcast content

A lot of startup activity is happening on the consumer side of listening apps: Many startups are capitalizing on the opportunity to create a better listener experience, given that Apple Podcasts is relatively simple and bare-bones, and until recently, there has been no default listening app for Android users. Issues these apps are addressing include better discovery of podcasts through algorithms, curation, or social signals; more effective ways to search for relevant content (e.g. by automatically transcribing podcasts so as to be able to search within them); or improved social features.

We on the consumer team tend to believe that better podcast discovery, recommendations, and other user-facing features alone aren’t sufficient to draw a large listener base. The core of what users are interacting with on a listening app is the content itself — after all, it’s normal for listeners to start playing audio content, then to background the app or put their phones away, so the listening app becomes secondary to the content. As a result, many podcasting startups have expressed interest in offering some flavor of exclusive content, as well as monetization options for creators, in order to further differentiate themselves.

Here’s a small sample of the approaches some of these new listening apps are taking:

- Charging consumers directly for podcasts — these apps’ exclusive podcasts account for a relatively small share of all of the content available in these apps. Examples include Luminary and Brew, both of which have subscription models for access to exclusive content, in addition to allowing users to listen to widely available free podcasts.

- Adding a social layer onto podcasts — to help with discovery and/or to capture the conversation happening around podcasts. Some early companies in this space include Breaker, Swoot, and others.

- Offering translation and transcription — essentially enabling episode-level rather than show-level discovery. Castbox, for instance, offers podcasts in multiple languages, as well as the ability to search within podcasts by transcribing content. The app also recently launched live audio broadcasting that allows anchors to interact with listeners via voice, text, and call-in and to earn tips from followers.

- Adding context — Since podcasts expose listeners to so much new information and prompt questions, these could be more seamlessly explored without disrupting the listening experience. Entale, for example, is a “visual podcast app” that uses AI to showcase relevant information to users as the podcast is playing — this could be displaying the Amazon link to a book that someone mentions, or linking to the Wikipedia page about a speaker’s biography.

- Specializing by vertical — For parents growing increasingly cognizant of exposing kids to screen time, having a curated selection of audio content targeted towards kids, suitable for entertainment and learning, can be valuable. Leela Kids, for example, is a children’s podcast app that curates kids-safe content.

2. Vertical consumer audio apps

Beyond general and for-kids podcasts, there’s also a number of adjacent audio apps with more focused content, including those targeting education, audio books, fiction, health and wellness and fitness. By focusing on a specific subject matter and going very deep, these apps aim to create full-stack listening experiences that combine original content around that particular vertical; user monetization mechanisms; and other value-added features that enhance the user experience and help users achieve their goals.

To give a few examples, Calm and Headspace are both guided audio meditation apps, which offer both free and subscription-only content that’s exclusive to their own platforms. Both have features beyond just the content itself that help users with mindfulness — for instance, daily reminders, streaks, visualizations and videos, etc. In the ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) vertical, Tingles is an app where fans can watch or listen to videos of ASMR content, filter by specific categories, and support creators through subscriptions. In the fitness category, Aaptiv, ClassPass Go, and MoveWith are examples of companies offering audio fitness classes across a variety of exercise types.

3. Podcast production companies

Lastly, there’s a surge of venture-backed podcast production companies creating podcast content and distributing it through third-party listening platforms. Examples of these include Wondery, the studio behind a number of hit shows including Dirty John, Dr. Death, and American History Tellers; and WaitWhat, the content incubator that developed Masters of Scale with Reid Hoffman and Should This Exist.

Most podcast producers are creating entertainment-focused, general interest content that appeals to a wide audience, likely because of their monetization model, which is primarily ad-supported. Since these content studios distribute through other platforms and don’t have direct relationships with end users, they need to monetize through advertising, which necessitates content that appeals to a wide audience and promotes lengthier consumption times and ongoing listening.

Successful production studios could be prime acquisition targets for media companies as efficient sources of IP, or for consumer listening apps as a way to differentiate based on content — and a number of startups in this space have already been acquired. Another possibility is that once these content companies generate enough listener traction, they could create distribution platforms of their own, and use these as a way to deepen listener relationships and diversify revenue, for instance by charging users for, say, early access to content, back catalogs, exclusive content, or other features.

So what are we interested in investing in?

Given the challenges with monetization, how can startups create a path to becoming a sustainable business? With the distribution and capital advantages that incumbents have — coupled with the fact that Apple and Google own the end mobile platforms, where are the opportunities for startups? And how do we evaluate these opportunities?

To understand startup opportunities, it’s important to consider where the incumbents and large audio companies like Spotify, Pandora, and iHeartRadio are uniquely advantaged:

- Consumer traction and awareness, and a large audience to which podcasts can be cross-promoted

- Large budgets for content production and acquisition

- User data on preferences and existing media consumption

- Existing monetization mechanisms, such as through ads, subscription

So how to navigate creating a large opportunity, given the above advantages?

We think the most promising players will combine the following aspects:

- Focus on audio content broadly, rather than exclusively podcasts. Just as the lines between blogs, articles, and other written content online have blurred, the same is happening with all audio content, and so we are interested in all types of content delivered via listening. As outlined above, podcasting was historically synonymous with audio distributed via RSS — now, with the rise of exclusive, paid podcasts, the distinction between podcasting and other audio content is becoming less meaningful.

- The potential for network effects. We’ve written extensively about network effects and how to measure them; the consumer team loves businesses with network effects! Network effects in audio could take different forms. Like many content platforms, there’s a two-sided marketplace network effect, where more high-quality content makes the platform more valuable to consumers, and more users makes it more appealing for content producers to distribute their content there. All things being equal, most users would prefer to use the platform that has the largest, best inventory of audio content. A social audio app could also have direct network effects, where the experience becomes better with more users/friends.

- While we prefer full-stack startups that own the experience end to end (positive feedback loops from listening app to content to monetization), we wouldn’t rule out breakout apps that are strong on any one aspect.

- High-quality differentiated and deeper content vs. broad, free libraries of shallower content. Since the large incumbents seek content that appeals to their large user bases, they’re less focused on seemingly niche, in-depth content. We also believe that for certain high-value content verticals, there’s potential to shift the burden of payment to businesses, schools, or other organizations — rather than on to end consumers.

- Consumption experience that enhances the experience of the audio content. This could be through live, social audio, or other features that increase stickiness and engagement. For instance, Headspace’s meditation streaks, animations, multi-level categorization, and session length options differentiate and enhance the experience, compared to listening to meditation audio content on general podcast listening apps.

- Alternative monetization beyond solely ads (Connie Chan has written a lot about this). Given the dominance of existing large platforms like Google and Facebook for ad targeting, it’s becoming increasingly challenging to build a new large company based on advertising alone. We are bullish about audio companies that are aiming to monetize users directly — this could be accomplished through charging for content that has higher perceived ROI, or by introducing payments as a way to alter the content experience (e.g. social recognition after tipping in live streams). More importantly, it’s also a way to align incentives of consumers with content creators.

What could some examples of these startups look like?

1. Vertical audio platforms

We’re excited about startups that are going deep within a particular vertical and building a full-stack audio experience tailored to that vertical. There’s less chance of incumbents competing directly here, given the more niche focus and fundamental differences in feature sets needed to enhance the user experience. We also see greater willingness for users to pay for content that has higher perceived ROI — for instance, various fitness and meditation/wellness audio apps have already gained high levels of traction in usage and monetization.

2. Interactive, social audio… finally

While people have been talking about it for years, we think there’s still an opportunity to finally have truly interactive, social audio. Without being too prescriptive on what this looks like (we want founders to tell us!), the fact is, audio content today is still largely broadcast in nature, with a one-directional flow of information from creator to listener. While there are some conversations happening around audio content (including on Twitter, Reddit, and other forums), they happen in a fragmented, isolated way, and on platforms that aren’t designed for that purpose.

Call-ins to radio and live talk shows are two current forms of interactive audio, with the social element fundamentally contributing to the content itself. Twitch also has podcasters who use the platform to live stream themselves while recording, sometimes responding to user comments which become part of the show’s content. There’s a number of startups enabling users to comment on static podcast content, but the social experience needs to become even more interactive to attract a wider audience and pull users off existing platforms. In China, live audio broadcast, group karaoke, and even audio dating products are flourishing, and there may be an opportunity to create an audio product that is more interactive and social for U.S. audiences, too.

3. Platforms that helps creators own their end users and monetize content

Most creators are disintermediated from their end listeners, since they produce content that is distributed solely through various third-party platforms. Given the brand equity and large followings that some creators have established, we believe that there’s an opportunity to give these creators a way to distribute their own content, own their customers, and to monetize through alternative sources besides advertising and off-platform donations.

Some influential podcast publishers have developed their own solutions to engage and/or monetize their own audiences, including Slate Plus, a paid membership program from Slate with podcast benefits including ad-free and bonus podcast; The Athletic, which launched over 20 exclusive shows behind a paywall in April; and BBC Sounds, an app that puts music, podcasts, and radio from BBC into one personalized destination.

But for creators who don’t have the technical or financial resources to develop their own apps or piece together various third-party solutions to accept payments or manage members, there could be a turnkey platform for creators. Down the line, there’s opportunity to create a network of these creators and listeners, along the lines of “come for the tool, stay for the network.”

The future

“If you think of audio as the way you think of, say, film, like we’re still in the black-and-white period of podcasting. What’s color going to look like? What’s 3-D going to look like?”

I love this quote from the host of Today, Explained, Sean Rameswaram — since we are still indeed in the black-and-white phase of podcasting.

Taking a step back, it’s amazing how much progress the industry has made since the Apple Podcasts app was introduced 7 years. It’s still early days, so if you’re building something that is related to any of these aspects, please drop me a line!

PS. Get new updates/analysis on tech and startupsI write a high-quality, weekly newsletter covering what's happening in Silicon Valley, focused on startups, marketing, and mobile.

Views expressed in “content” (including posts, podcasts, videos) linked on this website or posted in social media and other platforms (collectively, “content distribution outlets”) are my own and are not the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. AH Capital Management is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply any special skill or training. The posts are not directed to any investors or potential investors, and do not constitute an offer to sell -- or a solicitation of an offer to buy -- any securities, and may not be used or relied upon in evaluating the merits of any investment.

The content should not be construed as or relied upon in any manner as investment, legal, tax, or other advice. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Any charts provided here are for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, I have not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. The content speaks only as of the date indicated.

Under no circumstances should any posts or other information provided on this website -- or on associated content distribution outlets -- be construed as an offer soliciting the purchase or sale of any security or interest in any pooled investment vehicle sponsored, discussed, or mentioned by a16z personnel. Nor should it be construed as an offer to provide investment advisory services; an offer to invest in an a16z-managed pooled investment vehicle will be made separately and only by means of the confidential offering documents of the specific pooled investment vehicles -- which should be read in their entirety, and only to those who, among other requirements, meet certain qualifications under federal securities laws. Such investors, defined as accredited investors and qualified purchasers, are generally deemed capable of evaluating the merits and risks of prospective investments and financial matters. There can be no assurances that a16z’s investment objectives will be achieved or investment strategies will be successful. Any investment in a vehicle managed by a16z involves a high degree of risk including the risk that the entire amount invested is lost. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by a16z is available at https://a16z.com/investments/. Excluded from this list are investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets. Past results of Andreessen Horowitz’s investments, pooled investment vehicles, or investment strategies are not necessarily indicative of future results. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.