Author Archive

From analog dollars to digital pennies: The crisis in traditional media

How the core competencies of distribution-focused media companies are different than digital media websites

In this blog post, I’m going to discuss some random thoughts on about the evolution of media – I’ve recently been inspired by the conversations going on about the difficulties of transitioning from traditional media to the digital world. I thought I’d write down a couple notes on the media landscape and the idea that the skillsets of “pipes” companies – businesses that thrive on dominating distribution – are at a fundamental disadvantage relative to web businesses that promote interactive experiences.

Let’s get started with a rather famous person these days…

Miley Cyrus dominates because Disney dominates distribution (but for how long?)

For those that don’t follow the celebrity gossip blog as closely as I do, the girl above (who was born in 1992, which makes me feel old), is Miley Cyrus aka Hannah Montana. The Wikipedia article on her states:

Miley Ray Cyrus is an American child actress, singer, and songwriter. She is known for starring as Miley Stewart, “Hannah Montana” on the Disney Channel series Hannah Montana.

Cyrus became an overnight sensation after Hannah Montana debuted in March 2006.

Following the success of the show, in October 2006, a soundtrack CD was released in which she sang eight songs from the show. In December 2007, she was ranked #17 in the list of Forbes Top twenty earners under 25 with an annual earning of US$3.5 million.

What do Miley Cyrus, Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, Christina Aguilera, Shia LaBeouf, Hillary Duff, Keri Russell, and the cast of High School Musical have in common? I mean, other than having ridiculous “pop” careers? Well, they were all, at some point, part of the Disney marketing machine that takes in normal kids and spits out billion dollar franchises.

And when you want to understand how this marketing machine works, you have to look at how all-encompassing the Walt Disney Company really is – here are the companies that all fall under the Disney umbrella:

ABC, ABC Family, ABC Kids, Walt Disney Distribution, Walt Disney Motion Pictures Group, Disney Channel, ESPN, Jetix, Walt Disney Studios, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, Walt Disney Television Animation, Walt Disney Records, Walt Disney Pictures, Touchstone Pictures, Miramax Films, ABC Studios, Playhouse Disney, Disney Consumer Products, Pixar, Soapnet, Disney Interactive Studios, Muppets Holding Company, Disney Store, Toon Disney, New Horizon Interactive, Hollywood Records

And with 137,000 employees and >$35B in yearly revenue – well, if you want to make a little girl like Miley Cyrus famous, turns out you can!

Media consolidation and vertical integration go hand in hand

The point is, Disney and the many companies that would be considered its peers (Viacom, Fox, Sony, Vivendi, and the like) own the entire value chain from start to end in traditional media. In the “content is king” model, the focus is on producing content, but then owning the marketing, the distribution, and everything in between.

Does it surprise you that Time Warner both makes movies, and publications that promote movies, as well as a cable company that can distribute them on-demand? Or that one of the driving forces for Rupert Murdoch to buy MySpace was to use it to promote its movies, as discussed in this informative article in Hollywood Reporter? The saying, “content is king” means that when you’re the only game in town, you’re able to use your considerable cross-channel leverage to boost whatever you want and make it popular.

The problem is, where does that leave the customer?

If media companies are ultimately “pipes” companies – ones that primarily focus on distribution – what is their incentive to serve the consumer? I think that in the tech world, when we’ve seen this happen with Microsoft when it achieved superior distribution leverage relative to all its competitors. It creates perverse incentives to to try to squeeze whatever you can out of consumers, rather than innovating new products to serve them. And I’d argue that a lot of what we see in the entertainment industry – endless sequels, manufactured pop bands, child-actor-to-paparazzi-bait actresses – are all indicators that this is already happening. Why take content risk when you can just out-distribute and out-promote whatever you want?

Is the Mummy 3 the entertainment equivalent of Windows Vista? (I guess I shouldn’t be too harsh, after all the movie hasn’t released and I haven’t seen it yet – maybe it will be good!)

How vertical integration weakens with the internet

Of course, this vertical integration strategy starts to fall apart when you’re talking about digital content on the internet. The reason is that it’s hard to dominate it in the way that you can dominate offline distribution. It’s hard to be the only game in town. When the game is to own cable wiring, satellites, movie theaters, radio towers, and all that jazz, then the big guys have a natural advantage – scale is rewarded, and the bigger you are, the easier it is to own a bunch of infrastructure and operate it efficiently.

But on the internet:

- Anyone can set up a website

- It’s easy to copy, pirate, and otherwise separate your content from your distribution mechanisms

- With the advent of UGC, the engagement around media is also being captured off branded media sites as well

- Passionate vertical web communities are more engaged and can serve their specific audience better

- … and any entrepreneur with a couple hundred grand might end up with a website bigger than anything the old-school media companies can put together

So if you assume, at runrate, that any media you release will quickly (and virally) spread itself across the world, with or without your approval, and that people are likely to watch it at destinations you don’t own, then the traditional model starts to break. Things that you don’t expect to take off suddenly do, and the well-orchestrated launch of a “official” website for content might fall flat on its face. The problem is that the traditional source of power for media companies, the vertically integrated apparatus of content, marketing, and distribution becomes broken up into little pieces on the internet.

To this, I make the observation:

With the distribution efficiency of the internet, it becomes harder to control your consumers, and that’s a good thing :-)

So let’s talk about what companies might succeed in this new world…

The core competencies needed to succeed in digital media

If content becomes increasingly commoditized, and fragmented among many distribution vehicles, then what happens next? I’d argue that the new skills required to succeed in this era are NOT:

- Understanding how to best own/operate pipes, like cable systems, satellites, radio towers, etc

- Strong-arming partners and distribution to lock content into place

- Finding media synergies to cross-promote content and “make” hits

Instead, I’d argue that the new skillsets will be around serving the consumer, not pushing them. This means that media companies will need to grok:

- The economics of syndication and monetizing content off of “branded” media destinations

- Search, browse, and other aggregations of media content

- Personalization, recommendation, and social filtering

Will the traditional media companies make the leap? Or will they retreat into content, letting new players own the distribution layer? That seems to be what’s happening with YouTube, iTunes, and other strong players in the digital distribution world. The jump from controlling consumers versus serving them may be too big for these companies to make, but only time will tell.

Suggestions and comments welcome!

What are you really trying to measure?

I hugely enjoyed Fred Wilson’s blog this morning, where he discussed Three Statistics That Lie. In particular, he singles out:

– RSS subscriber numbers

– Facebook app install numbers

– Follower numbers on Twitter, Friendfeed, Tumblr, or some other social media service.

He points out the fact that RSS numbers show subscribers, but this number never goes down even though some people never actually read your blog – they just subscribed eons ago. Same with Facebook apps, and Twitter followers.

The point is, what are you really trying to measure?

In the Facebook case, the reason why “installs” feels like it’s not a great metric is that ultimately, value is generated by revenue, which is generated by ad impressions and CPMs, which are ultimately generated by active users. And active users obviously correlate with total installs, but it’s not a great correlation depending on how old the app is.

I would even break those active users down to users you can expect to retain, versus people you’re just dumping in and don’t expect to see again. (For example, RockYou’s Super Wall app recently had its viral channels taken away, and it showed that only 30% of the users were “retained” users versus people who come back because of notifications and such)

Anyway, numbers are numbers and they are meaningless if they’re measuring the wrong thing. So start with the business questions, which likely revolve around value generated as defined by an engaged audience that comes back and the revenue they throw off, and begin your model from there.

Trying out the new Amazon Recommendations widget

I recently read about Amazon’s new recommendation widget and I’d try it out. I think it’s another neat example of why even though Amazon’s business is almost all retail, they are really more of a technology company at heart.

In general I’ve found that the Google ads on my site absolutely don’t monetize at all – no surprise there :) Let’s see how these do.

Obama and McCain: How political marketing has evolved from offline to online

What?? A political post?

I’ve never blogged about politics before, and I’m not going to start :) This post is 100% about the evolution of marketing in the world of politics, not about any political positions. Anyway, I’m compelled by the fact that I’ve been encountering article after article about Obama’s mastery of the internet, and before that Howard Dean’s.

In particular, there was a great article in The Atlantic Monthly called The Amazing Money Machine with the subtitle “How Silicon Valley made Barack Obama this year’s hottest start-up.” In it, there are some great passages on how the Obama campaign has used technology to their advantage:

To understand how Obama’s war chest has grown so rapidly, it helps

to think of his Web site as an extension of the social-networking boom

that has consumed Silicon Valley over the past few years. The purpose

of social networking is to connect friends and share information, its

animating idea being that people will do this more readily and

comfortably when the information comes to them from a friend rather

than from a newspaper or expert or similarly distant authority they

don’t know and trust. The success of social-networking sites like

Facebook and MySpace and, later, professional networking sites like

LinkedIn all but ensured that someday the concept would find its way

into campaigning. A precursor, Meetup.com, helped supporters of Howard

Dean organize gatherings during the last Democratic primary season, but

compared with today’s sites, it was a blunt instrument.

And of course, you can’t forget Obama Girl, who now has 8.8 million views, or the Obama Facebook group which has over a million supporters now. Overall, pretty amazing stuff.

But as I mentioned above, this isn’t the first time that the Internet played a role in politics, since the Howard Dean supporters aggressively used services like Meetup and the MoveOn website to organize their efforts. Here’s an article from Wired magazine in 2004 describing the Howard Dean run.

Republicans and their direct mail expertise

Of course, back in 2004, another big story that played was the mastery the Republicans showed of direct marketing, particularly by Karl Rove who previously spent many years in that industry. In another article from The Atlantic, called Karl Rove in a Corner, there are some choice passages on how he thinks about targeting and direct marketing:

When Rove arrived in Alabama, in 1994, his clients were initially

puzzled as to why he was having them campaign in rural and less

populated parts of the state rather than the urban areas they were

accustomed to. It turned out that he had run an electoral regression

analysis on each of the state’s sixty-seven counties, and for

efficiency’s sake he put his four judicial candidates together on a bus

trip to the counties with the highest percentage of ticket-splitters.

“Karl got us focused on the fact that it was a matter of convincing

Democratic voters who were already conservative to vote for Republican

candidates,” Mark Montiel, a candidate on the trip, explains, “because

that was who best expressed their views.”… snip …

As with direct mail, Rove was skilled at reaching specific voter segments with television commercials, buying air time only during programs that he believed would attract the audience he was trying to reach. In his Alabama races he was known particularly to withhold advertising from The Oprah Winfrey Show and similar afternoon programming—”trimming a media buy,” as it is known in the trade. Bill Smith, who worked on a series of close races with Rove in Alabama, says, “There’s a real overlap in what he specialized in professionally and what you need to do in a tight race.” Whether he is seeking donors in a direct-mail fundraising campaign or manipulating a particular demographic sliver to win a close race, Rove’s professional goal has been strikingly consistent: to reach the right people.

There’s also another great article on the attempts for Mitt Romney, a Harvard Business School grad, to do this for his (ultimately failed) presidential campaign in the Post covered here. The point is, they were very smart about the process of collecting a vast database of data, using advanced marketing techniques like cluster analysis, machine-learning segmentation, regression analysis, etc. This is good stuff!

That said, in almost every article I’ve read about the subject, the focus of the Republicans seems emphasize direct mail – perhaps that’s a better vehicle for their demographic, or perhaps because that’s just the skillset they have developed over the last 10 years. However, there’s many studies about the efficiency of internet advertising versus offline, and politics is no exception – let’s take a deeper look at this:

Comparing direct mail to internet

There’s some interesting numbers comparing direct mail and internet-based donations in an article from the American Enterprise Institute, which states:

It is not just that he has built this

veritable army of contributors, most of whom will follow with him

through the fall campaign and beyond, if he is able to win the White

House. Having this base of small donors through a process that is

incredibly inexpensive to run, with fundraising costs that are 5 to 10

cents on the dollar (compared with 95 cents for direct mail), frees

Obama from the punishing, time-consuming burden of attending scores of

fundraisers and making thousands of phone calls to potential donors.

(Of course, Obama is not at the same time ignoring the $2,300 donors

and bundlers, which may create more flak for him through the rest of

the campaign. But he will certainly spend much less of his own time

courting donors than will McCain.)

(I bolded the sentence above). Wow! 5-10 cents on the dollar versus 95 cents for direct mail – what an amazing statistic. If you believe that, then it means you are almost 20X more efficient with internet marketing than direct mail, which is a huge number.

I’m not following the political campaigns that closely, but I’d be interested in a couple broad questions about how the approaches of the two parties are shaking out, from a macro-perspective:

- First off, are the Republicans majorly lagging in their ability to use the internet as a political vehicle?

- Similarly, do marketing channels like broadcast media and direct mail – which are “push” – fundamentally different than interactive media, like Facebook apps, YouTube UGC, etc.

- Can the same techniques that Rove used back in 2004 be re-applied to the internet? Is the DNA there, and it’s just a matter of time before the GOP cracks the nut for online marketing as well?

- For online marketing in politics, how quantitative are the approaches right now? Or is the offline-to-online opportunity so ripe that the qualitative stuff works without much thought?

Anyway, if anyone has any opinions or insight onto this, I’d be very interested to know. Comments and suggestions always welcome!

25 reasons users STOP using your product: An analysis of customer lifecycle

Churn from a customer lifecycle perspective

As much as I blog about viral marketing, it can’t be avoided that having healthy product retention is an equally (and incredibly) important part about having a successful product. Thus, in addition to talking about the issues around user acquisition, a similar discussion must be had around user churn.

In the customer lifecycle perspective, you look at the product from the perspective of a user that has a series of experiences starting from newbie and going into an advanced role. In addition to looking at the success cases, looking at the failure cases is informative too – you want to analyze your product for potential exit points and relate them to both quantitative and qualitative measures. More on the customer lifecycle concept here, by Josh Kopelman at First Round Capital.

Anyway, here’s a good example of this from the games industry: At the Austin Game Developers conference last year, there was a great presentation on why players leave their MMOGs from Damion Schubert (who also writes a mean blog here). There’s a very convenient writeup of his talk at Massively, which includes a great list. I’d encourage reading it in full. Obviously, the challenges that face more web-like products are very different, yet the same approach can be used.

Customer lifecycle within a social product

I imagine that many in the readership are working on social products – for any product in this space, you often have a number of fuzzy stages that a user can move through during their lifecycle. This may include stages like:

- First experience

- Soloing and single user value

- Encountering some friends(?)

- Hitting critical mass for social

- Becoming a site elder

Obviously every product is different, but the rough idea should hold for every social product out there. Early on, the initial experience is all about whether or not the user sees value in the product, and whether or not it “looks okay.” Then, oftentimes the users won’t have enough friends to make the site useful, in which case they fall back on a solo experience. Once they start hitting some other folks on the site, and making friends, then if done correctly, the site will hit critical mass and things will be sticky. And finally, in some products, some % of these users will turn into mods or admins or otherwise be elders within the product.

25 exit points

Now let’s look at all the different reasons why people might leave at any point – and obviously, the retention gets stickier and stickier in each stage, so perhaps reasons like “the site is too addictive!” become less effective :)

Anyway, there they are:

- First experience

- “I don’t get what this site is about”

- “This site is not for people like me”

- “The colors/design/icons look weird”

- “I already use X for that”

- “I don’t want to register”

- Soloing and single user value

- “I don’t have time to get involved in a site like this”

- “I’m lonely, not enough happens”

- “I forgot my password”

- “I don’t know how to talk or meet people”

- “I’ll just check on this account every couple months in case something happens”

- Encountering some friends(?)

- “People on this site are mean”

- “People I don’t know keep messaging me, WTF?”

- “I want my friends to use this, but none of them are sticking”

- “I’m getting too much mail from this site”

- “I only have 3 friends, this site is still boring”

- Hitting critical mass for social

- “This site takes up too much of my time”

- “Too many people are friending me that I only sorta know”

- “People are stalking me based on my pics and events!”

- “This Top Friends thing causes too much drama”

- “I’m getting flooded by e-mails for everything that anybody does”

- Becoming a site elder

- “The guys who run this site aren’t building feature X that we really need!”

- “The guys who run this site build feature Y that’s going to destroy this site!”

- “I’m doing a lot of work but I’m not getting anything for it”

- “I’m bored because there’s nothing left to do”

- “Newbies are fun to pick on :)” (wait, maybe that’s a benefit!)

Obviously, this is just a quick brainstorm of a list, but the point is, the reasons why people churn is often very different depending on their lifecycle. And some of the best things you can do for your product, in terms of retention, are things that are very positive for newbies, but might have side-effects elsewhere. You always want to balance each of these things off, depending on your product and business goals.

Am I missing anything else obvious? Comments and suggestions are always welcome!

Companies reading Futuristic Play – advertising, games, media, and more

One of the more unfortunate things about writing a blog focused on long-form essays that are not easily discussable is that you don’t get a ton of information about your audience just from comments and e-mail dialog. Through limited methods, I have some very rough visibility from what I can put together based on referrer logs, subscribed email addresses, and other sources.

Anyway, here’s a meta-blog post, in tradition with previous ones on top referrers, subscriber boosts from Scoble, and others, I wanted to share a short collection of the wonderful audience I’m very grateful to have reading this blog.

It’s pretty amazing to see how wide and interdisciplinary the audience is – there’s a ton of folks from super-consumery publishers/games, but also advertising and finance folks.

Here’s a selection of the companies that caught my eye:

Advertising and B2B:

- Aster Data Systems

- Medio Systems

- Revenue Science

- Tacoda

- Right Media

- Publicis Groupe

- … and a bunch of ad networks

Games and entertainment

- Electronic Arts

- Linden Lab

- NCSoft

- Sulake

- … and numerous startups like IMVU, Gaia, AreaE, and Weeworld

Media

- Joost

- Yahoo

- Virgin

- Slide

- MTV

- Hi5

- Tagged

- … and tons of Facebook developers and apps

Finance

- Lazard Freres

- Elevation Partners

- Mohr Davidow Ventures

- Blue Run Ventures

- Sierra Ventures

- Bessemer Venture Partners

Sorry if I’m missing anyone – I have a lot of empty referrer URLs, personal gmail/hotmail/yahoo addresses, and many other untraceable sources :)

Anyway, thanks to everyone for reading!

Poll: How do you launch a new product or service?

(If you’re viewing this in an RSS reader, you have to view the actual blog to see the poll below)

Craigslist to surpass eBay in 2009? Compete and Quantcast seem to think so…

At the Structure '08 conference, one of the eBay guys made the comment that scalability was a solved problem for them. A fellow conference goer observed:

airplanedan: must be nice to be ebay… James Barrese says they have scaling figured out and never have to worry about it again #structure08

This comment made me curious… Growth obviously makes scalability really hard, and how much is eBay growing anyway?? After pulling up a couple charges, in particular comparing things to Craigslist, you see some interesting results.

According to Compete, Craigslist has grown 76% in the last year while eBay has declined 11.6%:

If that pace continues – and your high schools stats warned you about the dangers of extrapolating- then Craigslist will pass eBay within the year. Wow! That would be big.

That means Craigslist will not only be the bane of all the old media newspapers, but also a former dotcom darling.

Here's the Quantcast graph for another datapoint:

More detailed analysis of social network value on Techcrunch

Michael Arrington posted an article this morning called Modeling the Real Market Value of Social Networks that uses a similar approach more data (and a better granularity of data) than the blog I wrote last week on the same topic. It's absolutely worth reading, so check it out.

(And Mike, thanks for the shoutout in the article!)

His blog concludes with the following chart, detailing valuations:

As you can see, MySpace, Facebook, Bebo, and Hi5 are all in the top 4, but interestingly enough, you also have companies like Ameblo.jp, Buzznet, Skyrock, Mixi.jp, and a bunch of other companies that have not quite entered the Web 2.0 discussion. Obviously it's looking at data like this which prompts those kinds of questions. In particular, thinking about the role of international traffic in social networks drives awareness of the fact it's harder to monetize.

After all, a pageview is not just a pageview – you have to think about where it's coming from, where it's being displayed, when it's being displayed relative to the user's session, who it's being sold by, and a myriad of other constraints that determines advertising CPMs.

MySpace versus Facebook: Analysis of both traffic and ad revenue, using Google Trends

(above, Facebook beating MySpace in Australia with the crossover at Oct 07)

Social networks have weaker network effects than previously speculated

- First off, MySpace is staying dominant in a few countries, like the US, Germany, Italy, Japan, etc

- Across the board, MySpace is the incumbent, and Facebook is coming from behind

- However, Facebook beaten MySpace on traffic in 14 countries over the last year

- In particular, June ’07 to Oct ’07 was particularly rough for MySpace, where 10 of the 14 countries were passed in this period

- In the markets where MySpace leads, you may consider them “mature” markets in the sense that both services have plateau’d in traffic – it’s not like MySpace growth is outpacing Facebook’s

Here’s the full table of data, so you don’t have to do the work:

| country | myspace leads | facebook leads | crossover date |

| Australia | X | Oct-07 | |

| Austria | X | ||

| Belgium | X | Nov-07 | |

| Brazil | X | ||

| Canada | X | ||

| China | X | May-07 | |

| Denmark | X | Oct-07 | |

| Finland | X | Sep-07 | |

| France | X | Nov-07 | |

| Germany | X | ||

| Hong Kong SAR China | X | ||

| India | X | ||

| Italy | X | ||

| Japan | X | ||

| Netherlands | X | Mar-08 | |

| Norway | X | ||

| Portugal | X | ||

| Singapore | X | Jun-07 | |

| South Korea | X | Sep-07 | |

| Spain | X | May-08 | |

| Sweden | X | Jul-07 | |

| Switzerland | X | Oct-07 | |

| Taiwan | X | Apr-07 | |

| United Kingdom | X | Jun-07 | |

| United States | X |

Overlaying advertising markets

Now, the second question is, how do advertising markets play into this? After all, it’s not enough to win on traffic, but you want to win on valuable traffic. For this discussion, I’ll borrow a diagram Jeremy Liew from Lightspeed wrote about regarding ad spend both domestically versus internationally, in 2007:

Here, you see that the US is by far the largest ad market, and is worth more than the rest of the world combined. I think that’s a key observation. Another observation can be made by combining this diagram with the traffic table above:

| country | myspace | crossover | 2007 ad spend (MM) | |

| United States | X | 19500 | ||

| United Kingdom | X | Jun-07 | 4727 | |

| Japan | X | 3397 | ||

| France | X | Nov-07 | 2548 | |

| China | X | May-07 | 1269 | |

| Germany | X | 1142 | ||

| Canada | X | 950 | ||

| South Korea | X | Sep-07 | 779 | |

| Brazil | X | 400 | ||

| India | X | 86 |

- MySpace leads in the major market (the US) but is losing ground overseas

- The overseas losses are material losses – not just random non-revenue countries

- The major losses all occurred in the mid/late 2007 timeframe

- Several markets are plateauing in traffic, meaning that the social network market is starting to mature – consider that MySpace+Facebook uniques, duplicated, is over 90M active users, which is a huge percentage of the online audience in the US

- How strong are the network effects of social sites, if incumbents can be displaced? Maybe it’s not so strong after all

Comments or suggestions welcome!

Free consulting on retention metrics* :)

*in exchange for data

Looking for usage/retention data

I am looking for some usage/retention data to analyze using some tools I've built in the last couple weeks. In particular, I'm interested in better understanding retention rates and segmentation analysis for web products. Unfortunately, I myself do not have a lot of this kind of data at this point, and would like to work on it.

So, I'm offering some consulting services around this for free, in exchange for a complete dataset that I'm hoping some of my readers may have. I won't guarantee anything, but I'll share whatever I come up with, and keep it completely confidential.

Data specs

This is the kind of information you'd need:

- list of user IDs and when the users were created

- list of user sessions with timestamps, or list of all user events with timestamps (which we can use to approximate sessions), or list of when each user uninstalled an app, etc.

- that's it!

If you're interested, shoot me an email at voodoo [at] gmail.

Thanks!

Andrew

Are you working on a product targeted at teens? 10% off YPulse Conference on July 14-15

Thinking about Generation Y, not just tech

One of my favorite blogs, YPulse, covers a great range of marketing, tech, and lifestyle issues around the teen demographic. The reason why I'm a fan is because they aren't just tech focused, but consider the research from A-Z on this demographic. Obviously it's great for people who are:

- Working on social gaming or virtual worlds

- Building out social networking sites based around games, media, or otherwise

- Similarly, anyone who's doing Facebook or OpenSocial apps, to figure out what makes this demographic tick

Anyway, they are having a conference on July 14-15 in San Francisco, and they let me share a discount code. Here's the registration info:

REGISTER HERE

10% discount code: FUTURISTIC1

You can view the agenda here. They are having a screening of a documentary covering the demographic as well as a Q&A with a panel of teenagers at the end of the night also, which should be fun.

Sessions

A couple sessions I'm interested in – see you guys there:

Brand Engagement in Virtual Worlds for Youth

* Creating virtual world experiences residents will love

* How do you measure ROI in virtual worlds?

* Connecting virtual engagement with real world engagement

Panelists:

Lauren Bigelow, General Manager, WeeWorld

Teemu Huuhtanen, President, North America, Sulake (Habbo)

Craig Sherman, CEO, GaiaOnline

Michael Wilson, CEO, There.com

Are Girls The New Geeks?

* Understanding how girls and boys use the web

* What works in reaching girls vs. boys

* Girls are creating content, but what are they learning?

Panelists:

Nancy Gruver, Publisher, New Moon Girl Media

Allison Keiley, Online Content and Community Manager, Girls, Inc.

Ashley Qualls, CEO, WhateverLife

Holly Rotman, Senior Web Editor, eCRUSH/eSPIN; Writer, "Advice Girl" column, eCRUSH.com, Hearst Magazines

Where are all the video startups? Maybe Content=King, online and offline

I ran across this interesting diagram from comScore on the top video properties online:

|

Top U.S. Online Video Properties* by Unique Viewers |

||

|

Property |

Unique Viewers (000) |

Average Videos per Viewer |

|

Total Internet |

134,471 |

81.6 |

|

Google Sites |

83,720 |

49.7 |

|

Fox Interactive Media |

52,046 |

10.7 |

|

Yahoo! Sites |

37,323 |

9.4 |

|

Microsoft Sites |

29,908 |

9.0 |

|

Time Warner – Excl. AOL |

20,627 |

6.7 |

|

Viacom Digital |

19,367 |

10.3 |

|

AOL LLC |

19,115 |

5.0 |

|

Disney Online |

10,805 |

9.1 |

|

ESPN |

9,026 |

9.2 |

|

CBS Corporation |

7,993 |

7.1 |

My first thought was… why are there no startups on this list? YouTube is the closest, and obviously they are dominating, but how about all the other folks?

A theory on this is that most startups have focused on aggregating long-tail video online, and displaying it as a "content site" similar to YouTube. That is, one would focus on just aggregating and displaying content, rather than building too much complexity on top of it.

Compare this strategy to the one employed by many of the top media companies listed above – they are taking their wells of proprietary content and posting it online, and mainstream content is able to drive traffic with or without surrounding featureset. If you check out ABC.com or many of the major network sites, they don't do anything fancy – just post the content in Flash and off you go. It really makes you believe that content is king, both online and offline.

Social gaming design – Bartle types versus Web 2.0 participation pyramid

By spending time in the “social gaming” space, it’s interesting to see the intersection of approaches from both the consumer internet folks versus the traditional game folks. In addition to business models (ads versus subs/virtual goods) or product emphasis (functionality versus storytelling/characters/etc) or other topics, I’m particularly fascinated by the difference in how they think about their players/users and their activities.

Let’s look at the two approaches – both the “Web 2.0” view as well as the games perspective. The former is represented by a pyramid, and the other is a 2-axis landscape.

A while back, Bradley Horowitz (then at Yahoo) wrote an article on a “pyramid of value creation” classifying Creators, Synthesizers, and Consumers. He uses the following diagram and writes – bold formatting is mine:

The levels in the pyramid represent phases of value creation. As an example take Yahoo! Groups.

- 1% of the user population might start a group (or a thread within a group)

- 10% of the user population might participate actively, and actually author content whether starting a thread or responding to a thread-in-progress

- 100% of the user population benefits from the activities of the above groups (lurkers)

There are a couple of interesting points worth noting. The first is that we don’t need to convert 100% of the audience into “active” participants to have a thriving product that benefits tens of millions of users. In fact, there are many reasons why you wouldn’t want to do this. The hurdles that users cross as they transition from lurkers to synthesizers to creators are also filters that can eliminate noise from signal. Another point is that the levels of the pyramid are containing – the creators are also consumers.

The use of a pyramid reinforces some subtleties which I bold above:

- There’s a hierarchical view of how users are perceived, with a linear path

- Creators are generally seen as “higher value” than the less involved users

- There’s an effort to “convert” lower value users into creators

Another good discussion and example of the pyramid point of view is here at Jeremiah Owyang, in an article called See Actual % of “Community Pyramids” with Technographic Data.

Let’s return to the pyramid a bit later in this blog.

The Games point of view

The four things that people typically enjoyed personally about MUDs

were:i) Achievement within the game context.

Players give themselves game-related goals, and vigorously set out to achieve them. This usually means accumulating and disposing of large quantities of high-value treasure, or cutting a swathe through hordes of mobiles (ie. monsters built in to the virtual world).ii) Exploration of the game.

Players try to find out as much as they can about the virtual world. Although initially this means mapping its topology (ie. exploring the MUD’s breadth), later it advances to experimentation with its physics (ie. exploring the MUD’s depth).iii) Socialising with others.

Players use the game’s communicative facilities, and apply the role-playing that these engender, as a context in which to converse (and otherwise interact) with their fellow players.iv) Imposition upon others.

Players use the tools provided by the game to cause distress to (or, in rare circumstances, to help) other players. Where permitted, this usually involves acquiring some weapon and applying it enthusiastically to the persona of another player in the game world.

Later on in the article, he also touches on the dynamics between each one of these Bartle types, and how they interact to create the community that makes up a game. He also discusses methods of increasing or decreasing the prevalence of certain types, since oftentimes having too many or too little of a particular type can cause imbalance to the community.

A couple observations on this:

- The 4 types are primarily treated as peers to each other

- By presenting it as a 2×2 landscape, it also expresses the idea that a player might be in one type yet flirt with another

- Yet, the diagonals are problematic, since it’s hard to express an Achiever who is also a Socializer

Let’s compare the two viewpoints now.

Comparing the two perspectives

It’s clear that there are clear differences between the two views. While one more closely resembles a linear, hierarchical view, the other represents a flatter, multi-variable view.

In general, I think the two views are in conflict with each other due to the emphasis on user-generated content versus company-created content. In a pure UGC web 2.0 site, you need the content creators otherwise there’s nothing to do for anyone else. Take a site like Digg or Facebook, and if it’s just you on the site, it’s not so interesting. Compare this perspective to the games world, which has long built gradual “solo” experiences that then open into social experiences.

In almost any MMO, you can still play it for a while before you have to start thinking about other people. There’s a long “single user” experience that makes the game fun and entertaining, even if you’re the only person logged on. For socializers, you can talk to NPCs and get your kicks that way. For achievers, you can fight monsters and level up your character. For explorers, you can still check out the world and try out all sorts of different things. By investing in a content experience up-front, there’s less of a reliance on content creators to make it all work.

In general, comparisons like this make me think more about the user/player lifecycle of any product – how do you bootstrap the initial experience and make that fun? How do you pivot the user into trying other things, in particular with real live people? How do you build the critical mass to make social experiences interesting? As always, there’s a lot for Web folks (like me) to learn about from the games people.

Comments and suggestions always welcome!

Social Gaming Summit: Recap and observations

For every conference event summary that's posted, there's already an existing one that's earlier, more comprehensive, and better written ;-)

In this case, Justin Smith and Mashable have already posted some partial writeups here and here. Instead, I'll just focus on a couple observations shared during the panel discussions which I found interesting.

A very compelling point made today by the IMVU CEO Cary Rosenzweig was around the process of designing IMVU from the ground up, rather than their previous project There.com. He said that when the IMVU originally constructed There.com, the problem was that they created a ton of "space" without the social activity to make it dense enough and interesting enough. It was too easy for users to end up wandering around the environment without interacting with each other enough. This description reminded me of the problems that Half Life faced early on, described here, where the levels weren't fun and had to be reconstituted to be as "dense" experientially as possible, to make it interesting.

Another comment I liked was when Daniel James from Three Rings pointed out that in many cases, virtual worlds can be much tougher to build than traditional "games." The reason is that for his previous game, Puzzle Pirates, which revolves around a pirate theme, there is clear context. You know that pirates seek treasure, fight other pirates (and the British Navy), steer ships, say "ahoy" and "AARRR," and other ideas that fit into the mythology. This ultimately creates an internal set of motivations where the players sorta know what to do!

Social Gaming Summit tomorrow – see you guys there!

Charles Hudson of Gaia invited me to attend the Social Gaming Summit tomorrow in San Francisco. Should be a lot of fun! I'll write a quick blog covering the conference, to sum it all up.

10:00am – What Makes Games Fun?

We all like to have fun, right? What is it about games that makes them so fun? Is it gameplay? Social interaction? Achievements and accomplishments? Our panel of thought leaders will share their perspectives on what it takes to build a fun game and why building fun into games is more difficult than it looks.

» Erik Bethke – CEO, GoPets

» Dr. Ian Bogost – Founding Partner, Persuasive Games

» Nicole Lazzaro – President, XEODesign, Inc.

» John Welch – Co-Founder, President & CEO, PlayFirst

» Jeremy Liew – Managing Director, Lightspeed Venture Partners (moderator)

11:00am – Casual MMOs and Immersive Worlds

Many so-called “casual MMOs” and immersive worlds are casual only in the sense that the point of the game is not to bash gruesome looking monsters or the game isn’t set in a sci-fi fantasy world. The engagement story around existing and upcoming casual MMOs is real and very compelling. This panel will discuss what it takes to build a successful casual MMO that users love to play.

» Min Kim – Vice President of Marketing, Nexon America

» Patrick Ford, VP Marketing and Community Development, K2 Networks

» Kyra Reppen – SVP and GM, NeoPets

» Craig Sherman – CEO, Gaia Online

» Joey Seiler – Editor, Virtual Worlds News (moderator)

1:30pm – Asynchronous Games on Social Networks

There are a lot of interesting asynchronous activities happening on social networks. Some of them are traditional games, others are games in disguise. Join us and hear from some of the leading voices in this space share their views on how to build great gameplay characteristics into social networking applications and what opportunities exist for gameplay to take advantage of the social graph.

» Siqi Chen – Founder, Serious Business (Friends for Sale)

» Blake Commagere – Founder and VP Engineering, Mogad

» Shervin Pishevar – CEO, Social Gaming Network

» Mike Sego – Developer, (fluff)Friends

» Andrew Chung – Principal, Lightspeed Venture Partners (moderator)

2:30pm – User Generated Games in Social Networks and Virtual Worlds

Games are one of the most popular activities on social networks and virtual worlds. Increasingly, users are taking it upon themselves to create games and entertainment of their own within the context of existing online environments. Curious as to what’s driving this behavior? This is the panel for you.

» Daniel James – CEO, Three Rings

» Jeremy Monroe – Director of Business Development, Sports & Entertainment, North America, Sulake Inc.

» Ted Rheingold – Founder, Dogster and Catster

» Cary Rosenzweig – President and CEO, IMVU

» Dean Takahashi – Writer, Venture Beat (moderator)

4:00pm – Building Communities and Social Interaction In and Around Games

Social networking and games go hand in hand. Whether it’s taking advantage of the relationship data in social networks to build novel gameplay or building community among people who play games, game developers are discovering clever ways to build real communities around the games they’re developing. Hear from our panel of thought leaders about what it takes to successfully integrate community and social interaction into the next generation of games.

» Jim Greer – CEO, Kongregate

» Amy Jo Kim – CEO, Shufflebrain

» Mark Pincus – Founder and CEO, Zynga Game Network

» Dave Williams – SVP, Shockwave, AddictingGames

» Brandon Sheffield – Gamasutra (moderator)

5:00pm – Monetization and Business Models for Social Games

There are a handful of viable (proven) business models for social games. How should game developers go about choosing the best business model for their games? Our panel of experts will share their thoughts on the various business models and how to think through the right one for a given game.

» Jameson Hsu – Co-Founder and CEO, Mochi Media

» Matt Mihaly – CEO and Creative Director, Sparkplay Media

» Mattias Miksche – CEO, Stardoll

» David Perry – CCO, Acclaim

» Ravi Mhatre – Managing Director, Lightspeed Venture Partners (moderator)

Dear readers, need a quick favor!

Hi all, I'm looking for recommendations/intros to find a great frontend engineer for a consumer internet project I'm working on. Ideally, would be located in the Bay Area or willing to relocate.

5 steps towards building a metrics-driven business

Don't ask me about viral marketing, ask me about metrics

Given my history blogging about viral marketing, I'm occasionally approached by folks who ask me, "For product X, how would you promote it and make it viral?" I think there's an expectation that there's a playbook which you can directly apply to every situation.

- A/B testing your upload page to make people more likely to upload

- Delivering a ton of email notifications prompting users to upload

- Using switch-and-bait tactics like information-hiding, creating false incentives, etc.

- Creating a gimmicky points system to upload photos

In many cases, I feel like many Facebook apps are trying to solve their problems by enacting the solutions as above. I think the quantitative side lends itself well to the above approaches, yet you rapidly hit diminishing returns.

- Repositioning the product for a higher resonating value proposition

- Going after a different kind of audience to target their needs

- Recalibrating the "core mechanic" of the product to make uploading photos a natural part of using the product (like HotOrNot, for example)

Finally, it's important to execute your scientific approach with proper test and control methods:

A/B testing is a method of advertising testing by which a baseline control sample is compared to a variety of single-variable test samples. A classic direct mail tactic, this method has been recently adopted within the interactive space to test tactics such as banner ads, emails and landing pages.

Employers of this A/B testing method will distribute multiple samples of a test, including the control, to see which single variable is most effective in increasing a response rate or other desired outcome. The test, in order to be effective, must reach an audience of statistical significance.

This method is different than multivariate testing which applies statistical modeling which allows a tester to try multiple variables within the samples distributed. (from Wikipedia)

Summary

- Create clear, measurable goals

- Make an uber-model that breaks down key variables

- Collect both quantitative and qualitative data

- Generate hypotheses around key variables and variable combinations

- Execute test and control methods, and don't confuse correlation with causality!

For those who are dipping their toes in the water, I hope this helps!

Users, customers, or audience – what do you call the people that visit your site?

5 second personality test

This is a just-for-fun post on the way that language changes our perspective on design. I've been thinking a lot about these nuances in the way that it creates hidden assumptions on business models, how we treat our partners, our users/customers/audience, and other folks in the industry. As a result, I've come up with a one question personality test ;) Here's the question below:

What do you call the people who are on your site?

- Users

- Customers

- Audience

Have your answer?

Read below for some quick thoughts on what your answer could mean.

Audience

Folks that use the word "audience" are likely to have an advertising and monetization perspective. Ultimately, companies with an ad perspective see the audience they are building into an asset to be sold to their "real" customers, the advertisers. And so I hear phrases like X wants to "target this audience" or that they're "aggregating the Y audience" or similar wordings.

As I wrote in Your Web 2.0 startup is actually a B2B in disguise, the process of generating all those millions of pageviews is just step #1, and step #2 is to actually sell them to the advertisers who want to target this audience. That's absolutely a valid perspective.

Customers

The view of the people on your site as "customers" has the strong connotation that direct monetization is occurring, and that usually happens on ecommerce properties. I think this implies both the highest value and best treatment of the folks visiting your site.

Interestingly enough, business like social gaming sites would be wise to use this type of terminology when they depend on virtual goods models. Social gaming properties are not much unlike ecommerce sites, and it would be wise to have the same focus on merchandising, having attractive shops, cross-selling and up-selling, as well as treating your customers like they will hand you money.

Users

At the heart of "users" is the idea of using a product, or utility, or other functionality-focused usage. At least in my world, this is the most common terminology I hear. On the plus side, it creates plenty of opportunties for discussion around featuresets and product-oriented business strategies. However, on the downside, it doesn't explicitly acknowledge the nature of the advertising business as "audience" does, nor the imply the treatment that calling them customers would.

For my projects, I am particularly interested in virtual goods models for monetization, and as a result, it seems wise to reserve the word "customer" to refer to the people we attract.

Any other labels I'm missing? Comments and suggestions welcome.

Data portability: Is the social network data you’re hoarding treasure or trash?

I recently wrote a guest blog yesterday at InsideFacebook.com, and wanted to republish it here as well.

Data portability: What's the value of your social network data?

This blog post will be focused on the business-perspective of how a

company operating one of these social networks might think about their

data, particularly in regards to advertising monetization.

There's been a lot of discussion on the data portability issue in one form or the other. The consumer perspective on the data portability issue on the consumer side has been well-covered, and is well represented by Robert Scoble, Marc Canter, Gillmor Gang, and others. This is a big topic, especially when you've added as many friends

to Facebook as our Doonsberry friends have, in the above comic.

Business reasons to resist portability

When a company has aggregated a critical mass of audience and data, it's clear that data is worth something, but unclear how much. In particular, one might be resistant to data portability for a number of reasons, including:

- If the data can be monetized for through advertising means, then a company might want to have proprietary access to that data

- If a competitor can easily import user data, it makes it easier to switch services

- If a user can too-easily share their data with external services, it may create privacy and security issues

- … and others

There are many other reasons why businesses are reluctant to jump full bore into releasing control of the data, some great for consumers, some neutral, and some completely unaligned with their users. It's my opinion that, like the way Windows has evolved, you want to provide access but need to make it very clear what they are getting themselves into.

The reason why spyware has turned into such a huge industry was that for many years, it was far too easy to install any executable off the internet – and the Operating System gave poor warning on what users were trying to do. There are things you want to do to make sure you're not destroying an entire ecosystem, while still supporting the goals of your users.

My particular interest in this question mostly has to do with the value

of the data, particularly from an advertising standpoint – the first

bullet above.

The monetization of user data

The question is, if companies are busy hoarding all this user data – what is it really worth? How do you evaluate its value? And how does it fit into the context of the overall advertising market?

To outline the answers to this question, I'll cover a couple specific topics:

- Ad network business models

- Interest versus intent

- Data to traffic overlap

Then I'll conclude with a short discussion on the future of social network data.

Ad network business models

The market for user data is very early. Only in

the last few years have companies emerged like Revenue Science, Tacoda,

Blue Lithium, and other companies you see on this list.

Note, of course, that I was previously employed by Revenue Science and

worked on their direct response ad network (in addition to other roles).

But to step back: For newbies to the advertising world, it's important to note that there are many many ad networks out there besides Google AdSense. For example, Blue Lithium, Valueclick, ContextWeb, Advertising.com, etc are all ad networks that fundamentally do the same thing:

Buy ad space at a lower price, then resell it for a higher price

Quite simply, it's arbitrage. So they sign up publishers, get them to stick ad code on their pages, and then fill the space with banner ads, Punch-the-monkey flash games, etc. The bigger the delta between what the buy it for and what they sell it for, the better their profit margins.

The problem is, there's like 300 ad networks out there, and it's getting more competitive every day. So like a Wall Street bank, these ad networks have to get smarter (and bigger!). They allow advertisers to target on context, geography, time, demographics, and many other factors. They support Flash ads, text ads, video ads, banner ads, all in many different sizes.

In all the targeting, they become huge consumers of data. To competitively identify low-value ad inventory and buy it on the cheap, you need to have more data than:

- the publisher you're buying it from

- the 299 ad networks who are also looking for the low-value inventory

If you have less data than either, then the ad inventory price will get bid up, and all of a sudden it'll be hard to get the volume of traffic you want. And thus, it makes sense to voraciously gather and utilize all the data you can, across many different areas. In particular, "user data" is interesting – if you can tell when someone in the market for a car, ad impressions against that user are suddenly very valuable.

Question is: What kind of data is valuable? And what kind is not?

Interest versus Intent

The first step to understanding the value of data is to look at the marketing funnel below:

You can consider the top part as consumer interest whereas the bottom part is consumer intent.

A user moves through a long funnel before coming into market and exhibiting buying signals (aka Intent). And there are a lot more people at the top, who are sorta kinda maybe in the market for a car (but maybe don't even know that they are) versus the folks at the bottom of the funnel who are ready to get their car loan processed and drive out to dealerships the next weekend.

When you are the bottom of the funnel, you are part of a select group, and because you are very close to taking action, it's easy to value you as a user. Here's how a car dealership might figure that out:

- The dealership closes roughly 1% of anyone coming through as a "lead"

- They make on average $2000 per car they sell

- So they are willing to buy a lead for $20

- Then build in some margin, and they're willing to spend $10 on a lead

(Note: these are made up numbers)

The problem here, however, is that there are only so many people ready to buy at one time. So typically, all this inventory gets sold out, and then you have to move upstream to buy more users. In particular, there's often a big concern that a product can get left out of the "consideration set" if it's not branded well. That is, even if you're buying all the Ford dealership leads as you can, if you can't position your gas guzzling SUV for the eco-conscious set, they never get the chance to filter to the bottom.

When you're at the top of the funnel, it's hard to value the ROI from advertising to those users. The focus there is to just be in the game and inside the "consideration set," as I mentioned. So the targeting there isn't typically focused on in-market status, but rather on more qualitative things like:

- demographics

- psychographics

- desirable editorial areas (to complement the values of your brand)

- really cool ad creative

- etc.

Anyway, it's not as quantitative, and the distance between the brand side and revenue is often larger than folks want it to be. But it works, even through the following classic advertising quote applies:

"Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don't know which half"

— John Wanamaker

As a result, it may not surprise you that data around in-market behaviors (aka Intent) are worth a LOT more than the more watered down stuff (aka Interest), particularly because you can prove to advertisers that the former will make them money.

For search engines, the ultimate collector of consumer intent, you can get 1000X+ times the monetization levels that you'd get from social networks. Social networks, being communication-oriented, have very little intent relative to other sites on the internet. This doesn't mean the social network data is worthless, but it's definitely hard to use it to monetize.

Where are other places you can find intent?

- Comparison shopping sites

- Product reviews

- Loan calculators

- Shopping sites

- Search engine marketing landing pages

- etc.

Think of any service you might go to in order to make a transaction, or prior to making a transaction. The more of that data you have, the better off you are.

On the flip side, this data is scarce. The bottom of the funnel doesn't have many people, and because people aren't typically shopping forever on a product, it means the data is perishable.

Data to traffic overlap

Once you have the data, you have to figure out how to use it to buy-low and sell-high. One of the big questions revolves around when/where your data is applicable – and this problem is sometimes referred to as "overlap."

Let's say that you collect data about a bunch of unique users on your site, and all those users are very valuable. Then you want to find those same users on some other site, which has cheapo inventory. The plan is that if you can buy that inventory for cheap, but you can figure out the good stuff in there, then you can buy just the good stuff. Sounds great right?

Problem is, what's the overlap of users between your site and this publisher's? If it's small, then you might not be able to write a big check to justify the expense of doing the transaction. If you have 100k users and then you're finding some % of that on some other site, then that's not so exciting. So you really need to aggregate a ton of data to make this transaction work. And ideally, you are able to use your own data, but also use the data of other similar ocmpanies – this allows for more opportunities to bring in new users, rather than just recycling the current set of users you already have.

This issue of insufficient overlap has been alleviated somewhat recently. Since the mid 00s, there's been a number of ad networks that allow you to buy advertising by-the-cookie. Right Media, in particular, leads in these types of transactions. But Valueclick, Ad.com, etc all can provide similar arrangements as well. So given that these ad networks have already pre-aggregated a huge amount of inventory (several hundred billion pageviews per month), you can get reasonable scale on your data even if you don't have too much data. The downside to this, of course, is that it introduces yet another middleman into the mix, and since they know you are buying by-the-cookie, it's easy for them to charge you a little extra. Doh.

Conclusion

So to summarize the article above:

- One potential issue that makes social networks resist data portability is the monetizability of the data

- Not all user data is created equal, there's interest versus intent

- Social networks generally produce lots of low-value interest data, which has weak ROI attached to it

- Search engines, review sites, comparison shopping, etc all produce high-value intent data

- Even if you have the data, you have to worry about whether or not you have enough of it to matter – although ad networks and exchanges have started to alleviate that

Questions and comments welcome!

Social gaming and MMOGs: Quick link roundup

A friend of mine recently asked me for a list of blogs, books, and other resources on game design, social gaming, virtual goods, etc. I wrote up a quick e-mail, and thought I’d publish it here as well.

If anyone has interesting stuff to add, please shoot me a note at voodoo [at] gmail!

I have not found much on the metrics of the games industry, particularly on the virtual economies side. That’s definitely one area I’d like to learn more about…

MMOG and virtual world blogs:

- Virtual World News

- Massively

- Terra Nova

- Virtual Economics

- Virtual Economy

- Free to Play

- PlayOn from PARC

- Worlds in Motion

- Jeremy Liew (Lightspeed)

- Dan Cook (Seattle game designer)

- Daniel James (CEO of Three Rings – Puzzle Pirates & Whirled)

- Sean Ryan (CEO of Meez)

- Nabeel Hyatt (CEO of Conduit Labs)

- Erik Bethke (CEO of GoPets)

- Nick Yee (Stanford researcher on virtual worlds)

- Justin Smith (Inside Social Games)

- Damion Schubert (MMOG designer)

- Designing Virtual Worlds (New Riders Games)

- Play Money: Or, How I Quit My Day Job and Made Millions Trading Virtual Loot

- Massively Multiplayer Game Development (Game Development Series)

- Game Design Workshop: Designing, Prototyping, and Playtesting Games (Gama Network Series) (Gama Network Series)

UPDATE: added a couple new links. There’s more on Mike Gowen’s blog here.

User retention: Why depending on notification-driven retention sucks

- They love your site so much that they come back themselves (direct-navigation)

- They see or get a link from a friend or a source while they are browsing (reacquisition)

- You send them a notification, like a friend-add, a newsletter, a list of top videos, or similar

The case where the user navigates to your domain to come back is great. It means that you've built a brand that people can recall from their memories, and they like it enough that they will automatically come back. In general, this seems like the most desirable scenario.

- Good friend sends you a private message

- Friend writes on your profile

- Acquaintance writes on your profile

- Friend sends you a friend request

… versus less desirable messaging, which lacks personal context and comes from the company, not a friend or :

- "Come try out new feature X!"

- "Check out this week's top videos!"

- "You should update your photo!"

- Total stranger sends you a friend request

In the cases where you are getting notifications from just the site, it's far more likely users will think of it as spam, which is obviously a negative. The more personal information that is in the notifications, and the more personally relevant that information is, the better.

- Initial active users = 1000

- % that will create useful news = 10%

- % that will click through on the notification: 5%

- The idea is that you have 1000 users, of which 10% will create useful news

- That means 100 people will create news

- As long as there's at least 1 piece of news, that news can be republished to 1000 people as 1000 notifications (Note that in a more sophisticated model, the more news items, the better the clickthrough rates, and the less, the smaller the CTR)

- Once you have 1000 notifications out there, then there's 50 people that click through

- Of those 50 people, they produce 5 pieces of news

- That 5 pieces of news is then republished again to the 1000 people

- Then the secondary cycle repeats again

Basically, there's a quick collapse from 1000 active users down to 50 active users. If you made the model more complex, and added a CTR that goes down depending on how much news there is, or adding deliverability issues from people getting too much e-mail, then you could see this spiraling down to 0 actives.

- Build features that support high-quality single-user experiences

- Make it easy to create content on the site, and reward users that do

- Create differentiated experiences that users can weave into their daily routine

- Be as sticky as possible – this is a place where software clients are great, but websites are hard

What’s the value of a user on your site? Why it’s hard to calculate lifetime value for social network audiences

Who is this, and where can I find more pics??

For those of you who aren’t familiar, the photo above is of Christine Dolce, aka Forbidden, who is a famous MySpace celebrity (and will surely get her chance to star in a VH1 reality TV show). I can hear a rush of clicks googling her for pictures, so I’ll just provide you the link to her MySpace profile here. Let’s get back to Forbidden in a second, since she fits into a larger discussion.

LTV and the goal of infinite segmentation

The core of many marketing programs is segmentation – you take your core audience, identify differences between their motivations, spending patterns, and behaviors, and tailor your messaging to hit that audience. The better defined your segments are, and the more granular they are, the more opportunities you have to personalize your message when you reach out to them.

One way to do this segmentation is to look at "Lifetime Value" (LTV). Calculating lifetime value (LTV) of your customers is a great way to understand how they fit into the core of your business. Typically, your best customers will represent a significant amount of revenue, and you want to make sure they’re happy. Having a granular LTV calculation where you plug in a user’s historical data allows you to come up with infinite segmentation in terms of how you want to differentiate the experience high-value customers get versus low-value ones.

LTV for retail sites versus social sites

For retail sites, the calculation of LTV is pretty clear. In plain English, you might define it as:

The stream of all previous and future profits that a user generates from their purchases

So for a given user, you’d add up all their previous transactions and then add that to whatever model you’ve created about their likely future transactions. Part of what makes this work is that:

- Transactions in a retail setting are unambiguous

- Each individual makes an isolated impact on the system, in the form of a transaction

- Retail buying has a long established history of data, both online and offline

Now let’s look at social properties, particularly ones that have the characteristics that they are ad-supported, are heavily based on UGC content, and incorporate viral marketing. If you were *just* to consider the advertising portion, then it might be easy – the LTV of a user would be defined as:

The stream of all previous and future ad impressions that a user generates from their usage

So that seems pretty clear – if you’re a user who generates 100 ad impressions a day, you are worth more than someone who generates 10.

The problem is when you try to incorporate the value of the UGC that a user generates, or the users they help acquire (or retain!) as part of the LTV calculation. And for this discussion, let’s go back to talking about Forbidden.

Forbidden as an LTV outlier

The problem with a user like Forbidden, and possibly even more so Tila Tequila, is that only a small amount of value that they create comes from their actual usage of the site. Instead, they provide additional value through user acquisition, retention, and content creation that is poorly measured by the definition above.

Another way to think of this is that if you were to remove these users from MySpace, you would not simply be subtracting their LTV from your overall site’s value. In fact, it would be an outsized decrease in value, since users like Forbidden and Tila Tequila bring many millions users onto MySpace, and entertain millions of people, keeping them on the site.

A couple commenters of my LTV in casinos blog post said as much:

Social network death spiral: How Metcalfe’s Law can work against you

Metcalfe’s Law

Does everyone remember Metcalfe’s Law? It was formulated by Bob Metcalfe, the inventor of Ethernet and co-founder of 3Com, who stated:

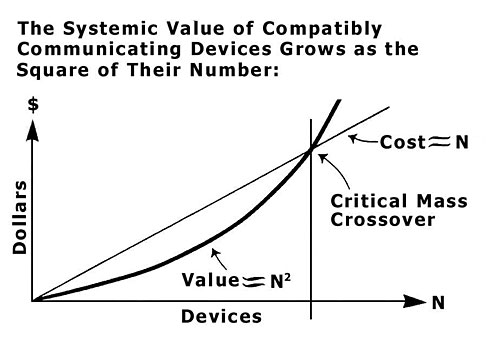

The value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users of the system (n²).

For those that are interested in the math behind it, basically the idea is that if every new node in the network connects with every pre-existing node, then as you gain nodes, you non-linearly increase the number of connections that everyone has with everyone else.

That’s pretty neat, and for the social networking folks who are aggregating large audiences and treating their businesses like communication utilities, it’s both logical and helpful to think that these social communities abide by network effects like Metcalfe’s Law. In fact, it’s a DIRECT reason why these networks want to get as big as possible, and have a social graph that’s as comprehensive as possible, and why they should ultimately be opposed to Data Portability. And I think we’ll see these players’ strategies ultimately reflect these strategies.

But Metcalfe’s Law can also affect social app creators. Let’s discuss how this might play out for folks who are building apps on social platforms, rather than operating the social platforms themselves:

“Jumping the shark” and Metcalfe’s Law

In a previous post, I wrote a bunch about how dangerous (and easy) it is to jump the shark in an enclosed space like the Facebook Platform.

Here’s the good scenario:

Let’s say that you retain users well, and you don’t get a sharkfin graph on your traffic. In that case, if you combine the two ideas – Metcalfe’s Law and with the viral loops on the social platforms – you can imagine that in the success case, you are creating N^2 value with very large N.

For folks building application on Facebook, Opensocial, etc., it’s nice to think that your new app is gaining value much faster than if you built your own

destination site. This allows you to get the N^2 benefits of Metcalfe’s Law without incurring significant costs of acquisition as you scale N up to a large number. This the best of both worlds.

Here’s the bad scenario:

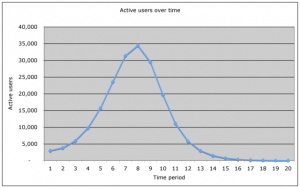

Let’s consider the other case, where your app’s retention sucks, and you are going through the sharkfin graph of rapidly acquiring users, hitting a peak, and then falling down:

(scroll past the image for more)

Now all of a sudden, Metcalfe’s Law works against you – for this, I will introduce the corollary, Eflactem’s Law.

Eflactem’s Law

Funny enough, everyone always talks about Metcalfe’s Law like it’s a good thing, and they say that because they assume that N is increasing! But let’s consider the opposite: If Metcalfe’s Law says that your network grows value competed by N^2, then Eflactem’s Law states the reverse. It says:

As you lose users, the value of your network is decreases exponentially (doh!)

That is:

- If you have 100 users, and then grow to 200 users, your “value” has increased from 10k to 40k.

- But if you START with 200 users, and end up with 100, then you are going from 40k in value to 10k in value.

And that sucks. Perhaps this should be called Murphy’s Law instead?

In fact, you see this happen all the time at dinner parties or events. Things are great until one or two people announce the intention to leave. If those folks are fun and entertaining, there’s an immediate realization that the quality of the experience is about to go down. And yet more people announce their intention to leave, and so on, until you are left with the party hosts and a big mess ;-)

Advanced discussion: Social Network Death Spiral

Now let’s do a more advanced discussion using the concepts above – for some new readers, this discussion might completely be incoherent ;-)

Let’s consider a specific scenario where a social network could easily start to “Death Spiral” – here’s some set up on the scenario:

- You have a bunch of users, let’s call the total number N

- The total number of users in the ecosystem, called the carrying capacity, is variable C

- These users all individually require some utility value on a site, let’s call this V_required

- Then there’s a retention %, called R, which depends on two factors:

- If the utility value for users is satisfied, that is, V > V_required, then R close to 100%

- If the utility value drops under V_required, then R is crappy, closer to 0%

- And to borrow Metcalfe’s Law, the value of the network is calculated at V = N^2

So the scenario is that as the total users for the application reaches the carrying capacity, you basically hit a point of maximum saturation – this is defined by the ratio N/C. Sometimes this ratio can also be referred to as the “efficiency” of a user acquisition process, which relays how many people you actually acquire versus the universe of all users. (Obviously you want this to be as large as possible)

Once you hit the carrying capacity and acquire all possible users, N is at the highest point, and thus the network value is also at its highest point, V = N_max^2. Similarly, because the network value V is at its highest, the retention reaches its highest point as well.

The question in this scenario is, at any point during the growth of the network, does the network value V exceed the required value of the site, which we call V_required? Does the network break through the critical mass of value?

If so, retention should be great, as defined by the explanation above. In fact, maybe you reach V_required early on during the growth of the site, which makes the acquisition process much more efficient. Early on, maybe the userbase wasn’t sticking, but a critical mass threshold is met, and suddenly the entire userbase sticks, which creates a long-term creation of ad impressions and company value.

However, if you don’t reach the required value in the network, then you’re pretty much screwed. Then the retention sucks, since the users aren’t finding value, and some percentage of them will leave. This will then remove more value from the system, causing yet another round of users to leave. This continual loss of users is a death spiral that collapses your network in fine Eflactem’s Law style.

A very interesting variation of this is when you apply Metcalfe’s Law not to the entire network of users, but rather think of a social network as a loosely grouped set of connections. In that case, some local networks might have achieved critical mass, and if they are big enough, they will be retained. However, if the smaller networks around any given group start collapsing, then sometimes even the large networks will get pulled down with them.

Conclusion

To summarize this post:

- Gaining users is great, but preventing the loss of users is also very important

- Creating a sharkfin graph on your traffic means exponential descruction of value

- Critical mass plus network effects implies that complete collapse of networks is possible too

As always, comments and questions are welcome.

GigaOm’s “10 Blogs We Love” and 15 Blogs that I love!