Author Archive

How to meet lots of people through LinkedIn

I’m winding down my last month in Seattle – sorry for the light blogging lately!

I’ve been very busy in the last week (and in the next 2 weeks) closing up shop in Seattle and meeting folks related to gaming and startups. One interesting question that pops up is, if you pick industry X, how do you meet lots of people who work in X. (In my case, it’s gaming)

Over the years, I’ve experimented with lots of different methods, but this time I tried a couple:

1) Subscribing to mailing lists and posting “Will you talk to me?”

Sometimes this works, but most of the time, you only get 2 or 3 people writing you back. I think the reason is that it seems random, people assume other people will help, and it’s generally a pain in the ass. I usually meet a couple through this method (in my case, spamming the IGDA mailing list) but this didn’t work well.

2) E-mailing friends and contacts at gaming companies

I also just e-mailed a bunch of friends and asked them to introduce me to people involved in gaming. This definitely worked, and I had at least 5 referrals this way, whom I’ve met for coffee. I think this completely depends on how “adjacent” the industry is – for example, if I’m in tech and I want to meet folks in video games, that’s not too bad. But if I wanted to meet people in the coffee or restaurant industry, that might be a lot harder since the connections are fewer.

3) Searching through LinkedIn and googling

It turns out, however, that the fastest way to meet a bunch of people is to use a combination of LinkedIn and Google. You use LinkedIn to see peoples’ names and companies – but you have no contact information. But then you follow up with Google and you can often find their e-mail address, or e-mail addresses for other folks within the same company (John.Doe@somecompany.com lets you guess their e-mail address) and finally, you can always e-mail the company address and specify the full name of the person you’re trying to reach.

This method has produced the most meetings out of any – you can easily use LinkedIn to find dozens of names, send brief e-mails with topics and ask to chat, and find at least a dozen folks willing to talk to you.

Definitely an interesting recent experiment, and I’m well on my way to understanding the gaming industry better. I’ll write up a post on what I’ve learned sometime later. Needless to say, the games industry is undergoing the same big revolutions as music, movies, and other digital goods.

The power of the mainstream publisher is both a stifling force on innovation, yet their power is diminishing over time. New models are emerging which focus on the idea of consumer choice, and having infinite choice, rather than traditional models which focus on finite shelf space (or screen space).

It definitely links to Chris Anderson’s idea of the Economics of Abundance rather than the Economics of Scarcity.

Here’s another great presentation on the topic from Raph Koster.

What a button can teach you

How cool is this site?? History of the Button.

Yes, that’s right, it’s an entire blog about buttons (like the kind you press, not the kind you have on your shirt). And I think it’s an incredibly fascinating angle on how people view technology. In an age where techie folks (like me) have our heads above the clouds thinking about complex technologies (usually with complex interfaces), it’s interesting to see how much richness (and difficulty) a button can give you.

Anyway, it reminds of this meme, which Steve Jobs keyed on the Apple Remote having 6 buttons and their competitors having dozens.

I suppose the software version of this is the perpetually ill-used dialog box. Lots of examples here. Here’s another set of examples.

(I see crap like this all the time, sadly)

Cute little blog

How to draw in MS Paint

People to meet in Seattle before I take off?

Today was a big day for me! It was my last day at Revenue Science, where I’ve been immersed in online advertising for the last 4 years.

I only have about 30 days before I move down to Silicon Valley and start at MDV.

Do you know anyone in Seattle that I should meet before I start my adventure?

If so, send me a note at voodoo [at] gmail [dot] com.

Yahoo’s problems with search monetization

Good article today for search nerds: Yahoo just needs to fix one thing: Monetization.

At the end of the day, the article is saying something pretty obvious: Yahoo needs to make more money based on the traffic they have :)

CPA is not the cure-all…

The question is, how? The author claims that somehow CPA is a solution – it may help, but at the end of the day, it’s a complicated issue. Sophisticated buyers (which constitute most of the dollar volume on these marketplaces) are already pricing based on CPA, even if they are bidding on price-per-click. They take the PPC they are bidding, the conversion rate on their landing pages, and figure out the effective CPA. So if you were to switch to CPA, they might love you more, but they won’t necessarily increase their pricing.

Also, CPC is a great compromise between publisher and advertiser – it’s part of the reason why it’s a very balanced pricing model. For publishers, they prefer CPM (guaranteed revenue) without being accountable for anything, particularly conversions. For advertisers, they prefer CPA since it’s guaranteed margin for them. CPC means that both party take risks.

Even so, CPA has been around for a long time. Commission Junction, Linkshare, and all those guys have been doing the CPA affiliate model for years. Recently, new folks have emerged like Adteractive and Azoogle who arbitrage high-ticket CPA offers against all sorts of different media. See Jay Weintraub’s awesome blog for a ridiculous amount of detail on this topic.

If not CPA, then what? (I don’t know)

I won’t dare to speculate how Yahoo should improve their monetization. I know there are people much smarter than me thinking about that exact topic. My only point is that it’s not as simple as pointing to something like CPA and claiming that’s the way out.

Fundamental economic issues?

The more worrisome issue is that it may be that Google has hit some weird critical mass with advertisers and publishers that will be very hard to compete with, in the long term. When an ad network first starts out, they have a chicken-and-egg problem since they need advertisers to attract publishers, and publishers to attract advertisers. There are ways to bootstrap, but it’s a difficult proposition.

But even when an ad network gets bigger, that chicken-and-egg problem doesn’t go away. The more advertisers you have bidding, the more competitive the pricing is, per click. This means that publishers (and Yahoo) can monetize their inventory better, but it’s hard to attract more and more advertisers without growing the amount of high performance inventory.

I believe people in 1999 called this a “network effect.”

Ultimately, Google may be too far ahead. I’ve heard rumors that Google is actually paying certain publisher partners over 100% revenue share(!), just because the economics dictate that the overall keyword market benefits even if they lose money at the deal. Basically these publisher partners keep the keyword prices very high, which pays dividends throughout the marketplace. This would point to the idea that Google is being so aggressive in defending their marketplace in a very savvy way, as to not give any chance for Yahoo and MSN to breathe.

So all in all, it may not be so easy to catch up with Google as to invest in technology. eBay is a very simple concept, yet its marketplace is VERY defensible. Just look at Yahoo Japan, which got a marketplace going first before eBay, and they’ve been able to keep their lead.

One last note on this – Microsoft sorta has a trump card in all of this since theoretically, they can create a bunch of high-value search out of thin air through Vista, and that’s an option no one else has. It may be possible that with that influx of inventory, they could grow without directly engaging Yahoo and Google in the Internet attention wars.

Fun casual strategy game :)

Link: DICEWARS – flash game.

Play it a couple times and you’ll notice there’s actually a bit of depth in there.

Here’s some analysis from one of my favorite bloggers, Danc from Lost Garden: Fighting the Dice Wars demon.

Why BitTorrent Inc. is no sure bet!

I’m going write about something near and dear to my heart: BitTorrent.

Many of you guys may have been reading about the company, recently, since they are rumored to be raising a huge venture capital round: BitTorrent Raises $25 million, Bram Cohen is History.

So first off, the technology and the adoption of the protocol are amazing. Just read the Wikipedia page for the staggering numbers. 55% of upstream traffic, 35% of all traffic on the Internet, etc. It’s all heady stuff. I’ve also chatted with Bram Cohen a couple times, and had dinner with him when he lived in Seattle, and he’s a smart guy and I wish him the best of luck. But since the positive rah-rah side of the equation is covered, let me explain some of the hurdles I see for the company, based on first-hand experience.

A quick history

My friends and I love BitTorrent. In fact, we loved it so much that as a side project in late 2004, Will Portnoy and I wrote a BitTorrent search engine called TowerSeek. We did a little research paper about it and released it to the world, under the name Monkey Methods Research Group. It was on Slashdot at some point, along with MIT Tech Review, G4 TV, a couple hundred blogs, etc., which totally crashed our servers – that was fun :) We thought that BitTorrent had already proven its value as a product, and ultimately, we could try to “bring it mainsteam” by building a search engine (which aggregated all the fragmented content), as well as creating a BitTorrent client in an Internet Explorer toolbar. That way, you could use this toolbar to search, download, and open files.

We learned a lot from this experience, which I’ll share below. Ultimately, we decided to focus on the creation of long-tail content, rather than facilitating mainstream stuff, which we saw as a difficult business model.

So after that, we started a media marketplace where people could go and publish stuff using BitTorrent. It was definitely an interesting experience, because after a couple months of tinkering and talking to filmmaker types, we released the site as one of the first BitTorrent-powered products targeting a non-techie audience. And it flopped. As we iterated on the product, YouTube came out, and it was game over :) We stopped working on BitTorrent-related services after that because we had learned our lesson(s), which I’ll recount below.

For consumers:

“I want it now!”

People care about instant gratification. At the end of the day, you’ll have more people watching a fast-loading movie in a small screen than you’ll have people who download the client, then wait an hour or two for the file to download. When we asked people how long they’d want to wait for a download, they’d say “5 minutes at most” even though they don’t understand the quality jump you’re talking about with BitTorrent

“This feels like spyware”

BitTorrent requires you to download a separate client, which is a tall order for non-techies in the world of spyware. It’s just too much work. Whenever we had usability tests that got to a download page, most of our participants would stop. It was too much of a barrier.

“Where are the files? Why isn’t my movie playing? etc.”

And of course, one huge killer in the BitTorrent world is the amount of fragmentation you’re talking about. I think it’s very smart of BitTorrent Inc. to start a destination site, because that’s what consumers want. They want to go to one place, not download the client at one site and find the content at 5 others. Nevermind the problem of codecs (DivX versus H.263 or MP3 versus AAC), which make it so that you can wait hours for a video and then have the frustration of not having the right codec – and don’t expect your average user to know about VLC. So it’s also smart BitTorrent, Inc. is standardizing around Windows Media codecs and DRM.

There are a couple other issues, but this is why Flash is such a great platform for video sharing. You probably already have it on your computer, and you can walk to YouTube and be guaranteed to instantly load and play any video of your choice. Instant gratification without a client download needed, and you just need a site like YouTube to solve the media fragmentation problem.

For content producers, you have your own set of concerns:

Mainstream media has big demands

If you’re working with a studio, of course they have some big demands. First of all, they have all the leverage since they are sitting on the content and you are just another “pipe” to them. So the deals won’t be in your favor, and will be experimental at best. DRM is a must, of course, as is playing nice by not disrupting them in all the ways you could be, which means you’ll end up in a more traditional model. I have to say that still, I’m very impressed with BitTorrent Inc’s ability to sign big studio deals, which I would have expected to take a longer time and more money. Obviously the guys over there are returning their calls quickly :)

That said, one could speculate that part of the reason why the studios would like for BitTorrent to have a LITTLE traction, but not give them full-rein, is that it makes the company much easier to control.

For mainstream media, you are a commodity bandwidth provider

As I mentioned above, mainstream media has big pockets. Obviously Apple just pays a bunch of money for iTunes to function through Akamai, and I’m sure it’s getting cheaper by GB/transferred every day. So ultimately, when it comes to distributing films for Warner Bros, BitTorrent ends up competing with Akamai and the other network infrastructure people, without the differentiation that one of those pure-plays can develop. It’s akin to developing compression software when hard drive capacities are getting cheaper every second, or developing CPU overclocking when you have Moore’s Law. It’s a cool thing to do, but ultimately, it’s a losing battle since bandwidth is a commodity that’s getting cheaper all the time. So the value proposition is much weaker.Perhaps in BitTorrent Inc.’s case, they actually are able to position the “community” as a huge group that builds on the bandwidth value proposition. Even if that’s true, as many people have pointed out, it might be misleading since not that many people actually go to BitTorrent.com to download stuff.

Long-tail content is better, but they care about audience much more than quality

We talked to a lot of indie filmmaker types, and they all thought that our media marketplace idea was really cool – so we got good feedback there. Ultimately though, we realized they thought it was cool not because of BitTorrent, but because it gave them their first way to distribute film outside of film festivals. So they care more about eyeballs, not about the quality of the technology. Even though YouTube video quality sucks, they don’t care because they just want the audience, and if they could publish their content at higher quality, but have a smaller audience, that’s much less interesting. Getting them on board will be cost intensive, since they are very fragmented, but an easier pitch.As an aside, I actually believe there’s an interesting market in the indie filmmaker community that is still ripe for the taking. YouTube is a good first step, but filmmakers have a ton of problems they need solved, from recruiting actors and staff, managing the projects, timelines, and media, as well as the publishing/evangelizing end. If someone’s able to make a consolidated set of tools for this group, it’s probably an important (and strategic) profession to unite. I’ll be waiting to see someone crack this market :)

Conclusion

So net/net, I still love the technology and use it constantly, but there are some major hurdles in trying to commercialize it for the mass market. All of the above lessons were pondered and learned over 9 painful months of tinkering and trying to make something work, and we ran into some problems. Perhaps some company will be able to overcome them.

That said, more than a year after we quit working on BitTorrent-related services, I’d still say that all the above problems still hold. Don’t believe me? Just grab a random smart, but not tech-savvy person, and watch them in silence as they try to get BitTorrent working. They will quit 4 or 5 times during the process because it’ll be too hard. Then set someone else loose on YouTube and you’ll see the difference.

Splitting equity between partners

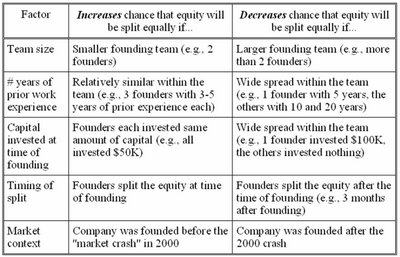

Interesting discussion here: Equity-Split Results: When Do Teams Split Equally?.

Oftentimes, the easiest way to tell how “green” an entrepreneur is comes from their understanding (specifically, lack thereof) on startup equity. I think it comes from the fact that equity is not really a meaningful part of most peoples’ comp in any company other than the rapidly growing startup kind. So you often see conversations (and arguments) about the issues above.

So it may be obvious, but anyone who’s joining a startup should be very careful about what % they are getting, especially if they are joining early enough that they are taking equivalent risk with the founders.

My favorite experience tinkering on side projects has been to have 2 or 3 founders at most, all of them technical enough to prototype and code, but one focused mainly on business-y stuff (logistics, organizing, legal, etc.) and the others focused mostly on development. The worst dynamic, in my opinion, is when you have a pure business guy and a developer (or two) and the business guy spends all his time making projections and/or bossing around the developers with crazy visions :) It’s best if everyone works on the product and no one person has a monopoly on the vision or the customers, at the very beginning of a company.

Either way, I’ve generally thought to split equity equally when everyone is taking about the same risk, particularly before the company has made any money. After all, joining a month or two later is not necessarily a big deal if the person who’s joining is worth it and deserves co-founder status. Otherwise, a couple percentage points here or there can create animosity that ultimately interferes with the success of the startup (which is hard enough as it is).

Simplicity and choices for users

I’ve been following a pretty interesting discussion that’s been happening about the new Start menu on Windows Vista. You can see it below. See anything weird?

Well, Joel comments: Choices = Headaches.

Then, hilariously, one of the guys who worked on Windows at Microsoft (and now is at Google) comments on how it ended up this way.

And of course, finally, this is how the Mac OS X shutdown process ended up happening, from an Apple guy.

It reminds me of a discussion in Designing Interactions about the “Zen of Palm” and how important it is to make things easy for the user based on what they want, rather than a big menu of items. Here’s an anecdote:

If you think about the way your desk is organized, you have some

things on your desk, and some things in your drawers. Why is that?

The things on top of your desk are there because you want to access

them very frequently. Imagine if you had your mouse, or your phone,

or something that you access very frequently, and you put it in your

drawer. Every time you wanted to use it, you’d have to pull it out of

your drawer. It might be only one more step, and it might be only

one second, but it would really drive you crazy over the course of a

day.

Think about your stapler and staple remover. My stapler is on top

of my desk, and my staple remover is in my drawer. The reason is that

I staple papers more frequently than I unstaple them. You can argue

that architecturally speaking the stapler and staple remover are

equivalent and therefore should be in the same place. If you look at

it intuitively and ask what you do more frequently, some of these

decisions just naturally bubble up to the top. It all depends on

understanding your customers, but not on a very complex level. It is

not rocket science to suggest that you would be more likely to enter

a new phone number than to delete one.

Anyway, I’m sure the start menu ended up the way it was, described as “the lowest common denominator” because it presented all the possible options, “logically,” rather than needing to make choices about what a user really would want.

Just switched to Camino…

A friend just pointed out something that should have been blindingly obvious: Firefox is slow, and if you use the same engine with native Mac libraries, things are much faster. So if you use a Macbook, download Camino.

There are a couple things I miss, here and there, but overall it’s great. I miss the spellcheck squiggle that’s in Firefox 2.0, as well as

The funny part, of course, is that I’m complaining about slow Firefox is when there are worse browsers out there.

Federated Media’s business model

Valleywag notes: Federated Media client losses.

For folks that don’t know, Federated Media is an ad repping firm. If you are a publisher, you can give your inventory to FM and they will sell ads against it. This is different than an ad network because they are transparent that they are selling your ads on your site. An ad network will often stick you into a blind category, like “Tech” or “Automotive” or something similarly broad. Also, rather than paying you a CPM and arbitraging the ads, instead the ad repping firms take 20% (or whatever) right off the top as commissions. Think of them as an alternative to hiring a bunch of ad sales people.

The great part about the FM business model is that they can focus exclusively on higher-quality sites. Rather than working with all the remnant inventory sites that lack focus and have editorially-problematic content, instead they can focus on sites that have branding potential, and thus, deliver higher CPMs. So you’ll see them delivering CPMs in the $5 to $20 range rather than under $1.

The bad part is two-fold: 1) Channel conflict and 2) High/low CPM squeeze

Channel conflict is created once the publisher gets too big. Basically, once the site is successful, then ad agencies will start approaching the site, and the site will want to hire a direct sales team. Of course, this creates competition if an advertiser can buy ads from two different places. So usually what happens is that if the ad sales can be brought in-house, they often are.

The high/low squeeze comes from the fact that ad repping firms can work with sites that are high-quality, but not TOO high-quality. And of course, they can’t work with low-quality sites where automated approaches dominate. In that case, there are just plenty of sites that aren’t high-quality enough, brand-wise, to justify a human (rather than automated) sales team. This is the purview of the remnant ad networks.

Anyway, those are the pluses and minuses. If I have time later on, perhaps I’ll write something about where FM could extend their business model to get around these issues.

Product versus Experience

Fun little analysis at Information Arbitrage: Joe, that little coffee shop: Starbucks Beware.

As many people are aware, "product design" and "product management" and "product marketing" are all becoming obsolete. The reason is that EXPERIENCES are starting to dominate the conversations that once was about products.

Take software, for example. If you thought of the actual bits and bytes as your product, then you might focus on making sure the right features were in place, that the technology was reliable, and all those other good things. That’s great, and that’s served the industry well for decades.

The problem is that people don’t CARE about your product. They just care about their problems. So when you think about the bits and bytes as your product, in fact you should be a lot more worried. The EXPERIENCE cycle for the customer starts, in fact, before they are a customer. They might include things like:

- The first time they hear about your company/product

- When they here an opinion from a trusted source

- If they go into a store selling your product and look around

- When they see the packaging

- Or if your product is a website, when they see a blogger link to it

- Then, when they use your product, what happens

- After they try your product out, what they say to their friends

- How you charge them for the product, and how that interaction goes

- If they have problems, how that gets handled by your company

- What the product allows them to accomplish, and how that feels

- How people interact with your customer after the product gets used

- After they use your product for a while, and think they need a new one

- … and the cycle goes on

Either way, this customer experience is obviously a lot more important than the product, which might really traditionally encompass one or two lines of the cycle described above.

So the coffee story is a good one, which really reminds tech guys like me, who obsess over things like "product differentiation" and feature checkboxes that there are many industries – particular CPGs – where everything is a commodity and people buy based on things other than features. Instead, focus on what the customer wants, and maybe that’ll mean less features (but hopefully the "right" features).

Another great example, other than coffee, is Chinese restaurants. Whenever I go to Chinese restaurants, I inevitably talk about the same thing. Most restaurants run by Chinese immigrants tend to be in a race to the bottom, when it comes to pricing. Then you go to a restaurant like PF Chang’s. The one here in Bellevue has a hour-plus wait anytime of the week, and they charge more and the food is mediocre. But it works because it has a great experience (other than the wait), where the location is convenient, the decor is very upscale, they hire servers that resemble the customers, and that gives them the ability to price higher than any normal restaurant. Again, it’s not about the food, it’s about the experience.

Autmated models versus human experts

Check out this interesting discussion here: The Perfect and the Good. It’s a discussion by Malcolm Gladwell on using automated predictive models to calculate what kinds of revenues a movie might generate, just based on factors like the actors, the director, the genre, etc., all coded up as a mathematical equation. After he wrote about this topic, a bunch of people pointed out all the flaws involved. Pretty interesting.

Malcolm Gladwell’s response, which you can read in the link above, is that predictive models are often better on average than humans, but usually not better than the best human. Very true.

It reminded me of a pretty cool paper published at Legg Mason on the nature of expertise titled, Are you an Expert? I highly encourage you to read it.

Within the paper, they had this great diagram. Simply put, humans are better at computers at different things, depending on the problem domain:

Flash will dominate the media-sharing web

Funny to see someone else notice a growing trend: The Coming Flash Desktop. Since YouTube came out, it’s been pretty amazing to see the usage of Flash grow and dominate media sharing on the web.

I remember that back in the day, Google Video required you to actually download a program that would need to run on your computer. And you had a bunch of sites like Break.com (formerly Big-Boys) and Putfile using embedded Windows Media Player controls. But now, pretty much everyone has switched to Flash.

A close friend, Will Portnoy and I lamented the fact that we couldn’t buy Macromedia separate from Adobe and cash in on this trend. We noticed this because we too, stupidly, were trying to commercialize another technology and make it more mass-market friendly: BitTorrent. Anyway, we eventually learned that being on 95% of the desktops and bringing instant gratification was just a one-two punch that’s very hard to overcome with any technology.

The question is, what’s next for Flash? If you imagine that the folks at Adobe are not asleep at the wheel, they could do a lot of interesting things that would make their company very interesting.

Here are some of the random options:

- Building a P2P protocol into the architecture (obsoleting quite a few companies)

- Making it easy to "register" your media into a central media directory, which they could control and syndicate

- Building search or other functions into the media framework, or providing services to unite all the Long-Tail content

- Making it easier to embed Flash and use it in rich applications beyond websites

- etc…

Either way, it would not be particularly hard for Adobe to get their hands on a ton of content, based sheerly on the fact people are building applications on their proprietary framework.

I figure that Adobe probably has a couple years to do this before a bunch of people freak out and decide to collaborate and use an open standard :)

Cargo cult science

Ever heart the term cargo cult science? Richard Feynman made a famous speech about it. Basically the idea is that science is not merely the numbers and analysis and jargon, but really hinges on a philosophy on scientific investigation. One should be very honest and try to find the truth, not argue some point at the expense of honest scientific dialog. I’ve often seen the term used when describing the science that accompanies court cases, or political discussion :(

Anyway, the term come from the "cargo cults" of the Pacific islands, where natives would set up fake airplane runways and radio towers in an effort to get a Jesus-like figure, John Frum, to send cargo planes. This stemmed from their understanding that they were behind (without cargo) because of a lack of magic or ability to conjure it, rather than because of technology/knowledge/whatever. Anyway, here’s a good overview of the phenomenon: The last cargo cult.

Happy thanksgiving!

For your entertainment as you eat turkey, please read this cute story: Wikipedia Brown and the Case of the Captured Koala.

I love it… more estimation error for Internet stats

From John Battelle’s must-read blog: Fun Stats for The Holiday.

He has the following image, which tells you how 3 different providers of stats give you crazy different numbers:

Who’s really right?? We’ll probably never know. It would be great, of course, to see Alexa’s take on this, but I think comScore/NNR/Hitwise in this case is actually counting searches specifically, rather than just raw pageviews.

For people that are interested anyway, here’s the Alexaholic comparison of Google+Yahoo+MSN+Ask+AOL, which shows a HUGE bias towards Yahoo (albeit declining) and MSN and Google duking it out. As I mentioned before, this should be taken with a grain of salt:

IDEO Method Cards

Cool! I just bought IDEO Method Cards. The idea is that you have a bunch of these cards that prompt you to think about the user in different ways – for example, one might ask you to imagine "A Day in the Life" where you think through the user’s day to give context for how they use your product. Another might be a "Mind map" where you brainstorm a bunch of concepts and make a diagram of how they are related to each other. This might help you group like-concepts and discover relationships between people, experiences, and emotions.

Anyway, it may be that people with a more intuitive understanding of people don’t need things like this, but for me, I tend to be a bit more on the abstract side. Hopefully this will help me get more specific in thinking about users and what they are going through in and around the product experience I’m trying to create for them.

More info on the method cards at Businessweek. I first encountered this concept while reading the excellent nerd-history-meets-methodology book Designing Interactions, written by Bill Moggridge, a co-founder of IDEO.

I don’t usually do this…

I don’t usually pimp out sites, but I saw this one and really liked it: Wesabe. I’ve been looking for a quicker, easier app to use other than Quicken or Money, where it seems like I end up spending hours getting my data in and classifying expenses. I think there are some really interesting ideas here.

Of course, as an advertising guy I think, wow, if people were comfortable enough sharing their info like this, then you could get a lot of revenue based on offering coupons (i.e. ads) based on peoples’ purchase histories. Anyway, it’s a slam dunk business model, if they can get scale and adoption.

I’ve also been thinking about the entire self-help/self-improvement market as a whole, and see some really interesting opportunities there. Consumer motivation coupled with a fragmented market equals something interesting. I think sites like Wesabe are only step 1 in this evolution.

Anyway, for lazy people, here’s the tour video:

Problems facing hit-driven media, from the gaming perspective

Saw this interesting presentation today: Age of Dinosaurs.

For those of you not interested in gaming, just scroll down halfway through where he starts talking about the value chains within lots of different media industries. It’s fascinating to see the games industry hit the same wall as all the other media – between digital distribution, long tail effects, and the breakdown of the taste-making gatekeeper types, you see the games industry hitting a pretty major wall in the next couple years. It’s been fascinating to read about this in conjunction with what’s been happening in the music industry.

It was also interesting to see the content creation costs go up while the hits do not. I’ve seen a graph like that in the past, and it was about drug development. As I understand it, it’s becoming more and more expensive to create new drugs, whereas the actual number of drugs that are getting through to FDA approval (and thus become "hits" in the hit-driven world of medicine) is staying about the same. Supposedly, it’s only going to take a decade or so for the model to get so messed up that making money will be pretty tough.

Either way, it’ll be very difficult to see this shake out – I suppose there aren’t too many levers to pull on the media side. You just have a couple options:

- First, you can focus on the revenue side. I doubt that you can find more money by promoting the "hits" so I assume it’ll come from Long Tail media within established channels. This would mean you expose people to more of the niche stuff, and maybe people will start buying that.

- Related to that idea, perhaps you can carve new media genres out and find some hits in

there. Many folks have observed that there’s a huge trend towards "media fragmentation" out there – whereas 50 years ago we had 4 channels, now we have hundreds or thousands, plus Internet, plus XM radio, plus all that stuff. So maybe within a big industry like gaming, certain sub-genres form, then grow bigger, until they create mainstream categories themselves - Another option is obviously to focus on cost. So if you can help carve down the pipeline that it takes to create this content, that might be useful. It’s funny that user-generated content, for example, has emerged as a worthy way to create destination sites rather than paying a bunch of writes, photographers, and designers to create the site for you. Perhaps other methods will emerge to make generating content easier/faster

I think ultimately, all of these approaches will work, and you’ll see focus on each method. That said, I’ll be keeping my eye most closely on the fragmentation of media and how these fragments grow and take on lives of their own.

Making functional apps more fun!

Wow, what a trip – it turns out an author I love has actually been writing a lot about the intersection of game mechanics and functional applications. Here’s a summary covering what she cares about: How Game Mechanics Can Make Your App More Fun. And here’s a great Powerpoint detailing the ideas: Shufflebrain slides.

I originally read Amy Jo Kim’s book called Building Communities back in the day, which I often cited in nerdy conversations with other tech people. So it’s interesting to see her develop more concrete ideas than I have on something I previously thought was pretty original :)

Anyway, read her examples – seems like much of it comes from eBay, MySpace, and Flickr. Those are obviously companies with very strong communities that have been able to exploit a couple game-like mechanics on their sites.

Definitely worth reading!!

Looking to connect with game designer types?

Hi everyone – I’m looking to meet up with some game designer types. If you are one or know of any, please get in touch with me at voodoo [at] g mail [dot] com.

In particular, I’m interested in the fact that game design is partly the creation of incentive systems to get users to move along a certain path, and give them enjoyment at the same time. You could imagine applying that general technique to a variety of different applications, not just games.

Anyway, please send me a note if you know anyone like this. (And sorry for the light blogging, I’ll get back on the saddle in the next couple days)

Designing for other people versus designing for yourself

I had lunch with a very smart and capable friend of mine, Max, today. Max, myself, and a couple other friends co-founded a student group back in college, SEBA (formerly SBE) which we grew from scratch to over 500 students.

Anyway, we had a conversation about starting companies and the difficulty of designing for customers that are dissimilar to you. In particular, Max was against it :) He said he’d much rather stick to hobbies and activities where he had direct intuition to make decisions.

It’s a very valid point, and a huge hurdle for entrepreneurs that are targeting contrarian demographics. For example, a bunch of 30-year olds targeting the seniors market, or Americans trying to target overseas audiences. I imagine many folks are building social networks that are exploring these different markets, with some level of difficulty.

On a personal level, I’d say that the projects I’ve worked on to target audiences other than myself have also led to the most humbling outcomes. After thinking you "grok" a target customer audience, when you show them a prototype of your product and ask them what they think, be prepared! In my case, I got a bunch of very humbling feedback that indicated I had a long way to go. Better to get this information early than later, of course.

Accelerating user risk

In fact, you could argue that as you get more and more removed from the user, the risk you are taking that your intuition won’t match the target audience accelerates. Here’s the range of possible scenarios, from best to worst:

- Being the customer

- Having a business partner who’s a customer

- Having a good friend/significant other who is the customer

- Talking to the customer intermittently

- Knowing of the customer and learning indirectly

- Don’t talk to the customer

I think as you remove yourself from daily, in-person contact with the target audience, you take on a ton of risk. Mitigating this risk is a big problem, and you’d have to talk to companies like IDEO and such to figure out how to handle this. Most likely, there’s a lot of effort that would have to go into interacting with customers that you could generally skip by building tools for yourself.

A rule of thumb on user risk?

As a corollary to this, I’ve speculated with my friend Dave about how you’d go about funding pre-launch Web 2.0 startups. Ultimately, we agreed that the co-founders would need to represent the target audience for the company – that’s the only way you can reduce some of the risk from initial user behavior.

In fact, I wonder if the personality of an entrepreneur inherently makes it harder to be empathetic to different types of users. After all, part of doing a startup requires a bull-headed exercise in reality-distortion where you ignore a lot of social convention. The ability to do that may be inversely proportional to actually listening to people :)

Anyway, I’d certainly like to work on applications outside of my direct audience, but clearly I will have to think more about how to regularly listen to and incorporate feedback from a multitude of different people.

Geniuses versus very smart people

Nice article about Kevin Murphy, a UChicago economist: Murphy’s Law.

My favorite quote:

When Murphy won the MacArthur, a writer for the GSB student paper asked

him how to distinguish between a genius and a really smart person. “A

really smart person will come up with what you would come up with,”

Murphy answered, “only faster. A genius will come up with something

that you would never come up with, no matter how long you worked on it.”

I know a couple people like this, and it is amazing when you see them tackle a problem. It becomes immediately clear that you could have spent months or years on the problem and wouldn’t have gotten to the same novel answer.

Are you misusing Alexa numbers? (Probably)

I’ve been using Alexa for over 2 years now, and it’s been interesting watching the myriad of different ways that people misuse and misunderstand the numbers. For work, I’ve had to use them in conjunction with Nielsen//NetRatings numbers, comScore numbers, and others.

To start, here’s what Alexa writes about their stats… as an aside, if you have quoted Alexa numbers or sent around charts without knowing the following info, shame on you :)

In addition to the Alexa Crawl, which can tell us what is on the Web,

Alexa utilizes web usage information, which tells us what is being seen

on the web. This information comes from the community of Alexa Toolbar

users. Each member of the community, in addition to getting a useful

tool, is giving back. Simply by using the toolbar each member

contributes valuable information about the web, how it is used, what is

important and what is not. This information is returned to the

community with improved Related Links, Traffic Rankings and more.

The gist of this is, all the information comes from a bunch of toolbars that monitor what users are seeing, and then send it back to Alexa.

So here are a couple issues with Alexa numbers that you might not understand:

Alexa doesn’t give pageviews or uniques

When you pull up a particular domain and look at their traffic stats – for example, let’s say Digg.com – it’s easy to think that the number 10,000 somehow means that Digg is reaching 10,000,000 people (or whatever). It’s not. What that means is that for a million toolbars, you have 10,000 people who have seen it in the last day. That’s what "Daily Reach (per million)" means.

The number of toolbars in a million that see a particular stat is pretty meaningless. It’s certainly accurate, but there’s very little meaning that can be assigned here, other than relative meaning. In fact, you can think of Alexa as giving you a pretty weird proxy of the actual stats that you care about. It’s akin to asking "How many people are in the United States?" and answering with "There are 600,000,000 baseball hats in the United States." You’d hope that the two would correlate, but sometimes they don’t.

There are a lot of smart people whose jobs are to know how many

pageviews a particular site has. Advertising media buyers need to know

in order to make sure they are buying ads on sites that are big enough

to even be worth picking up the phone. They don’t use Alexa. (More on

what they DO use later)

Alexa’s numbers are based on a biased sample

Do you run an Alexa toolbar? If you are reading this blog, probably not. Instead, you probably run Firefox, you are more likely to use a Mac, and are probably involved in the advertising or startup world. That’s the particular bias of this blog.

In fact, you might ask, who has an Alexa toolbar? I don’t know the answer to that, but it’s an important one. Those are the people generating stats for the Alexa site. I would guess that pretty unsavvy users typically download the toolbar, for random features like popup blocking or whatever, rather than a general distribution of users. Or more precisely, the toolbar is weighted towards Windows users that actually download the Alexa toolbar and find it useful enough to keep it around. In fact, it probably has a lot to do with whoever Amazon/Alexa has cut deals with in order to distribute their software.

Another issue: Remember that this is all tied to the toolbar, not to the user. So if multiple people use a computer, then you’ll have lower numbers in the "uniques" count. For this reason, you’d expect that certain kinds of sites might be undercounted in the Daily Reach stat, since a bunch of people will only count as one person. For example, students and younger folks might be more likely to share computers. Or heavy travelers, that are more likely to use internet cafes and such. These groups might all be counted as one person, rather than all the collections of folks that use a single browser.

Sound trivial? Well, these are the kinds of precise numbers that media companies have to deal with every day. For example, a lot of Hispanic-targeted sites report lower numbers than usual – the general theory is that some of those niche sites count fewer at-home or at-work users than others. Many of their users are coming through libraries, cafes, and other shared computer environments, and that affects millions of dollars of ad revenue. It’s very hard to correct for behavioral stats like these.

Alexa gives false certainty

When one site seems to be significantly outperforming another, you really have no idea how that really compares from an Apples-to-Apples comparison. If you look at it from a pageview-to-pageview comparison basis, there’s all sorts of uncertainty there that isn’t exposed in those precise, one-pixel line charts that Alexa spits out. In any sort of actual statistical treatment, you’d have confidence intervals and would invalidate data from sample sizes that are too small. (The 100,000 ranking mark in Alexa seems a bit arbitrary, don’t you think?)

I’m sure many startups (and others) are losing millions of dollars in valuation based on some VCs looking at their Alexa stats and being disappointed. Or they are being compared to their competitors and it looks like they are being creamed. Either way, they are misinterpretations, because it points to the idea that objectively one site is better than another – and that’s a false certainty. Remember, there’s lies, damned lies, and statistics :)

Alexa is the equivalent of bad exit polling. Perhaps worse, because at least exit polling typically has confidence intervals. Imagine if you compared two small sites on the Internet, and one seems much higher than the other. Would you still conclude this if you knew that the data was under 90% significant? As in, you could only use it on a directional basis? Either way, be smart about the way the numbers are being used, as to not interpret a rank of 2,000 as a "sure thing."

How do we get better data?

So one question is, if not Alexa, then where can you get better data? If you look at the media analytics business, dominated by Nielsen and comScore, you’ll see an industry where this kind of data needs to be methodologically sound enough to drive billions of dollars of advertising spend.

Right now, Nielsen has the cleanest reputation for these types of metrics. A year or two back, when we talked to a lot of large New York brand agencies about whether they prefer comScore or Nielsen, everyone said Nielsen. Typically, Nielsen is considered to have better methodology, so that the data you can get from them is more trustworthy. That said, often the data you get from them is sparse, so you go to comScore which gives deeper data.

How comScore gets data – still biased, but better

Here’s how it works: comScore has little desktop apps too, which monitor user browsing behavior. They go out and buy lots and lots of remnant advertising to get people to install the things, so they have a massive "panel" of users to figure out what they’re searching on, what websites they are visiting, and so on. They have a pretty huge panel, I believe 500,000 or so users, and they show data on top of that. Note that even though this is a big group, it’s still inherently biased. Who clicks on banner ads and installs random apps onto their computer? They can do some normalization to account for this, which makes it better than Alexa’s approach, but it’s still not great.

The upside to having this huge panel is that they can give lots of detailed data about the web. They can give you a wider index of sites people are visiting, queries they are searching, and so on. Sometimes you don’t care about relative strength, you just care about getting this sort of raw data. For example, a lot of leadgen and advertising companies just want to mine the comScore data for popular queries, so they can buy cheap ads to drive more traffic to their site. Or domainers might be lots of mistyped domains to get AdSense traffic.

Nielsen’s old-school approach yields balanced numbers, but less detail

Nielsen has always tried to have a more balanced approach to their panels. This is a huge part of their brand and reputation. So to start out with, in their most traditional panel, they are actually doing old-school random-digit dial in order to get people on the phone. They are literally generating random phone numbers, talking to the people, and getting them to answer a survey where they recall a bunch of sites. That’s the basis of their @plan service, which drives over a billion dollars of media buying online.

The only problem with this approach is that there is less detail that can be collected. You wouldn’t expect people to be able to recall dozens upon dozens of sites they’ve visited, and you wouldn’t expect them to tell you all their recent search terms. Plus, this might bias towards larger sites where people recall their names better because of brand, even if they don’t actually visit those sites. Self-reporting sucks for lots of different reasons, just ask any usability or market researcher.

In order to address the detail issue, they also have a separate product, called MegaPanel, which also has a desktop app based approach (similar to Alexa and comScore). It’s pretty much the same thing as I mentioned above, and they have reached hundreds of thousands of households in their panel.

Normalizing biased samples to fix data

Both comScore and Nielsen do some "normalization" in order to fix up the data, since they are getting a biased panel of internet users. This happens by saying that if 80% of the panel users are women, but in real life, the internet population has 50%, then they will discount all the stats from the women part of the panel to get it down to 50%. That way, women won’t over-represent the panel.

They do this across a bunch of different dimensions to normalize their data into something that fits an overall Internet demographic. That way, their data should come out more representative. If you don’t normalize your data, then lots of random groups will be over-represented, and you’ll see a lot of bias. In my experience, I’ve seen a lot of this data bias towards middle-aged women. Who knows why? I’d guess that they are the most likely to download these sorts of data collection programs without knowing any better :)

This normalization works reasonably well, but there are still big problems since estimating 100MM internet users based on 100,000 internet users is still difficult, especially when you are making big adjustments based on little percentages here and there.

Behind the scenes, communication happens

Of course, because lots of money is at stake with comScore and Nielsen, they also do a lot of work behind the scenes with the publishers and advertisers to make sure everyone is happy. When you have big outliers like the portals, or ESPN, or otherwise, sometimes the data can seem off. Well, a billion here and a billion there, soon enough you’re talking about a lot of pageviews.

So a lot of times, comScore or Nielsen will ask the companies how much they are seeing internally from their ad servers (which are the only REAL source of information) and then adjust their numbers manually based on that. This obviously completely circumvents the panel philosophy, but sometimes it’s needed to reflect what’s really out there.

In the end…

Either way, use Alexa numbers for what they are: Rough proxies. Realize that they are a reasonably flawed way to compare things, and especially for lower-ranked sites, are messy and biased. Don’t reach serious conclusions without talking to the sites first to see what stats are coming out of their analytics packages, and seriously consider caveating any speculation. If you’re in the business of making real decisions based on this data, you should probably shell out the $40k/year or so to get better data.

Good moves for brand ad networks

This is a very smart move for Spot Runner: Spot Runner Gets Media Investment. For those of you that haven’t heard of them, the company is a very interesting cross between online and offline advertising. Basically, they have an online interface where small to medium advertisers can create TV commercials on the cheap (think templates, stock video, voiceovers, etc.), and then they handle buying from local stations to drive down the cost.

They are part of a fascinating trend of leveraging online strenghts in aggregation and automation, and then applying them to offline channels. NextMedium is also in the same functional category, for product placement. DS-IQ is such a company for outdoor/digital signage, and dMarc is such a company for radio.

Anyway, since obviously TV is most brand focused (minus those 1-800 infomercial or Girls Gone Wild type commercials), it’s clear that Spot Runner needs the support of a lot of brand advertisers to make their business viable. What’s a better way of doing this than getting one of the world’s largest brand agency conglomerates to buy a chunk of your company? Spot Runner is doing all the right things to build those deep, Midtown Manhattan relationships… other companies focused on brand advertising (in particular all those video ad networks) should watch them to learn a thing or two.

Nice interview

Link: QA with Moneyball author and sports economist.

Interesting interview with one of my favorite authors, Michael Lewis. (BTW, light on blogging these days since my MacBook Pro is out for repairs on the right fan)

Winners don’t quit, and quitters don’t win…

Link: YouTube: From Concept to Hyper-growth. (Text summary here)

There are a lot of interesting bits to the YouTube story, but this paragraph was my favorite:

Problem was, nobody used YouTube. Karim shows another video of the

YouTube boys sitting around pondering their existence. Nobody’s going

to watch this, they complain; “This is lame.” To try to attract

viewers, the three figured the best thing would do would be to get hot

chicks involved. So, Karim recounts, they posted an ad on Craigslist in

Los Angeles promising attractive females $100 if they’d post 10 videos

on YouTube. They got not a single reply.

I’ve been in exactly this mood with my friends, working on little side projects, and let me tell you – it sucks. It calls into question why you are doing what you’re doing, and it makes you wonder if your fundamental assumptions are wrong. It’s a dark moment of self-doubt. Honestly, it’s even worse when you feel like you’re leading a team, because the other guys are depending on you for vision and instruction, and it can be easy to feel like you’ve let them down.

But the important part to realize is that EVERY business goes through this stage. You always go through a step where, after a tremendous amount of hard work and inflated expectations, you watch your baby take its first couple steps. And almost consistently across the board, the first phrase is very rough. That initial traction comes from a very small group of people, the early adopters, who are the only ones who are willing to use your site without any references or recommendations.

Especially in a community site, where you need to solve a chicken-and-the-egg problem of users versus content, it’s hard to get the flywheel turning.

And just as every startup goes through this stage, the way out is almost always the same – if you did your job in the concept formation, meaning that your target market has been identified and they actually like your product, then it just takes a lot of sweat to get the flywheel turning. You have to get into the channels where your users are, expose them to your shiny new product, and go from there.

A lot of that can seem like low-value work. Rather than coding or strategizing or building, instead you are doing the Internet equivalent of standing on a street corner handing out flyers. But this "feet on the street" step is what’s necessary to get that initial traction. So spam those mailing lists, post in those forums, e-mail all those little blogs. Post your own content, lots of it. Get your friends to do the same. Otherwise, you won’t ever get past the zero audience stage.

PS. It’s hilarious to me that to find hot chicks (since of course, they don’t know any personally), they decide to post something on Craigslist of all places :)

Big news: I’m moving to Silicon Valley

Many of you that know may might find this news completely unsurprising, but I am leaving for Silicon Valley at the end of the year!

It’s both an exciting and bittersweet event for me – as a life-long Seattleite, I’ve grown to love the city and all the casual, low-key values it represents. Being local with all my friends and my family is an immensely rewarding thing. And on a professional level, I’ve been proud of our work at Revenue Science, where we’ve created a rapidly growing, dynamic, company. Only a couple years ago, we had a mere 2 media clients – now, we have dozens of top tier publishers like WSJ, ESPN, Washington Post, and a ad network that went from 0 to multi-billion impressions per month in just 1 year.

That said, I’ve always wanted to move to the Bay Area for the opportunities it represents, and for the like-minded people that I know there.

My last day at Revenue Science will be November 30th, at which point I’ll have to discover and decide on my new gig. I’m looking to found a new company or potentially join a very early stage startup. Should be a lot of fun to figure out where I’ll be in a year.

New metrics for social media sites?

Jordan, a fellow Seattle tech guy, asks: Any comments on this? The New Media Audience Measurement Business Model Conundrum.

Well, Jordan, the problem is – metrics like CPM and CPA aren’t meant to measure how users "connect" with brands – they are simply economic metrics that capture media spend. Beyond CPM, there are other rich metrics that advertisers use, such as demographics, targeting, frequency, pageviews, etc., to measure the effectiveness of a brand sell.

You can see an example of ESPN’s cross-channel media kit, and their research on audience metrics. Sometimes as part of this, people do brand studies like brand recall, message association, etc., with companies like Dynamic Logic or Insight Express.

Thinking that "brand connection" metrics can somehow revolutionize brand advertising points to a serious misunderstanding of the brand advertising industry. Much of brand advertising is NOT based on metrics. No single set of numbers can ever change advertising agencies’ minds about where to buy media, without the human relationships to match.

This is really part of a long pattern of techies encountering different cultures and then assuming they can apply their own techniques to it. For a techies, the numbers are everything – they seem objective, and correct. Surely no one can argue with numbers, can they? So with things like brand advertising (and potentially their love lives), techies want to boil things down to numbers, and argue from there. But that doesn’t always work, and that’s why many techies are single. (Turns out asking girls’ their SAT scores doesn’t always work)

For example, if a social network were able to show X brand engagement points for a financial audience, and X was larger than the metrics for a well-branded, established site like Wall Street Journal, a logical viewpoint might be that a social network would command a higher CPM. But really, that scenario will never, ever happen. Wall Street Journal will always command more dollars based on their reputation, and relationships, until new media companies are able to establish those. (And doing this involves buying lots of steak dinners, not showing people "metrics.")

As for as advertising goes, Web 2.0 is not special. Get over yourselves, guys. Media companies will figure out ways to incorporate social networks as some % of a multi-hundred million dollar advertising budget, and they will try and buy using common metrics across all their publishers. That’s the way it works, and no amount of Ruby on Rails will fix this :)

In my opinion, Web 2.0 companies need to figure out how to speak the advertising language, and figure out how their websites support what advertisers are trying to do. Connect with the current flow of money, NOT make up new metrics that are hard to understand. That should be the goal.

Unclear definitions for click fraud

John Battelle comments on a recent click fraud article in WaPo: WaPo Does the Click Fraud Piece, I Scratch My Head….

I’ve been following the click fraud discussion for a while now, and it’s a emotionally charged topic because advertisers feel like they’re being cheated. One problem that’s complicated the discussion is that people simply don’t agree on the definition of click fraud – in fact, there’s really a huge spectrum of different practices that would or would not be considered click fraud.

Here are a couple definitions of click fraud, from really clear to cloudy:

- Building a bot to click on your own ads automatically

- Clicking on your own ads to drive revenue

- Encouraging users to click on your ads

- Users double-clicking on ads

- Having a confusing user interface to drive fake clicks

- Accidental clicks from ads being too close to content

- Placing high-value ads on unrelated content in hope of clicks

I think most advertisers would consider most, if not all, of these practices click fraud. The fact is, each one of these bring in users who may be uninterested in the content behind the ad. These "unqualified" leads result in lower conversion rates, where advertisers end up footing the bill.

Publishers and ad networks, on the other hand, probably view everything after double clicks as fair game. Their definition of click fraud is much more technical in nature – as long as it’s not someone consciously committing an act of fraud, from their perspective, nothing has happened.

The truth of all of this, however, is that advertisers don’t want low converting ad spend. So if that’s caused by a ad-clicking bot, or by clicks from confusing UI, it’s all considered bad. In the long run, the only way to solve this is to implement the sort of "smart pricing" that Google does, to drive a more consistent cost-per-action. This means that, over time, ad networks will start to gravitate towards this CPA model since it gives more consistency for advertisers.

IDEO on urban design

One of the best articles on IDEO I’ve read in a long time: IDEO’s Urban Pre-Planning. Don’t forget to click on the pretty pictures on the right side!

It impresses me greatly that an approach for experience design and innovation can be as generalizable as what IDEO has. Anyway, read the article to get more info.

Coin-flipping contest

Link: The Top Pickers vs. the Pack.

If you held a coin-flipping contest with thousands of people, and had them flip coins over and over again, eventually you’d find one or two folks who had a long string of heads. Then, if you were to ask them how they did it, they might even have cogent explanations on how or why they had become coin-flipping "experts." At the end of the day, their ability to flip coins would still be 50/50, like everyone else.

The funny thing is, the model for PicksPal and the companies discussed in that article come from simply SELLING the predictions. So like mutual fund companies that keep thousands of funds around just to publicize the occasional winners, their interests are not aligned with yours. They just want you to transact (and buy picks), not actually participate in the winnings themselves.

When you see these companies actually investing their own money into the results, then that’d be the first indicator that the company believed the results were any good.

Ironic article about math

Link: Confident students do worse in math; bad news for U.S.

It’s always sad when journalists confuse correlation with causation, but even worse when they’re writing a story about math and they get it wrong!

The article states that confidence about math and the actual ability to do math seem to be inversely correlated. Then it enters a conversation about how making kids enjoy math and acts like confidence has anything to do with the resulting mathematical (in)ability.

As anyone with a basic understanding of logic would understand, a correlation between the two doesn’t mean that tweaking one will affect the other at all. It may be some third variable (oh, let’s say, constant scholastic competiton) that is causing the two. If the competition is high, then that could lead to both high performance and low self-assessment. The next step in this study would be the measure some of the variables and then try to assess causation.

This reminds of a common observation that attractive people are often insecure about their looks. It is because they are insecure that they primp so much :)

Inventory glut in social media

Worth reading for any internet ad junkie: Yahoo! Q3 2006 Earnings Call Transcript.

I will talk about the inventory glut. It has definitely been a huge change. You can see from the page views of a lot of the social media sites that exist today. That is going to change the market dynamics. What we hope is that it is going to bring in whole new categories of advertisers who have been focused mostly on the search side to be able to bring them to the other side of the kinds of advertising that is capable.

An interesting point is what a "glut" really means, in this case. Obviously it has to do with supply of ad inventory outpacing demand, but what kind of supply and what kind of demand? Well, according to Yahoo’s COO, the glut is being caused by the pageviews generated by social media sites.

But let’s dig into this deeper: As far as direct response goes, there’s no such thing as too much supply. For most direct response companies out there, they can precisely calculate the amount of money that is earned when a user visits their site and performs an action. Then they do the math to calculate, backwards, how much they can spend on an ad, in order to break even. As long as they satisfy that minimum, advertisers will spend as much money as they can get their hands on.

So ultimately, a glut implies one of the following scenarios:

- Either, they don’t know how to efficiently monetize remnant inventory well, using direct response techniques…

- … Or, they have so much inventory they can’t get brand advertisers to absorb it all.

In scenario #1, that means Yahoo has a clear weakness in technology, manifesting itself as an inability to squeeze money from social media sites. Otherwise, if every Flickr pageview could monetize like a Search pageview, they wouldn’t call it a glut – they would describe it as a huge opportunity. Obviously this doesn’t bode well for a company that spent 1/3 of their Analyst Day this year focused on how to incorporate social software into search and a bunch of other products. It could be that Yahoo is helping create a huge number of low-value impressions that they don’t know how to monetize.

As an aside, this problem of monetizing context-less inventory is a really big opportunity for advertising companies out there. Outside of the 5% of so of our day that’s spent on search, the rest of those pageviews go to random internet browsing, communications media like e-mail, IM, etc., and other low-context activities. Obviously, any company that’s able to figure out how to bring context into those areas, and help "irrigate" the Contextual Desert has a huge opportunity ahead of them. (I happen to work at a company which does such a thing, which is nice!)

The other scenario is just as dangerous for Yahoo. In scenario #2, Yahoo could be unable to sell brand advertising on their social media websites. As I’ve discussed before, advertisers like to buy brand media from properties that have, well, brand! And what is brand? It’s about trust, transparency, and consumers’ emotional connection with products and companies. For Yahoo to experience an oversupply of inventory there means that they aren’t effective in convincing advertisers to trust their properties enough to soak up all those ad impressions. This means that until these trust issues are resolved, it may be that the social websites they have will NEVER be monetizable at high CPMs (over $5), but instead must focus on sub-$1 stuff. Obviously, this is another huge worry for a company who is betting so much of their future on social web applications.

Ultimately though, this really should sound a LOUD warning for Web 2.0 entrepreneurs that are building social sites. Please keep in mind that:

- Do NOT assume you can attract eyeballs and the monetization strategy will just come together

- Do NOT assume that MySpace’s $900MM ad deal or YouTube’s $1.6B acquisition means there is strong underlying revenue

- And finally, do NOT assume that every pageview is equal, and that you can perform "chinese math" to calculate ad revenues

Ultimately, every startup out there must be very methodical in how they approach the overall market. Do you have a brand-oriented strategy, or a direct-response one? And once you pick, you have to align your personnel, resources, and product to capture dollars in each specific advertising market. If you ignore all of this, you will end up with a 1999 bubble company with eyeballs and no revenue – while this might work out for the defensive or disruptive acquisitions, you certainly will remove a lot of potential suitors of your company.

Development methodologies in video game design

From one of my favorite blogs: Persistent myths about Game Design.

As I’ve written earlier, I think the video game industry has a fresh and unique approach to product development that SOME high-tech companies could emulate. Specifically, video games are meant to solve an interesting problem – they are meant to systematically generate "fun" and "entertaining" experiences from users, which is difficult to design for. Because of this, the customers are central to every step of a game development process, rather than a theoretical afterthought. Having an abstract metric like "fun" forces them to constantly check with the user to make sure all their ducks are in a row. If their products were more "task oriented," my guess is that they wouldn’t emphasize the user so much, since completing tasks is much more concrete and traditional.

Because of that, you see game developers using rapid prototyping techniques, coupled with intense user-testing in order to prove out that their products are entertaining. Although web developers don’t face the same set of problems, I think there’s a lot we could borrow from the games industry, to see things from the users’ perspective rather than from a technology perspective.

Skill versus luck in entrepreneurism

Here’s an interesting paper published early this year: Skill vs. Luck in Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital.

This paper argues that a large component of success in entrepreneurship and venture capital can be attributed to skill. We show that entrepreneurs with a track record of success are more likely to succeed than first time entrepreneurs and those who have previously failed. Funding by more experienced venture capital firms enhances the chance of success, but only for entrepreneurs without a successful track record. Similarly, more experienced venture capitalists are able to identify and invest in first time entrepreneurs who are more likely to become serial entrepreneurs. Investments by venture capitalists in successful serial entrepreneurs generate higher returns for their venture capital investors. This finding provides further support for the role of skill in both entrepreneurship and venture capital.

An analysis and summary of the paper is available here. I just saved it to my desktop for future reading… maybe I’ll post a couple comments later on, if anything interesting pops out.

Yelp: An example of a high-value advertising model

I’ve been following Yelp in the news for quite a while now. In particular, their Alexa stats have been impressive to watch. As an aside, Alexa stats are really interesting to follow, particularly in the 1000 to 5000 range. That’s when sites reach a critical mass of typically more than a million pageviews per month – some internally modeling we’ve done at work shows that 4500 is about the magic number for 30 million pageviews/month. That’s the "up and coming" group of sites.

Anyway, Yelp will be very easy to monetize. In fact, in my opinion, it’s a textbook play for high-value direct response advertising. The reason is that, like search, review sites are only used when people are going through some sort of purchasing cycle. And sites like these (Zillow being another example) monetize very well because they are capturing this intent and can funnel leads to other websites in a manner that results in high conversion rates.

The main changes I’d make to the site – they need to focus more on organic search indexing. So all the URLs should list the titles of the reviews. That’s a huge part of the strategy, to make sure they get high ranked pages in all the search engines – if they don’t have people specifically to guide strategy around this, they are missing out. Then secondly, they need to figure out how to monetize these users in the backend. Throwing up text ads is probably one idea – they probably want to cut a special deal with Google to pass them specific context to finely target the ads – or they can hook into a pay-per-call company that charges these businesses by dynamically rewriting an 800 number that reroutes to the company.

Either way, it’s clear that Yelp is a company to watch – not only will they have the Web 2.0 hipness and audience to match, I predict they will have strong revenue traction. If they don’t turn out to be a multi-hundred million dollar acquisition or better, I’d be disappointed.

Cultural perspectives on failure and innovation

One of the more interesting lessons I’ve learned since joining the startup world has been the widely differing perspectives on failure and innovation. It’s a tremendous source of tension primarily built on a simple stylistic tension, which seems to occur in many different companies.

On one side, you have the free-wheeling Innovators, who instinctually move from one iteration of a project to another. Their goal is to throw up lots of ideas, see which ones stick, and build on those. Of course, this process continues indefinitely, piling failure upon failure to generate the successes. The attitude here is pretty much, "We don’t know what will succeed, so let’s do something simple, learn, and go from there." This is most commonly part of the Startup-Guy archetype, someone who is constantly on the move and shooting from the hip.

On the other side, you have the Analysis guys. Their goal is to make sure that everything’s buttoned up, that decisions are made for the right reasons, and that you have a repeatable process for success. Because most large companies have "cash cows" to protect and grow, these folks are very useful to scaling out a process in order to generate large-volume, low-risk, and high-margin products. They often have a systematic way of approaching issues, and rely more on logic and analysis than on instinct.

For me personally, I lean more towards the top (the no-holds barred Innovator) than the Analysis guy. There’s obviously lots of gray area, but I definitely tends towards one more than the other. Sometimes, when the going gets tough, I can bristle when interacting with Analysis folks. They can seem unimaginative and overly focused on process – but most importantly, their focus on making things repeatable (and big) may make something shitty into something shitty AND big. This may be what happens when you stick a bunch of these people on an unproven idea – rather than focus on verifying assumptions, testing hypotheses and coming up with new solutions, instead they want to focus on scaling up the unproven idea. Often, this leads to disasterous results. Grrr!

That said, I now realize that there’s a lot of gray area, and one is not mutually exclusive of the other.

For example, take the Big Pharma drug discovery process. The way it works is, you stick 100,000 (or whatever) possible drug candidates on one end of the "pipeline," and screen them out for all sorts of different things. Does it seem like it would work? Does it seem to attach to the right "targets?" Is it toxic to animals? Is it toxic to humans? Etc. Then at the very end, after 99,999 failures, 1 drug comes out that is approved by the FDA which makes a billion dollars a day. When rolled up, all the failure costs upwards of $800MM to produce one drug.